‘A lot of tears, and food’: a son reunites with his birth mother in Hong Kong 60 years on, after growing up in the US

- Joel John Roberts, who was born in Hong Kong, was adopted by an American family, and grew up in California

- When he decided to trace his roots in 2016, a DNA test eventually led him to his 80-year-old mother

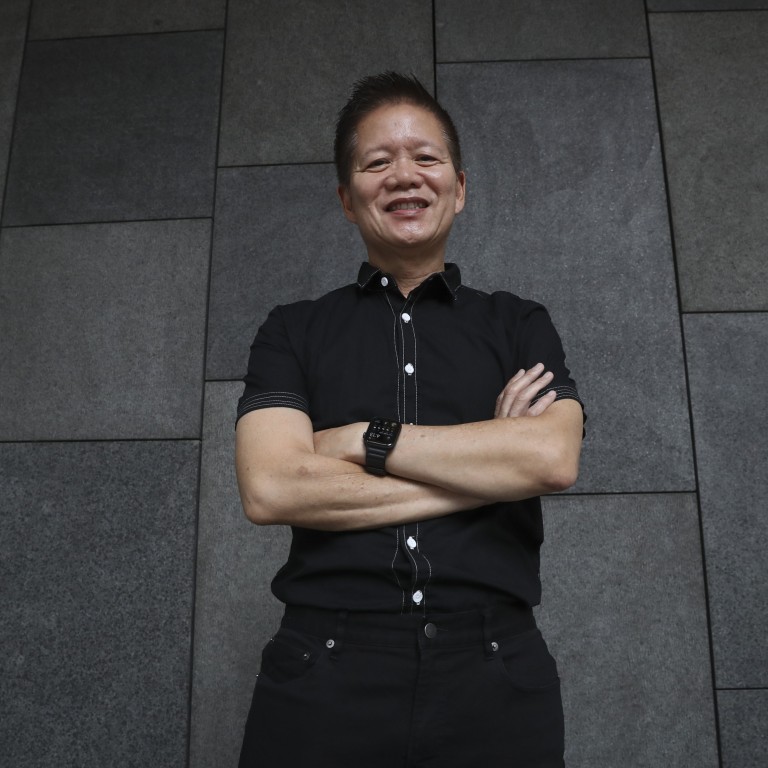

When Joel John Roberts left hotel quarantine in Hong Kong on July 13, he had an important meeting. Roberts, 60, was reuniting with his biological mother, who had given him up when he was two weeks old.

“It’s been an emotional ride,” says Roberts. “There’s been a lot of tears – and a lot of food,” he laughs.

Each day in quarantine, Roberts’ mother, now 80 and who wants to remain anonymous, dropped off food.

Adopted girl, reunited with birth parents on Hangzhou bridge, returns to China

“On day one she delivered a bag full of cookies, pastries, bottles of wine and bread,” he says. “She said ‘I’ve never been able to cook for you or buy you food’ so she wanted to make up for lost time.

All of a sudden I have an uncle in Vancouver, a niece in Singapore and relatives in Australia, Britain, Cyprus ... it’s incredible

“Because I’ve been living in America, she thought I’d love McDonald’s so she delivered a meal – I don’t think I’ve eaten it in 20 years. I’m surprised I haven’t put on loads of weight.”

She also asked him if he wanted her to cook rice with butter, just like his adoptive mother Jean had done for him as a boy growing up in Long Beach, California.

In South Korea, young mothers pressured to give up babies for adoption, documentary shows

“My mum made it each morning because she was worried I would lose connection to my roots.” Jean died in 2015.

“I know she would’ve wanted this day to come,” he says of his reunion with his biological mother. “She would’ve wanted to meet my biological mum, a retired successful businesswoman filled with energy, love, life and entrepreneurial spirit.”

It was 1961 when Robert’s mother, then aged 20 and unmarried, gave him up. “Back then there was a lot of stigma if you were pregnant and unmarried.”

He was put in the temporary care of a couple living in the Kowloon district of Mong Kok. But when his mother did not return to collect him, he was moved to the Fanling Babies Home, an orphanage in the New Territories.

