- A day after vlogger Lhamo’s death, President Xi Jinping told a UN conference his country was committed to eliminating discrimination and violence against women

- But Lhamo’s case, and other recent cases of women killed by their partners, show how far China still has to go to meet that goal

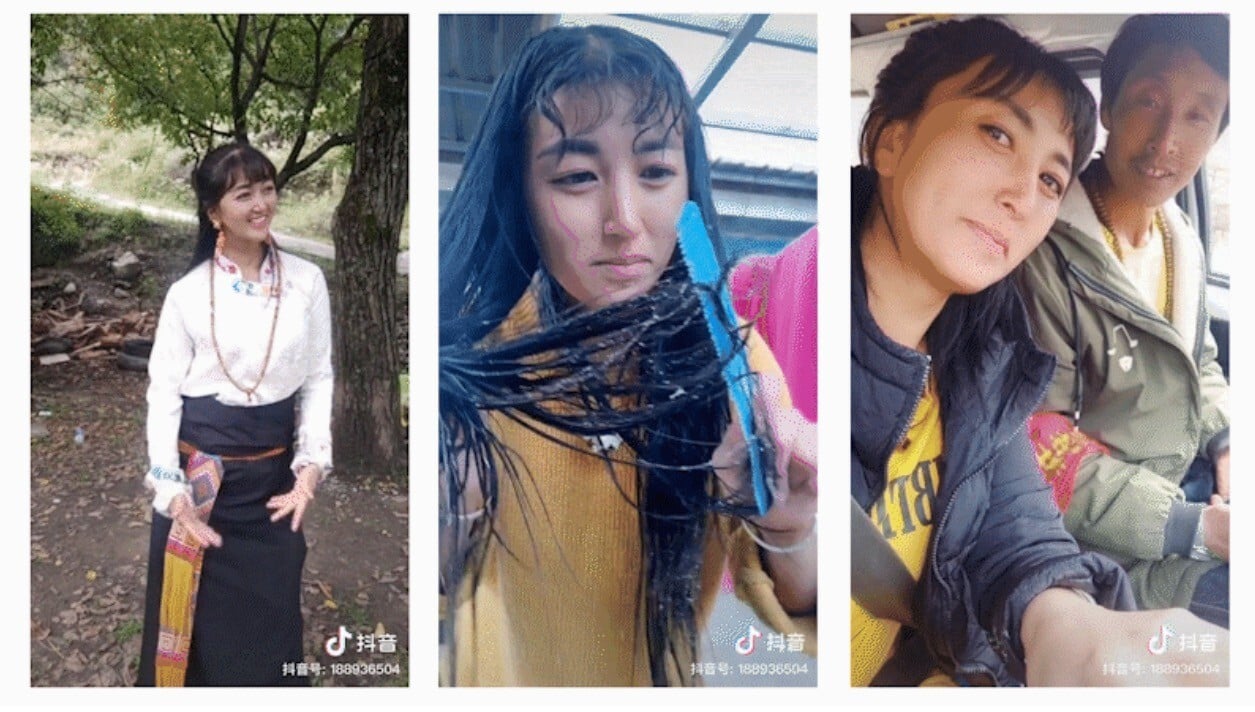

Despite a rising awareness in China of domestic abuse and legislation to protect victims, the recent brutal killing of Lhamo, a Tibetan woman who ran a video blog, by her ex-husband has highlighted the country’s struggle to curb deadly violence against women.

The Chinese government says it stands firmly by gender equality and the protection of women against discrimination and violence. The day after Lhamo’s death, President Xi Jinping told a United Nations conference that China was committed to eliminating discrimination and violence against women.

But Lhamo’s case, and many other recent reports of women killed by their partners, show the goal is still far from reality.

Lhamo’s death dominated Chinese social media for days. “I hope he gets sentenced to death,” read a comment on microblogging platform Weibo, echoing calls by state media for harsh punishment for Tang.

As details of the circumstances surrounding Lhamo’s death trickled out, it became clear the killer’s hostility alone could not fully account for the tragedy. An examination of the events leading up to the attack has revealed a disturbing pattern of institutional failure.

