Your fast-fashion hauls will pollute Africa’s beaches for years – second-hand shops cannot keep up

- Shoppers are buying far more clothes and discarding far more – and the charity sector is forced to dispose of textile waste it cannot reuse in a variety of ways

- Much of it ends up in African countries like Ghana, polluting its seas, rivers and forests ‘for decades or even centuries to come’, activist says

When putting yet another item in an already overstuffed wardrobe feels all but impossible, you know it is time to Marie Kondo your clothes.

Some of our cast-offs we sell online; the rest we take to charity shops – and after we have dropped them off, we walk away with the satisfaction of knowing we have done something good.

Except that it is a lot more complicated than that.

The result is that the charity sector is now in charge of disposing of vast amounts of textile waste, which it is forced to do in a variety of ways – few of which are good for the planet.

The price of fast fashion – and what is being done about it

In Britain, for example, only about 20 per cent of donations can be resold in second-hand stores – mostly because the items in question are too soiled, too damaged to be used or too cheap to be of value.

A further 10 per cent are either sent to recycling hubs, where they are turned into reusable fabrics that smaller brands and major players like Marks & Spencer can buy, or they are sent into the building industry and used as insulation or to stuff furniture.

In places like Hong Kong, a small population means the proportion suitable for resale is even lower – and any clothing that is not sold domestically, whether as clothes or in other forms, is sent to Africa.

According to global development charity Oxfam, an estimated 70 per cent of clothes donated in first-world countries ended up in Africa in 2015.

The most obvious example of the hugely destructive impact fast fashion brands have on the ecosystem can be seen on Ghana’s once pristine white-sand beaches.

The Atlantic-facing West African country is a place of incredible natural beauty, but its seas, rivers and forests are now clogged with clothing made thousands of kilometres to the east, and worn by people from all over the world.

“We’ve been conditioned by fast fashion brands, via marketing, to over-consume – to think it’s normal to buy a new outfit for a hot date, to walk out of a store with a sack full of clothes, that US$10 is the correct price for a shirt. It’s not. You are contributing to global poverty by buying that cheap shirt.”

“Think of your fast fashion purchases that way, and you’ll stop. Basically: if the price is too cheap to believe, it’s too cheap – because after you have worn it once or twice, it will be out there, polluting parts of Africa for decades or even centuries to come.”

Countries like Ghana cannot cope with the sheer quantity of clothing being sent to them. Each week, the nation receives 15 million items of used clothing. Once these bundles of clothing have entered the African ecosystem, the better-quality pieces are sent to heaving markets that have been set up in Kenya, Nigeria, Ghana and Zambia.

The problem comes from the 40 per cent of the products sent to Africa that have to be discarded once there because of their poor quality.

Customers and even charities often see the cycle of sending clothes to Africa as a relatively environmentally friendly one, but the truth is that much of the industry is dedicated to moving clothes that would end up in dumpsites in the West to dumpsites in Africa.

It would be better to keep them where they were: Ghana does not have landfills or incinerators, so many of these clothes end up on the ocean floor, polluting entire ecosystems and killing sea life.

There is also a human cost: Africa’s textiles industries cannot compete with clothes that are essentially free – one local news report suggested that, a few decades ago, 500,000 people were employed in Kenya’s textile industry; today that figure is around 38,000.

