China’s transgender people too scared to come out like Elliot Page – ‘You become a freak’

- Many applauded Page’s courage after the Canadian actor came out as trans in December, but for China’s transgenders the reaction is usually much more hostile

- Many suffer domestic violence, bullying, job discrimination and ‘conversion therapy’, but NGOs and activists are pushing back one small step at a time

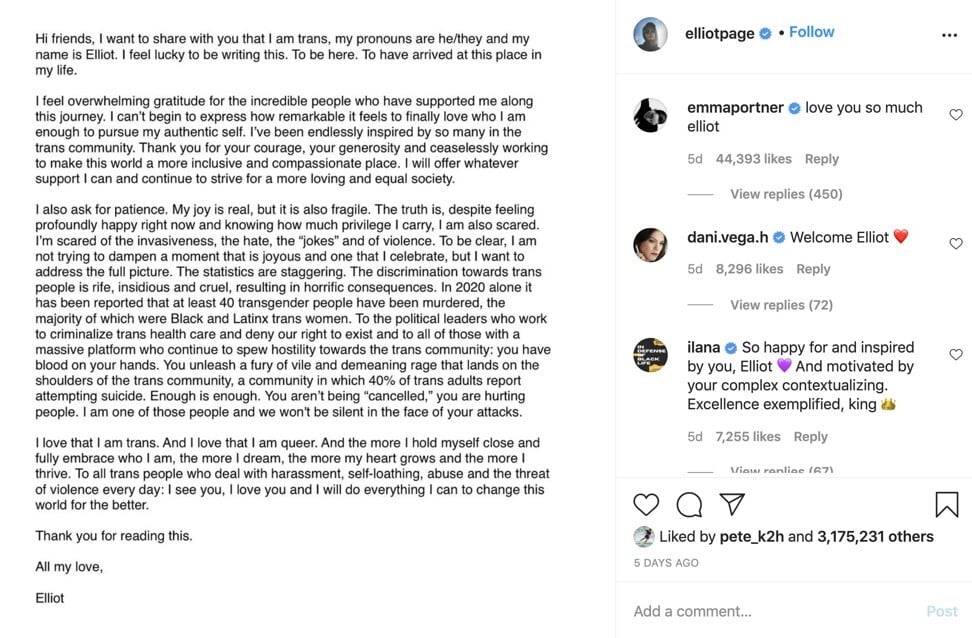

When Juno star Elliot Page, known as Ellen Page until December, came out as transgender, his social media pages were instantly filled with blessings and love from actors, musicians and other celebrities.

“I feel lucky to be writing this. To be here. To have arrived at this place in my life.”

Many applauded his courage and said they looked forward to his coming work. In China, however, coming out as transgender is a much more arduous path.

One of the most famous and outspoken transgender figures in the country is Jin Xing, a former dancer and now talk show host. She had wanted to be a woman as early as six and had her sex reassignment surgery in 1995, aged 28.

Known for her witty and sarcastic comments on social issues, Jin had been one of China’s top dancers until she became a talk show host in the later stages of her career. Even at her level, Jin encountered discrimination.

‘Why can’t men wear pink?’ The designer behind the Amesh label

In 2011, she was banned from being a judge on a talent show on television channel Zhejiang TV. She claimed on China’s Twitter-like Weibo service that the ban came from the provincial government because of her gender transition. Authorities never publicly responded on the issue.

At the grass roots level, the transgender community has a much harder time. The obstacles they face are more day-to-day and they have fewer resources than Jin to stand up against it.

The biggest problem is domestic violence as parents refuse to accept their transgender children. That’s according to the director of the China Sogie Youth Network, a Beijing-based NGO, who goes by the alias Xiaomi.

A report from the Beijing LGBT Centre in 2017 found that of 1,640 respondents, all but six had experienced domestic violence at the hands of parents or guardians after coming out. The violence included beating, confinement, financial restrictions, sending the children for “conversion therapy” or kicking them out of home.

Other difficulties they face include bullying at school or university, employment discrimination, medical discrimination, and overall government policies, Xiaomi said.

Transgender people have a hard time succeeding in job interviews, can only get reassignment surgery after being diagnosed in hospital as having “gender identity disorder”, and can only change the gender on their ID cards after their surgery, Xiaomi said.

Chao told how she had first attempted to enter a men’s bathroom but was stopped by a janitor because she was wearing a dress. She then tried to go into a women’s room, but a security guard asked to see her ID; when seeing that it stated “male”, he called her a “pervert”.

Since then, Chao has spoken extensively in public to highlight the issues the trans community faces. In 2016, she appeared on the popular Chinese debate show Qipa Shuo to share her experiences.

“Many in the community feel anxious,” Chao told the Post. “Many can’t take the mental pressure, become depressed and even choose suicide.”

She said people like Jin, who are in a higher social class, can prove their value and nobody can easily take them down. But for many others, they have to hide their gender from the public to avoid malicious attacks.

After Page’s statement, we compare the situation we are in. It feels like a world of difference

In the face of widespread discrimination, NGOs and activists have pushed for change through lawsuits and the development of studies highlighting difficulties the community faces, Xiaomi said. Among past high-profile cases is one of Mr C, who was involved in the first transgender labour-dispute case in China.

In 2015, Mr C, a transgender man, was fired from the Guiyang Ciming medical exam centre in southwest China because “he liked wearing male attire” and his image was “not in line with company requirement”.

The result may not have been entirely satisfactory, but the community is pushing back one small step at a time. They have also formed an online community where members watch closely for domestic violence cases on social media and send rescue missions.

Other efforts to help transgender people in China have included establishing a hotline to respond to medical and psychological needs, as well as provide support, Xiaomi said.

Chao said the reality is that Chinese society still embraces two-dimensional gender views rather than a more diverse one, and there remains a lack of education. For transgender people, and those whose gender is non-binary, “you become a freak” – you need to be treated, otherwise you would encounter problems and cannot blend into society, she said.

“After Page’s statement, we compare the situation we are in,” she said. “It feels like a world of difference.”

.jpg?itok=H5_PTCSf&v=1700020945)