To protect its abused women, China must fight ingrained male chauvinism

According to the United Nations’ annual global homicide study, women are more likely than men to be victims of intimate partner killings. Among 87,000 recorded deaths of women and girls resulting from intentional homicide worldwide in 2017, 34 per cent were killed by their partners.

China has no official data on intimate partner killings. An examination of public court records shows that in September and October 2020, at least 87 people were convicted of murdering or attempting to murder their current or former partners, of which 73 were men and 14 women. The World Health Organisation estimated in 2016 that 30 per cent of women globally suffered physical abuse from their partners at some point in their life. The median estimate for China was 38 per cent.

In one video post, she explained in the caption why her hands were cracked and dirty. “I have the face of a 30-year-old but the hands of a 50-year-old. Don’t criticise me for the dirty hands. I use my hands to make money.”

When a follower asked: “Did you not wash your hands?”, Lhamo’s reply was blunt. “No water.”

We told them someone could be killed if it continued like this. But they didn’t take it seriously. I don’t know what the police were thinkingDolma, sister of domestic abuse victim Lhamo

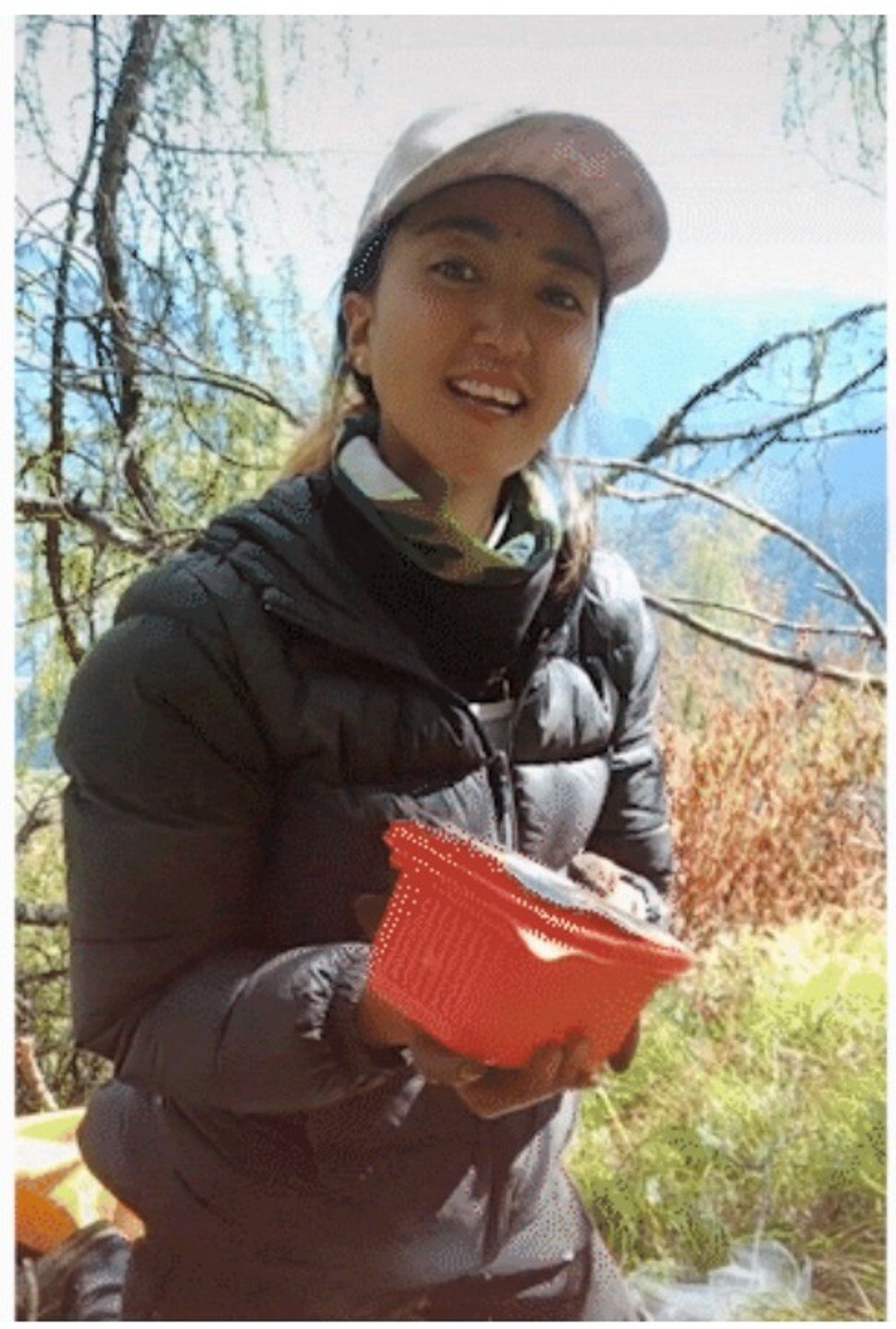

Lhamo’s work reflected a life that revolved around the seasonal harvests of qianghuo, or Notopterygium root, a bitter herb used in Chinese medicine to treat symptoms of a range of diseases.

During qianghuo season, she would spend days at an altitude of 4,300 metres (14,000 feet) with her father, who sometimes appeared in her videos. They lived in makeshift huts in the wild. She cooked noodles, potatoes and tsampa, a cereal-like Tibetan staple made of barley flour.

She was, however, partial to a fast food adored by millions across China. In a video of a herb-picking trip in October, Lhamo showed off a self-heating meal of rice and pork that comes in a box with a chemical mixture that heats up when water is added. It was as luxurious as a big banquet in the city, she said. “I always feel so hungry in the wild.”

In addition to her father, Lhamo’s sister and two sons made occasional appearances in her posts. But one person was notably absent: her husband.

According to Dolma, her sister was 18 when she married Tang, a local Han Chinese resident. He had also dropped out of school and worked a series of casual jobs. Tang’s family ran a teahouse and, after her marriage, Lhamo worked there when she was not picking herbs with her father.

“It is like this over here. We felt it was not good to tell outsiders about our family matters. It was not good for the kids. So we never told others about it.”

Dolma tried to talk Tang into stopping the violence, without success. According to Dolma, Tang hit Lhamo and dislocated her arm after he lost an online poker game one evening in March, when everyone was home because of the coronavirus.

