My friend Mary Quant, the London fashion designer who defined the swinging ’60s

- Quant opened a boutique on King’s Road, Chelsea, in 1955, gave the miniskirt its name and dominated young women’s fashion in the ’60s

- Because she sold factory-made clothes for the girl next door, not couture, she has been largely left out of fashion history. A new exhibition puts that right

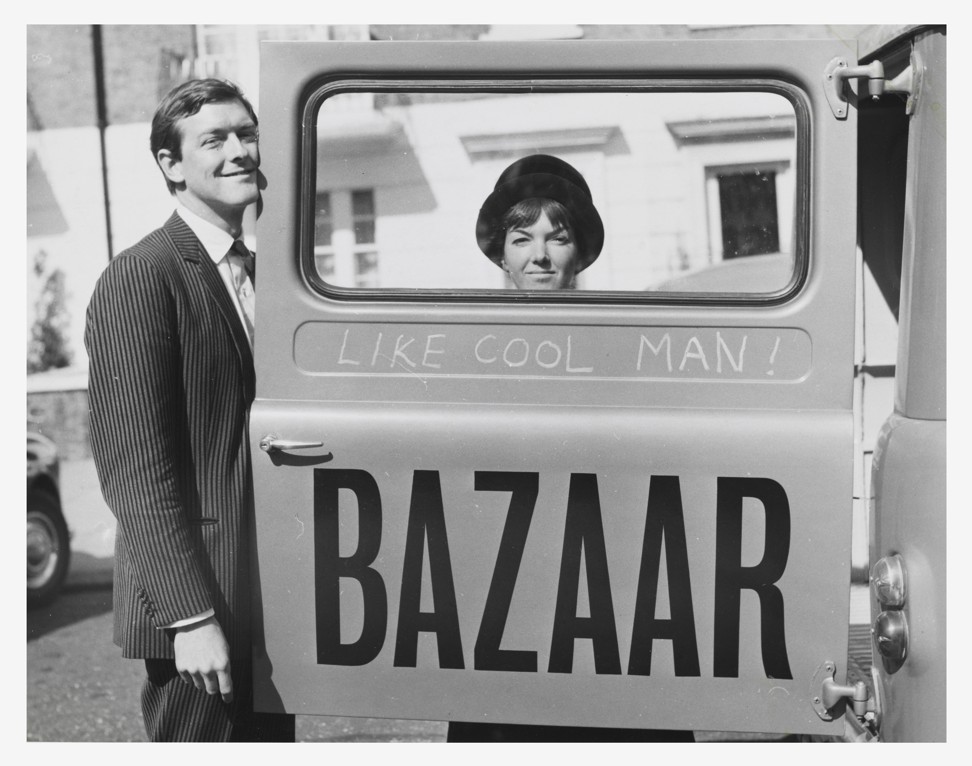

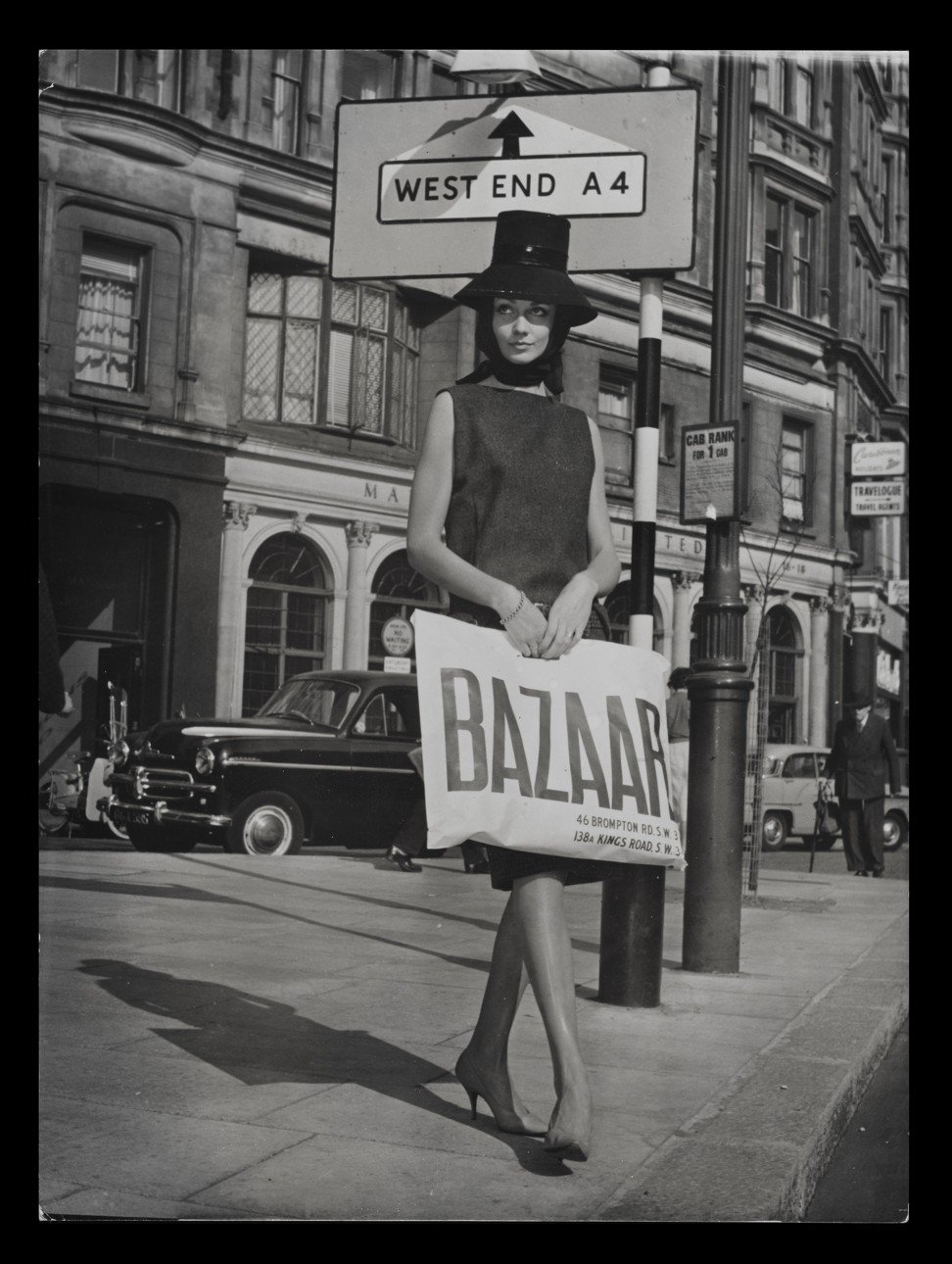

Mary Quant’s clothes – all bottom-skimming miniskirts and canary-yellow tights – embody the joyful optimism and bravery of youth. She burst onto the London fashion scene in 1955 when, aged just 25, she launched a groundbreaking fashion boutique on the King’s Road in Chelsea called Bazaar.

Over the next two decades, Mary dressed the girls of Chelsea in ice-cream-coloured pelmet dresses, thigh-baring skirts, skinny-ribbed black jumpers, and strawberry-red ankle boots. In dreary post-war London, she ensured women could finally stop dressing like their mothers.

