The future of watch fairs: why top marques no longer need Baselworld, SIHH, says major Asian collector

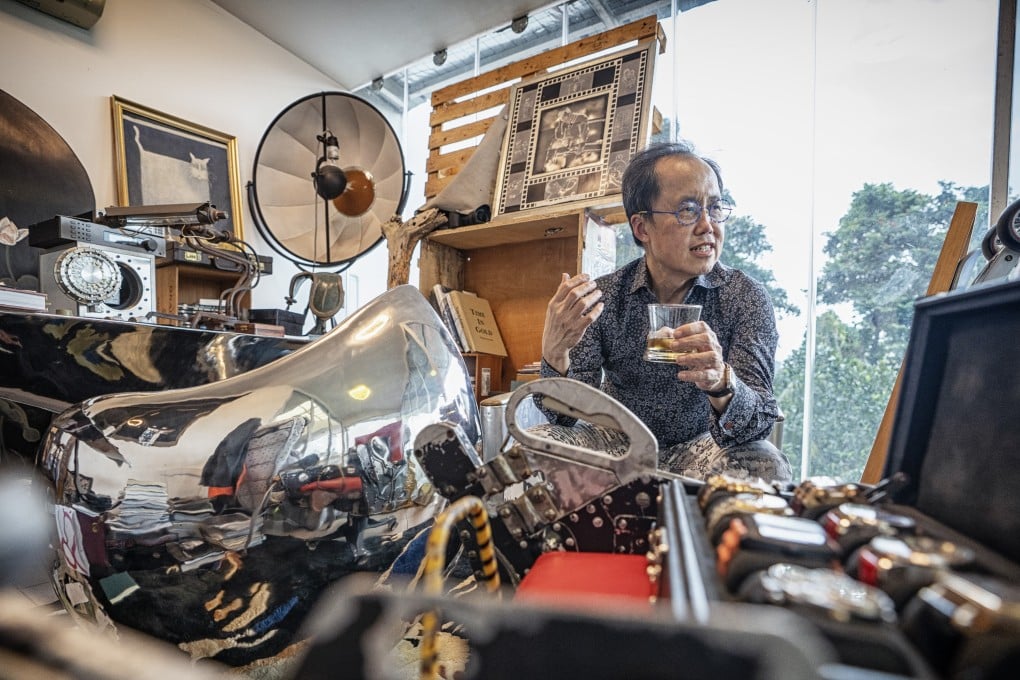

- Magpie collector Bernard Cheong sits at a Ron Arad desk with a Salvador Dali on it as he shows some of the most prized watches in his US$15 million collection

- Seeing fellow pupils at Singapore’s elite Anglo Chinese School wearing Omegas and Rolexes, he collected used Coca-Cola bottles to buy his first timepiece

Dr Bernard Cheong has what he calls a “migration box” – a travel case that holds up to eight timepieces. “I like to say that these are the watches I will take with me if I have to relocate,” says the jovial 61-year-old, one of the world’s most prolific watch collectors.

Known equally for his delightfully quirky personality that has made him a staple on Singapore’s social scene as for his watch collection, which he estimates to be worth US$15 to US$20 million, he naturally keeps some eye-popping mechanical wonders in this treasure chest.

One of his most prized pieces is a S$3.3 million (US$2.4 million) Greubel Forsey Invention Piece 1, numbered 00 in an 11-piece series. Its serial number indicates that it is the watchmaker’s personal prototype. It would not even have been sold, if not for Cheong’s clout. He believes the watch can eventually command up to S$5 million.

Dressed in a printed Tom Ford shirt and Just Cavalli jeans, he pours a liberal dram of whiskey before settling in for a long chat about timepieces in his home office. A self-taught watch expert, he has spent much of his life shaking up the rarefied and staid watch industry.

In 2011, he made history when he became the first ambassador for the Geneva-based Fondation de la Haute Horlogerie who was not from the watch industry. He helped formulate the transparent jury system, and an audited and numbered voting system, for the Grand Prix d’Horlogerie de Genève in 2002, a high-end watchmaking contest, before introducing it to Asia.