The next day, Lhamo sought and was later granted a divorce – but she remarried Tang after he threatened to kill their sons. He also knelt before Lhamo in remorse, promising never to beat her again, Dolma said.

The violence did not stop. Dolma said Lhamo called the police at least twice after the March attack, but each time they refused to intervene. “The police said it was our family matter and didn’t do anything about it. They came to take a look and left.”

Is Hong Kong losing the fight against domestic violence?

In May, Lhamo filed for divorce again and sought refuge with relatives while she waited for a ruling. It was during this time that Tang, looking for his wife, entered the shop where Dolma worked and punched her, fracturing bones in her face. She was treated in hospital, while Tang was called briefly into the police station but walked out a free man.

“Our relatives went to the police station, and asked officers to do something about this man,” Dolma said. “We told them someone could be killed if it continued like this. But they didn’t take it seriously. I don’t know what the police were thinking.”

Lhamo rejected the court’s offer of mediation services and, on June 23 – more than a month after she sued for divorce – she was granted one. The judges gave custody of her two sons, then aged 12 and two, to their father.

Lhamo posted her last Douyin video in September. It was after 8pm, and Lhamo was doing a live stream in the kitchen when Tang arrived. Lhamo’s father and brother-in-law, asleep in another room, were woken by Lhamo’s screams for help and found her doused in liquid in the kitchen. As they ran for help and to call the police, the house caught fire, Dolma said; this was followed by an explosion. Lhamo was rushed to hospital with burns to 90 per cent of her body and fell into a coma.

Later that night, Tang was arrested on suspicion of murder, according to a statement issued by the Jinchuan County Public Security Bureau. He had burns to 45 per cent of his body, according to Chinese news outlet Guyu. An officer at the public security bureau declined to answer questions about Tang’s case or Lhamo’s previous reports of domestic violence.

Dolma said her sister’s life could have been spared if the police had acted differently. “They could have given him a warning,” she said. “Not to mention detention.” Dolma and her father have been staying at a temple during Lhamo’s funeral, which lasts 49 days in Tibetan Buddhist custom. “If they could just educate him, the situation would not be like this,” Dolma said.

Police officers think fights between couples are family matters, not their businessHope, a volunteer assisting victims of domestic violence

Kim Lee, perhaps China’s most famous survivor of domestic violence, went through a similar ordeal to Lhamo when she sought help in Beijing in 2011.

