Trendy Asian beauty routines’ cultural history gets erased in America, and some are fighting back

- Gua sha has gone viral on TikTok but how many know of its roots in Chinese traditional medicine, or pimple patches’ and cushion compacts’ Korean origins?

- Asian-Americans working in beauty feel hurt and offended by brands’ whitewashing, and say people may misuse products if they don’t know their origin stories

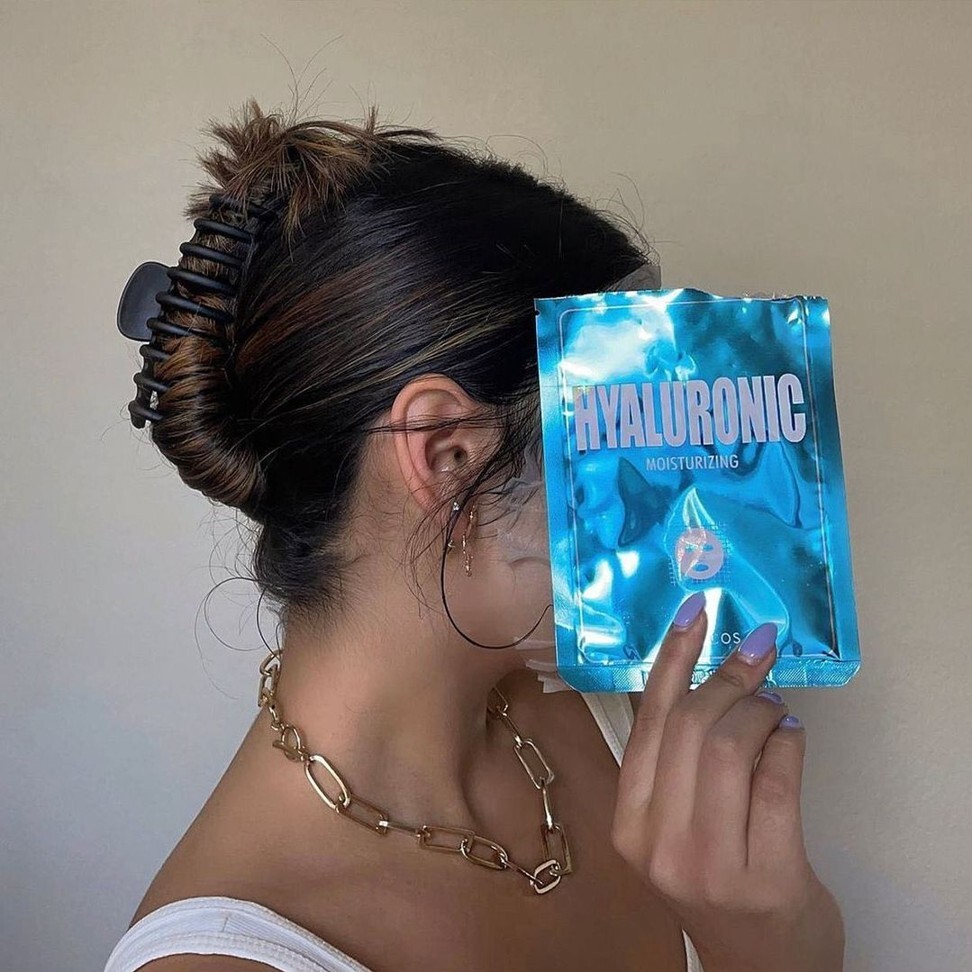

YouTube is full of videos promoting 10-step skincare routines, and supermarkets are stocked with serum-soaked sheet masks – all while gua sha results go viral on TikTok. But do you know the origins of these products and practices? Maybe not. And that’s a problem.

Charlotte Cho, co-founder of Soko Glam, a company that specialises in Korean beauty products from sheet masks to cleansing balms, has been helping to introduce Korean beauty to the US for almost nine years.

“As time goes on, I think people are forgetting that these innovations are coming from Korea,” she says. “A lot of the Western and American brands are adopting these ingredients and products into their own product line, but oftentimes the way in which they introduce a product doesn’t shed light on the origin story of the innovation that they adopted from.”

“These products and practices are actually manifestations of diverse Asian cultures,” she adds. “Our voices have long been marginalised in the mainstream beauty industry, and it is essential that our ... growing contributions be recognised for both their historical and contemporary significance.”

Gua sha entails scraping the skin to stimulate circulation and improve its appearance. Traditionally practised on the body, it is now also used on the face.

Sandra Chiu Lanshin, a licensed acupuncturist who founded the healing studio Lanshin, says not giving proper credit is also offensive.

“It offends me when brands profit from ingredients or traditions like gua sha without deep reverence for the culture and respect for Asian people, who have been carrying the traditions for generations and centuries,” Chiu says. “It would mean a lot to the community to see our culture properly represented and our traditions communicated as intended.”

Angela Chau Gray, co-founder of skincare line Yina, says not sharing the origin stories of Asian products “marginalises a huge population”.

Chiu says people are “erasing Asian culture” by whitewashing some of these practices.

There’s nothing wrong with using ingredients that are traditionally from different cultures … the intent is show respect for all of these traditions. Don’t pass them off as your own.

“It’s easy to call something a ‘trend’ and offer it in a watered down way that’s disconnected from the more complex – and rewarding – aspects of the tradition,” she says, explaining that misinformation risks degrading a practice’s efficacy. “When brands and influencers make claims and provide uninformed support, it inevitably leads to disappointed consumers who question the credibility of TCM.”

That’s why learning from people who understand the background and best techniques for a product is important. Jennifer Lee, vice-president and co-founder of K-beauty brand Lapcos, said she saw this happen when educating people about sheet masks.

“People would use it and then wipe everything off, and I was like, ‘No, no, don’t do that,’ you want to let it soak in,” she explained.

Acne? Eczema? Doctor prescribes Chinese herbal medicine creams

While Cho is “really excited” to see Korean beauty part of the mainstream and is “very hopeful for the future”, she says brands can be more mindful.

“It’s not about shaming companies or brands, I think it’s just about sharing this information,” she says. “There’s nothing wrong with using ingredients that are traditionally from different cultures … the intent is show respect for all of these traditions. Don’t pass them off as your own.”

Chiu says “it’s critical” for brands and individuals profiting from Asian heritage practices or products to actively share and educate consumers about their origins. “Otherwise, it simply erases the culture.”

Cho also thinks it’s a “win-win” for brands and consumers to be more transparent because “customers actually love hearing the origin stories”.

“This innovation is trending outside Korea now, because it is such an easy, seamless way to apply foundation,” Cho explained.

The popular pimple patches seen on the market today, which use hydrocolloid (dressings with a gel-like surface) to help clean out impurities and heal acne, also have roots in Korea.

“It’s not like Koreans invented hydrocolloid, [but] they were smart enough to tackle acne as a wound,” Cho says.

Lee thinks bringing “any type of accessibility of skincare to the world is beneficial for everyone”. Consumers can also do their part, Lee says, by purchasing from Asian-owned brands. “Seoul is one of the capitals of the beauty world and Koreans know what they’re doing,” she laughed.

Chiu says consumers looking to learn about a TCM practice like gua sha should also “turn to the people who grew up with it and understand it on a deeper level”.