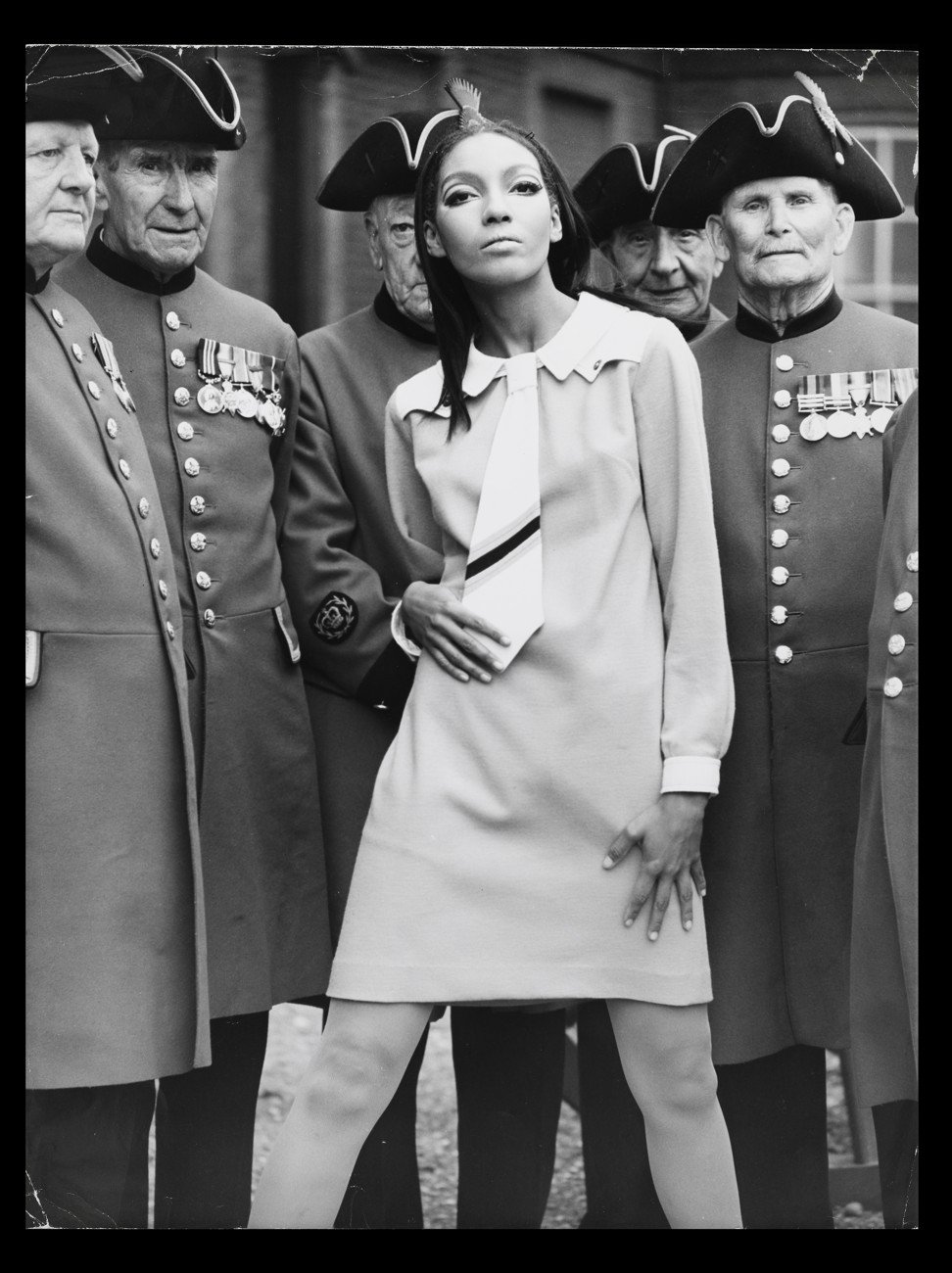

Mary was a revolutionary; she transformed the British fashion scene by turning these young women into the arbiters of style, dethroning the Parisian couturiers who had dominated the industry for the first half of the century.

I feel extremely privileged to have known her during my own teenage years, and to have dipped my first toe into the terrifyingly adult world of fashion and beauty under the guidance of one of the industry’s greatest rebels.

By then, swinging London had long given way to the “Cool Britannia” wave of the late 1990s and, in the intervening three decades, Mary’s brand had swapped miniskirts for make-up. My mother worked very closely with her and I would spend my afternoons in their South Kensington studio, ignoring my homework for walls of edible-looking face crayons, turquoise and tangerine nail varnishes and lipsticks in every colour imaginable.