Lee had a bleeding ear, swollen nose and bumps on her forehead; she told police the violence had been inflicted by her then-celebrity husband Li Yang, founder of the popular Crazy English language teaching programme. She recalled that a female officer, upon learning her husband’s identity, told her: “He is a good person. You are also good.”

When Lee asked the police to make a record of her injuries, she said they replied: “But he is your husband.”

At a time when domestic abuse was seldom discussed in public, Lee’s criticisms of her ex-husband and of China’s law enforcement made her both a voice and an inspiration for many Chinese women who were suffering in silence.

In 2016, China enacted a law against domestic violence law that explicitly bans physical and psychological abuse at home. Police are required to investigate, collect evidence and help victims.

Why domestic violence is as barbaric now as it was in ancient China

Feminists cheered the legislation as a victory and an important step forward in protecting China’s 682 million women. For Lee, it was a relief, at least providing women “a rope to cling to” when they needed help.

“All anyone ever associates me with, asks for my opinion about or even knows about me is that my husband beat me and I publicly spoke out about it. I was just exasperated,” she said. “The fight to eliminate it should not have to rest on any survivor’s shoulders.”

In America, a lot of women take it for granted how much freedom they have to protest, go to the street, to counteract. It is so much harder in ChinaKim Lee, survivor of domestic violence

Activists and survivors have expressed shared pain while reflecting on a patriarchal culture that exerts a strong influence, both in the domestic sphere and within law enforcement. A volunteer, who has been assisting victims of domestic violence for five years, said some police officers she met had never even heard of the 2016 anti-domestic-violence law.

“[Police officers] think fights between couples are family matters, not their business,” said the volunteer, who is based in Xian in northwest China and prefers to be identified by her English name, Hope. “Even when the couple fight in front of them, they will pull them apart instead of making it a criminal case.”

Some have called Lhamo a “perfect victim”. She was financially independent and had tried time and again to seek help and escape from her abusive marriage. Her experience has led many Chinese women to conclude that the abuse that is so prevalent is caused, not so much by victims’ reluctance to speak up, as by the refusal of institutions to offer help.

Lhamo’s death devastated Lee. She said Lhamo’s case made her realise that having laws in place was far from enough – the belief that domestic violence should be dealt with inside a household had persisted and often prevailed over the law.

Lee said she regretted writing about forgiving her own ex-husband, because it could be used in a disingenuous way and fed into the old narrative that officials should stay out of couples’ fights.

“I am starting to believe that culture is still stronger than the law because in rural areas and other places where knowledge of the law is not that high, officers, the police, even doctors still have the attitude, ‘Yes, this is a family matter’,” she said. “In America, a lot of women take it for granted how much freedom they have to protest, go to the street, to counteract. It is so much harder in China … every step forward takes so much more effort than … it does somewhere else.”

Domestic violence in spotlight in attack caught on camera in China

Women in China are increasingly willing to push back against the state when they feel their rights are being infringed. But these online protests rarely lead to changes offline.

One of the most opposed laws requires a 30-day “cooling off period” for couples applying to divorce. Feminist advocates say this will make it harder for domestic violence victims to end an abusive marriage. Officials argue the wait will reduce “impulsive” divorces, and protect the stability of marriages and families. Despite backlash, the law will take effect in 2021.

Lhamo’s death sparked renewed calls for reforms. A Weibo post calling for a #LhamoBill to protect women from similar violence was shared more than 211,000 times. But the hashtag, along with several others relating to the Tibetan woman, was soon censored.

Kai Lin, an assistant professor of criminal justice with California State University, Sacramento, who has studied the handling of domestic violence by police in China, said the Chinese state was committed to preserving “family harmony” to maintain social stability, even if it sometimes infringed on women’s rights.

This attitude would be hard to sustain, Lin said. As China’s economy continues growing, women are asking for more protection of their freedom and security, he said. His research shows police in urban areas are more likely to intervene in domestic violence cases, possibly because of public interest and pressure.

“The imperative to hold on to family harmony is simply unrealistic, and will become increasingly unrealistic for China,” Lin said. “Women are becoming more autonomous, and they will demand more.”