How to fight climate change: re-wear your clothes – if we all used them for twice as long as now, emissions from clothing would fall 44 per cent

- It’s no secret that the fashion industry has a climate problem – buying less, wearing things for longer and renting or reselling clothes reduces that problem

- Wearing the stuff you own for longer means that you will buy less, thus avoiding the greenhouse gas emissions that would be generated producing new items

A small, simple and cheap way to help limit climate change is to wear the clothes already in your wardrobe roughly twice as many times as you might have otherwise before tossing them.

If everyone doubled on average the number of times that they wore a garment, this could reduce greenhouse gas emissions from clothing by 44 per cent, according to a 2017 report from the charity Ellen MacArthur Foundation, later echoed by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).

Here’s why: wearing the stuff you already own likely means that you will buy less in the future, thus preventing emissions generated during the production of new items.

“The way that the sales were growing, people were starting to own more and more clothes,” said Laura Balmond, Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s fashion initiative lead.

The numbers are undeniable. “It wouldn’t be physically possible to get as much wear out of your items as it previously had because people have got a lot sitting in their wardrobes,” she says.

On its current path, the Ellen MacArthur Foundation estimated, the industry could use up more than 26 per cent of the carbon budget remaining if we are to limit global warming to 2 degrees Celsius by 2050.

Less than 1 per cent of clothing collected for recycling worldwide is turned into new items.

Fuelled by the fast-fashion craze and social media, “there’s sort of this desire for newness”, said Balmond.