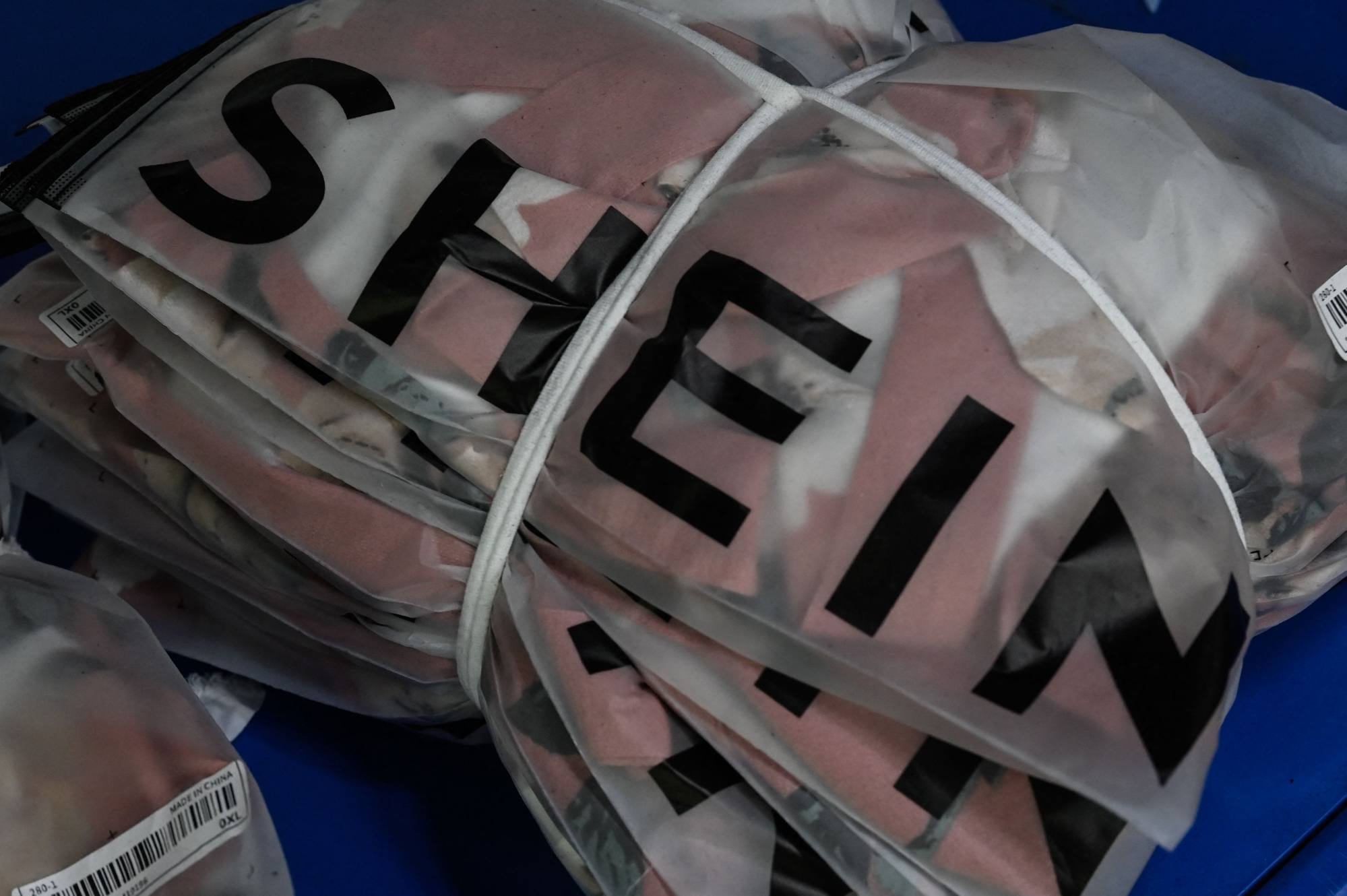

Shein’s name is often mentioned in this debacle because of the sheer quantity of clothes it produces; and the sheer quantity of Shein produce that is thrown away. Earlier this year, the ultra-fast fashion brand was praised for making a donation of US$15 million to a charity working at Kantamanto in Accra, the world’s largest second-hand clothing market.

However, at the same forum at which this was announced, Liz Ricketts, director of the Or Foundation, which works with Accra’s textile-waste workers, spoke up.

“They are economic migrants from north Ghana, and are often women and children, some as young as six,” she said. “They’re carrying clothing bales on their heads which weigh 55kg [120 pounds], being paid a dollar a trip, and coming home to sleep on concrete floors.

“Some carry their babies on their back. Sometimes they fall backwards because of the weight of the bales, and their children are killed.”

A sobering image we should all keep in mind the next time we are tempted to succumb to the saccharine hit of a fast-fashion purchase.