Hong Kong fashion designer William Tang on rise of China, young talent and his love of knitwear as he celebrates his career

- William Tang was one of the first non-mainland designers to show in China in the 1980s and has designed uniforms for airlines including Dragonair

- As he launches two books on his successful career, he says it has become harder today for young Hong Kong fashion designers to make their mark

Hong Kong fashion designer William Tang is celebrating almost four decades in the industry with two books published this month featuring his memoirs and pictures of his collections.

Called Throwback, the Chinese-language books cover his illustrious career from 1981 – his final year studying at the London College of Fashion – all the way to last year, when he designed a special collection to celebrate jewellery brand Chow Tai Fook’s 90th anniversary.

The now 62-year-old knows he is very lucky to have had a successful fashion career.

“I came back to Hong Kong at the best time ever in the 1980s, when it was getting mature. Then the 1990s were the golden days of Hong Kong and it was the number one ‘tiger’ in Asia. I was here for those 20 years,” says Tang, who is currently battling Covid-19. “Then after 2000, China started to bloom and I was there – [actually] I was there before it was blooming. I built up all my foundations and connections there.”

His relationship with China began in 1984 when he and a group of Hong Kong designers showed their collections in Guangzhou – only the second ever fashion show in the country to feature non-mainland brands after Pierre Cardin’s 1979 show in Beijing, he says. The event received considerable media attention.

From there he was invited by Hong Kong-based retailer Chinese Arts and Crafts in 1986 to create collections working with mainland artisans in Shandong and Shanghai trained in making European-style lace. During this time he also consulted for textile and garment manufacturers and was asked to give talks to design and art students in cities including Hangzhou and Guangzhou.

The busiest 15 years of his life were in China, from 2000 to 2015. It was a time when property developers hired fashion designers like himself, as well as architects and interior designers, to give talks to clients at carnival-like events. He would present fashion shows, even giving hair and make-up makeovers to members of the audience.

“I was invited all over China. For holidays like May 1, October 1 and before Chinese New Year our team would be the busiest, like mad bees flying everywhere,” he says. “For example, in Guangzhou I would do one show in the morning, one show in the afternoon, at two different venues. [If a client] in another city wanted to do a show, they would rather change the date [if I was not available], or else I would send a couple of good models to show my clothes without me with a discount.”

Tang became known for knitwear early in his fashion career as Hong Kong transitioned to manufacturing the material.