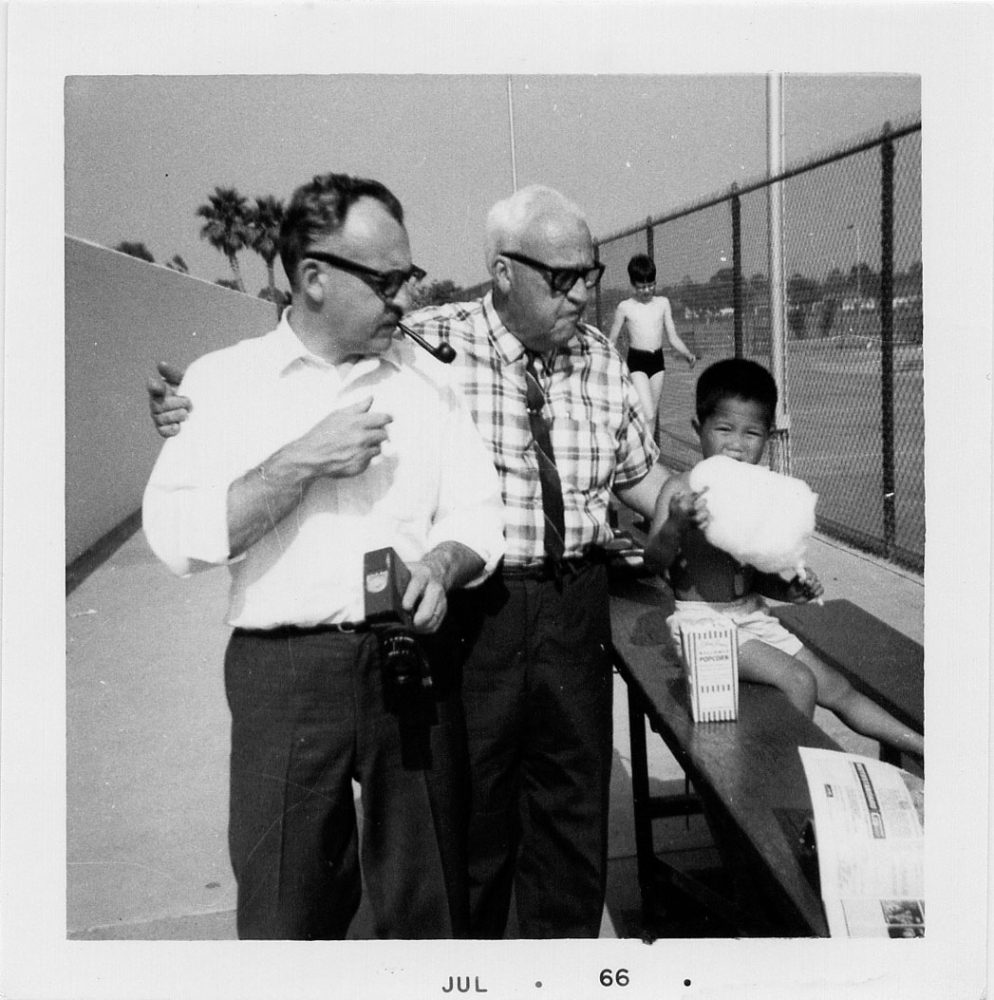

When he was two-and-a-half the Roberts family adopted him. He is one of many children born in Hong Kong in the 1950s and 60s to have been adopted by Western families and taken to countries such as the UK, Canada and the US.

He jetted off to California for a new life with his adoptive parents and four siblings. His father, who has died, was a physics professor fluent in Chinese who was born in Changsha, the capital of central China’s Hunan province.

“Growing up, I always felt special, and my grandfather – a missionary in Hong Kong and China, who retired to California – would always tell me, ‘Joel, we searched all over China to find the perfect boy for us and we found him’.”

Roberts says he grew up knowing there was a “black hole in my life” but was never desperate to look for his biological family.

After college, and aged 21, Roberts returned to Hong Kong to teach English at a Vietnamese refugee camp, one of the many set up to accommodate the more than 213,000 refugees who came to the city between 1975 and 2000.

Sweden to probe adoptions as worries mount over children illegally taken away

“I walked off the plane and into the humidity and lots of strange smells and weird sounds,” he says, adding he volunteered at the camp for six months. “Life in the camp was intense, with barbed wire around it. Once when I was leaving there, I was stopped and asked for my passport because they thought I was a refugee trying to escape.”

In 2016, after reading an article in the South China Morning Post about Hong Kong adoptees returning to the city to find their relatives, Roberts decided to find out more about his identity.

That same year he returned to Hong Kong, but instead of full disclosure from the Social Welfare Department about his parents, he got hundreds of pages with vast amounts of redacted information. The problem stems from the context of the Personal Data (Privacy) Ordinance for adoption which protects parents and adoptees from having their personal information released.

Despite the redactions, some important details were yielded. Roberts’ original name was Frank Brown, or Pak Fat-lan in Chinese, suggesting he was Eurasian and the name was given to him by a Western father.

Roberts doubted this, so he sent a DNA sample to 23andMe, a California-based genetic testing service. The test proved him right – he was 97 per cent Chinese.

But it was his exposure to the site that would open the biggest door to his past. In January 2020, a woman in Hong Kong, who was 4.9 per cent related to him, reached out via the site. “Joel, I think your mother is in my family.” It turned out to be true.

In March last year Roberts was on track to visit Hong Kong to meet his biological mother but the pandemic intensified, scuppering his plans. Instead, he spoke to her on the phone every Sunday. When hotel quarantine in Hong Kong was reduced from three weeks to two, he booked a flight.

Staying mentally and physically fit during quarantine was challenging. He practised yoga, did high-intensity interval training exercises and walked a mile a day in his tiny space. “I packed a skipping rope but my room was too small to use it.” Even mundane tasks such as grinding his favourite coffee beans became an important daily ritual.

Quarantine gave him time to finish his book. “It’s called I’m Home,” he says, tears welling up in his eyes. “It’s about the relationship between my adoption experience and my job working with the homeless.”

For the past 25 years Roberts has run non-profit Path – People Assisting The Homeless.

“We operate in 150 cities across California,” he says. “Part of my story has been that I’ve been homeless (as I never knew my birth home), so this is my way of paying it forward.”

Drifting: Hong Kong’s homeless depicted with compassion

Since arriving in Hong Kong, Roberts’ schedule has revolved around food. “Every lunch and dinner has been booked with family. We had a big dinner two nights ago, I’ve got another big dinner at the China Club tonight. There’s hotpot tomorrow,” says Roberts, who returned to the US on July 20.

He’s also meeting new family members. “All of a sudden I have an uncle in Vancouver, a niece in Singapore and relatives in Australia, Britain, Cyprus ... it’s incredible,” he says.

“I had dinner with a couple of my cousins and they showed me a book of historical records of my biological family that documents 23 generations. It’s amazing.”