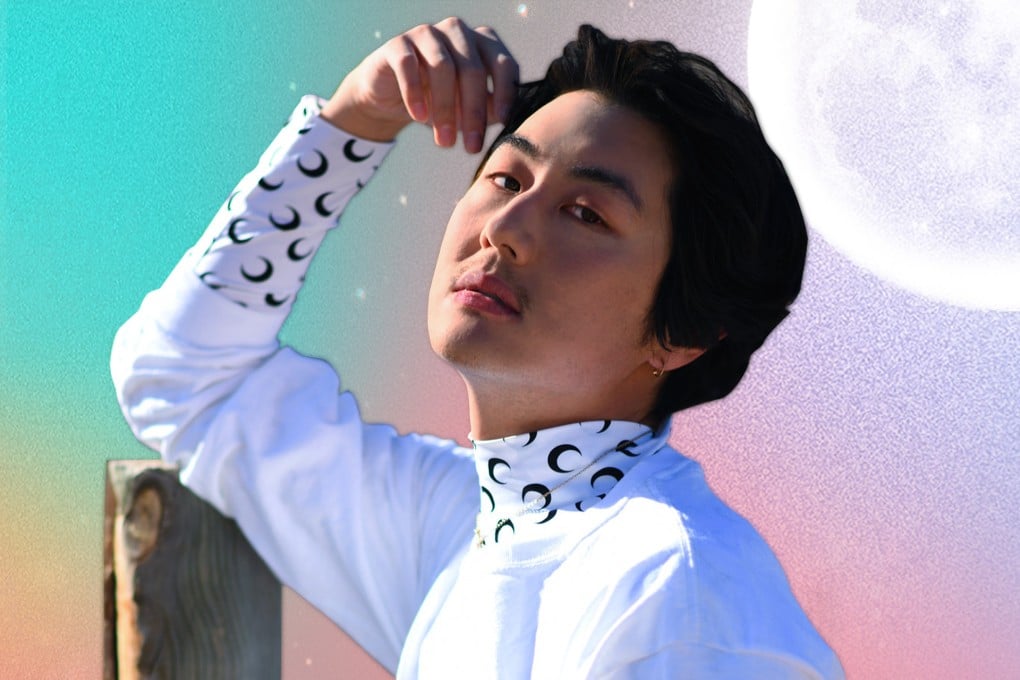

Asian-American diversity champion on his new skincare line, China plans and why his 15-year-old self would be proud of him today

- Unhappy with the lack of gender-inclusive representation in beauty products, David Yi went on a mission to create his own

- Good Light, a skincare line with the tagline ‘Beauty Beyond the Binary’, launched in the US in March, and Yi recently announced plans to expand to China

David Yi was a vocal proponent for diversity long before it became the politically correct thing to be. As one of the few Asian-Americans growing up in the US city of Colorado Springs, he started a club in high school called the International Diversity Council and worked on the school paper, where he wrote about Asian-American issues.

“I didn’t have many friends but it didn’t matter to me because I spoke truth to power,” he said on a recent Zoom call. “I was 15 years old and standing on stage in front of white folks talking to them about why they should care about diversity and why inclusion matters.”

Those early experiences must have formed a template of sorts for Yi, who in 2016 put his forthrightness to good use by founding verygoodlight.com, a digital magazine that features colourful, relevant and incisive stories about things like why unibrows should be embraced, the realities of polyamory and protecting your mental health while on social media.

The site, Yi says, was a natural progression for him given his teenage years as a self-professed “storyteller” and his background as a journalist (he worked at Women’s Wear Daily and the New York Daily News, and launched beauty and fashion coverage at Mashable.)

The website was also ahead of its time in many ways. Yi recalls the first story on the site about the experience of being an Arab-American in a “Trumpian” era.