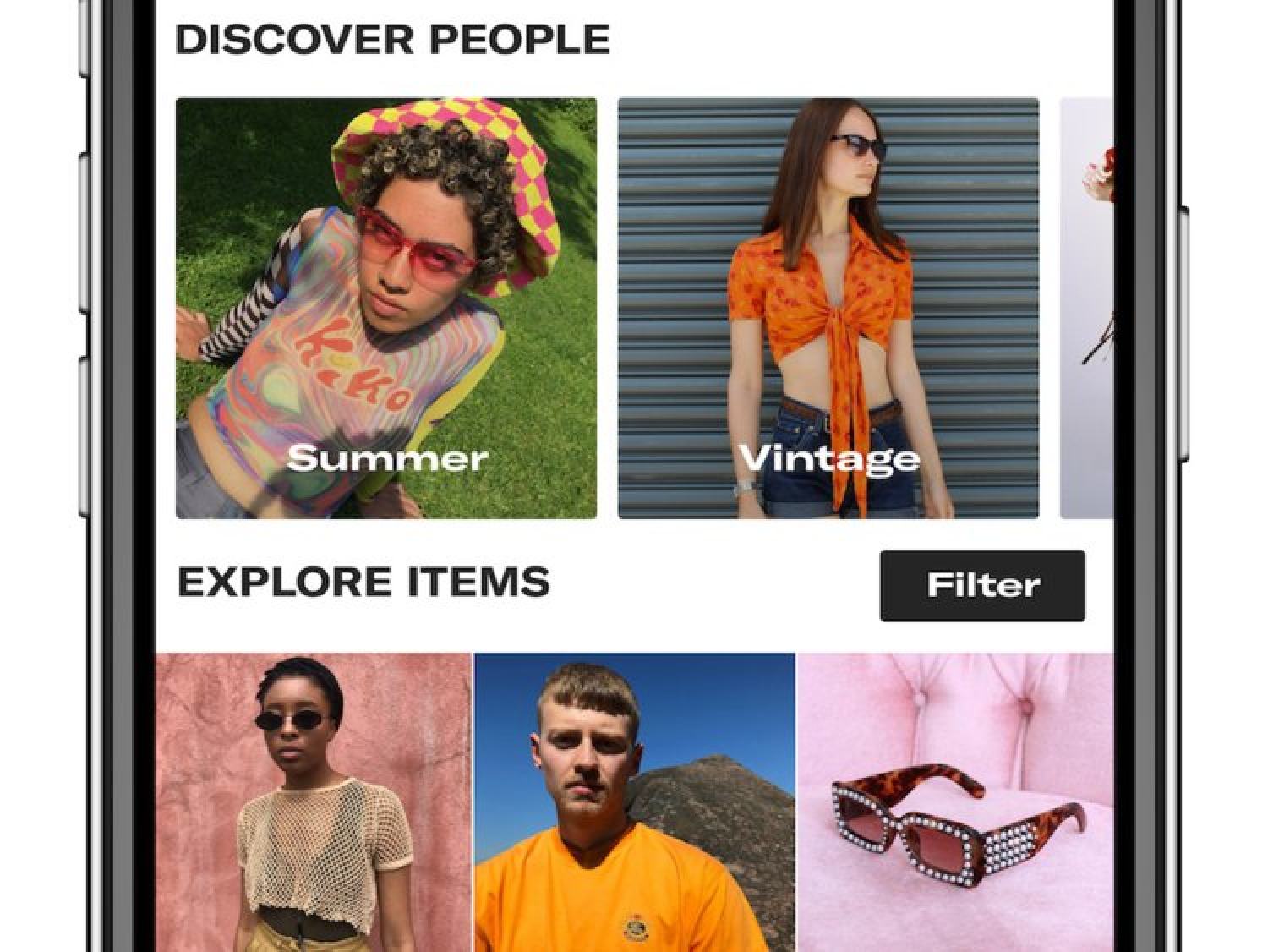

With companies increasingly announcing strategic goals and programmes in the name of circularity, it can be hard for customers to distinguish what has real impact and what is just greenwashing. But shifting customer perspectives could open the door to businesses more in line with clear circularity targets.

The challenge is, Balmond said, “if we can shift the mindset from it being a brand new product to being new to you”.

The shift is already under way. After hosting “Worn Wear” events for customers to bring their old jackets, leggings and other items for repair or exchange, US outdoor clothing retailer Patagonia launched an online marketplace with the same name in 2017 to expand the programme.

The second-hand market grew from about US$11 billion in 2012 to $35 billion in 2021, according to ThredUp’s 2022 resale report, and it’s projected to dramatically jump to US$82 billion by 2026.

The business has expanded again and again in the years since, adding accessories and plus-size items to the rentals, followed by bricks-and-mortar stores and monthly subscriptions. In October 2021, the company went public.

While sales climbed this year, Rent the Runway reported a net loss of US$42.5 million in the first quarter of 2022.

Circularity will only get us so far in reining in greenhouse-gas emissions. “We have endless talk about circularity,” said Veronica Bates Kassatly, an independent fashion analyst.

The focus instead should be on the sheer volume of items being produced. “We have far too much and we wear it far too few times,” she said.

Some research has indicated people toss items of clothing after wearing them only seven to 10 times. But what would be a reasonable number of times to wear a garment: 60, 100, 200? Should there even be a target?

“It’s hard to give a number,” said Jin Su, an associate professor in the department of consumer, apparel and retail studies at the University of North Carolina Greensboro in the US. Su added that such a goal would have to vary by clothing type and fabric.

Perhaps the closest thing to this number is a new durability metric for jeans. Led by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, a coalition of academic experts, brands, retailers, manufacturers and others developed jeans guidelines, deciding that jeans should be able to withstand a minimum of 30 washes at home while still retaining their high quality.

That means someone would have to wear them more than 30 times to get the most out of them.

The way you wash your clothes also matters from a climate perspective. While the biggest share of the emissions tied to apparel comes from textile production – 41 per cent – the second largest source is from consumption, which largely comes down to the energy associated with washing and drying.

To minimise this footprint, wash using cooler water and line-dry your items, experts recommend.

Not needing to wash your clothes as much helps, too. Wool is generally more expensive than plastic-based clothing, but it’s good at wicking away moisture and is highly durable, according to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation.

To showcase the powers of wool, Wool&Prince founder Mac Bishop wore a wool shirt for 100 days without washing it. That challenge went viral and helped launch Bishop’s clothing line; he later started a parallel company for women’s clothing called Wool&.

Now the twin companies reward customers who wear an item of their clothing for 100 days straight (washing is highly encouraged) with a discount off their next purchase. More than 4,000 people have completed the challenge, according to Rebecca Eby, Wool&’s manager of customer experience and communities.

“I started as a customer who did this challenge and it changed my life,” Eby said. She said she almost exclusively wears natural fibres now, mostly Wool& clothes, and does a lot less laundry.

She’s heard from many customers who perhaps started the challenge to get the discount to buy more and ended up changing their habits in the process.

In promoting a lifestyle of wearing and needing less, Wool& is inevitably limiting its reach as a company. It’s something the entire fashion industry may eventually wrestle with, and Eby acknowledged the awkwardness.

“It’s definitely something that we struggle with a bit,” she said.