It was a world away from the beauty aisles at Boots pharmacies that my friends had to make to do with, and Mary would urge me to try ever bolder colour combinations. Make-up, I learned through her, was fun and daring and about so much more than attaining an impossible ideal of female beauty.

Mary was all about being bolder, brighter and more rule-breaking. And it is this joie de vivre that London’s Victoria & Albert Museum has captured in its latest fashion retrospective, Mary Quant, which focuses on her life and designs from 1955 to 1975.

The exhibition shows Mary as someone who was as delightful as she was daring. She was famously reserved – a trait I recognised in her even when I was a painfully shy teenager. But she knew she needed to fight to break through the glass ceiling female designers faced and, as the daughter of two Welsh teachers, the rules of class-bound Britain.

As an illustration of just how well she succeeded, the exhibition opens with a blow-up photograph of Mary in a cream minidress, accepting her OBE in front of Buckingham Palace in 1966. That same dress is displayed next to the photo.

“She was part of the first generation of young women who had so many more opportunities than their mothers,” says Jenny Lister, who co-curated the exhibition. “These women have said they found themselves at university and art school, and that Mary became their figurehead for social change.

“This was a period when the world was transforming for women – not only because of the pill, but also new household machines, which meant they were no longer chained to the home. They needed a new wardrobe to represent that freedom, and – a decade before feminism – Mary provided it.”

Mary’s desire to make trendsetting fashion for the masses meant she incorporated women from around the globe into this movement. She was the first British designer to make cutting-edge clothes for the girl next door, rather than the girl with a silver spoon in her mouth, and through her ultra-cool, mass-produced designs, she paved the way for modern-day brands such as Topshop.

“I liked my skirts short because I wanted to run and catch the bus to work,” she famously said in the 1960s.

These skirts were made in factories instead of storied Parisian ateliers, and were modelled by Twiggy, Jean Shrimpton and Patty Boyd, young women who were definitely not debutantes and who represented youthful abandon rather than aristocratic hauteur. Mary had changed definition of the London it-crowd in a few short years.

This open-mindedness explains why she has never received quite as much acclaim as she deserves. “I have been wanting to do an exhibition on Mary for years,” says Lister.

The world was transforming for women – not only because of the pill, but also new household machines, which meant they were no longer chained to the home. They needed a new wardrobe to represent that freedom

“While I was at the Museum of London, I built up a collection of her clothes, and saw how Mary had this amazing influence. She was a trailblazer for so many designers, and her story influenced so many people in the 1960s and 1970s. But because she was about mass production rather than couture, she has been slightly left out of fashion history, which often focuses on grand male designers.”

Mary was neither grand nor male, but that was part of her appeal and she quickly became a figurehead for Swinging London, thanks to her Vidal Sassoon-cut bob and powder-blue Jaguar convertible. She flirted with Mick Jagger and was even rumoured to have shaved her pubic hair into a heart and dyed it green.

The exhibition is a celebration of the wildness of that era and is made up of photographs of Mary and the hundreds of unknown young women who adored her clothes. Dresses in primary colours, PVC raincoats and pattered tights make up the rest of the ground floor, while the first floor is a sea of miniskirts – alongside an explanation of how this small piece of material helped set off the entire youthquake.

By the time I knew her, Mary, who is now 89, had hung up her own short skirts and had started wearing a daily uniform of dark trouser suits with navy and white striped T-shirts. But that rebellious spirit was still with her, and she never looked back to the 1960s with nostalgia because she was always far too intoxicated by the future.

Her lifelong belief that fashion is fun, freeing and a tool for feminism had a profound impact on me – and I don’t think it’s a coincidence that in my thirties, I now have a brown bobbed haircut, an attachment to miniskirts in a year of carpet- sweeping hemlines, and a job in fashion journalism.

One wall in my London flat is even covered with black-and-white framed photographs of models in fabulous Mary Quant designs. I look at them often and know that what Mary really taught me – and a generation of women before me – was that clothes shouldn’t be a tool for fitting in or pleasing boys, but a way of telling the world exactly who you are.

Mary Quant is at the Victoria & Albert Museum from April 6 until February 2020.