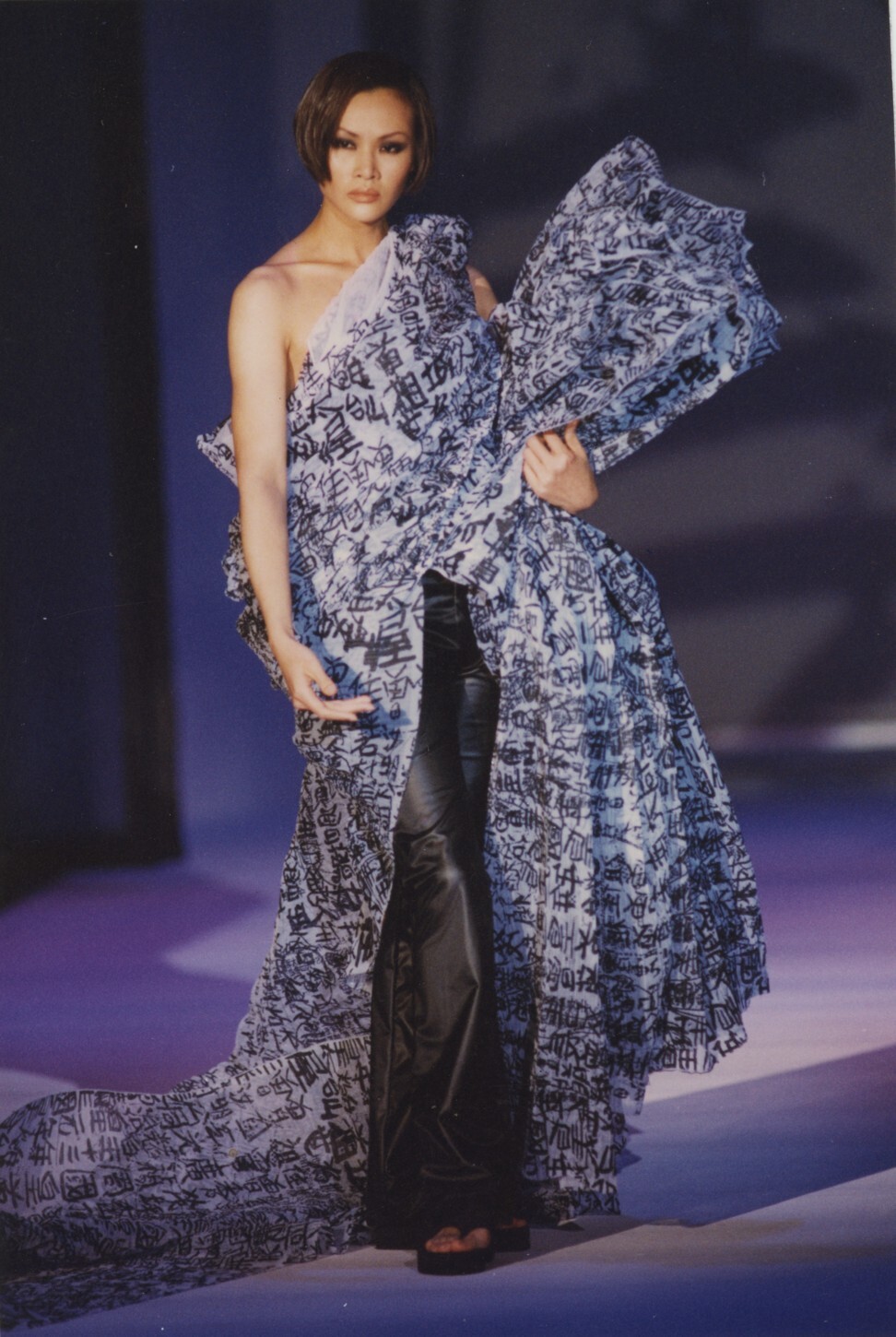

For the final outfit of the show, Tang created a dress with a long fishtail train covered in Tsang’s distinctive graffiti.

“We have a Chinese saying: ‘An issue can be as long as a roll of fabric – so long that there’s no point in talking about it because it’s too complicated,’” Tang says. “When I finished shaping the dress on the mannequin, I was supposed to cut the fabric, but it was so beautiful I didn’t want to cut it. All of a sudden that idiom came to mind – the roll of fabric with the words written by the King of Kowloon, claiming his family owned that land but it was taken over by a British queen. That, to the King of Kowloon, was the history of Hong Kong – it’s complicated.”

Tang says Hong Kong’s diminishing importance in the region’s fashion industry was a perfect storm of increasing labour costs, local artists seeking exposure in Chinese music and films, the media not covering home-grown talent, and the culture of online shopping. As a result, it has become harder for the upcoming generation of local fashion designers to make their mark.

“They have huge competition from young talent in China. I am quite sad actually,” he says. “I’m not saying they are not doing a good job; the [Hong Kong] market is so small, there’s not much room to branch out. Even young Chinese designers are not having a good time [here], too, for the last few years.

“The industry is getting more and more competitive. People think it’s much easier to have an online shop, but it attracts more competition. But fashion around the world is the same – you don’t hear new names any more in the past five to 10 years. The last biggest influential name was Alexander McQueen. Whoever the successors are, there is no comparison any more. That’s what’s happening in fashion.”

In the meantime, Tang has been happily married to surgeon Clement Chen Tzu Hsin for almost three years and is keeping busy writing articles for Apple Daily, hosting a talk show on RTHK, and plans to write a book about his parents, in particular his mother, whose family settled in Ecuador.