Hong Kong-based director’s road movie premieres at Rotterdam festival

Yang Zhengfan’s Where Are You Going? is too melodramatic and contrived for Hong Kong audiences but may resonate overseas; another local director shows film with ‘umbrella movement’ theme

As a film festival director’s speech goes, Bero Beyer’s was one incredibly socially engaged affair. Speaking at the opening ceremony of the International Film Festival Rotterdam on January 27, Beyer paid tribute to filmmakers who have defied powers who “feel threatened or offended by the outspokenness of their art”, and said the festival is committed to provide “an open environment” for such suppressed voices to thrive.

“We have always presented filmmakers who swim against the stream, whether artistically or politically, and we should continue to do so and we should be aware that it’s quite a feat for filmmakers to be doing that,” Beyer told SCMP.com later. “We’re not a political institution – but we are an institution here to celebrate the freedom of cultural expression through cinema.”

We’re not a political institution – but we are an institution here to celebrate the freedom of cultural expression through cinema

Beyond its centrepiece – that is, the Tiger Awards competition – the festival hosted sections dedicated to identities and community cameras, a compilation of shorts shot by Syrian filmmakers, and new, politically charged work by Catalan auteur Pere Portabella (General Report II: The New Abduction of Europe) and Japanese legend Masao Adachi (The Artist of Fasting). There were Hong Kong entries nodding to the city’s pro-democracy protests last year, too.

As Ten Years continued to whip up a political storm in Hong Kong, two other films were playing torch-bearer for the “umbrella movement” in Europe. As part of the short-film omnibus “This Is Where Reconstruction Starts”, commissioned by the festival, Ying Liang’s A Sunny Day – which has since made its domestic bow at the Hong Kong Independent Film Festival – revolves around an activist’s exchanges with her retirement-home-bound father just as the police fired tear gas at demonstrators in the city’s Admiralty and Central districts.

READ MORE: Ten Years, the Hong Kong film that beat Star Wars at the box office, and the directors behind it

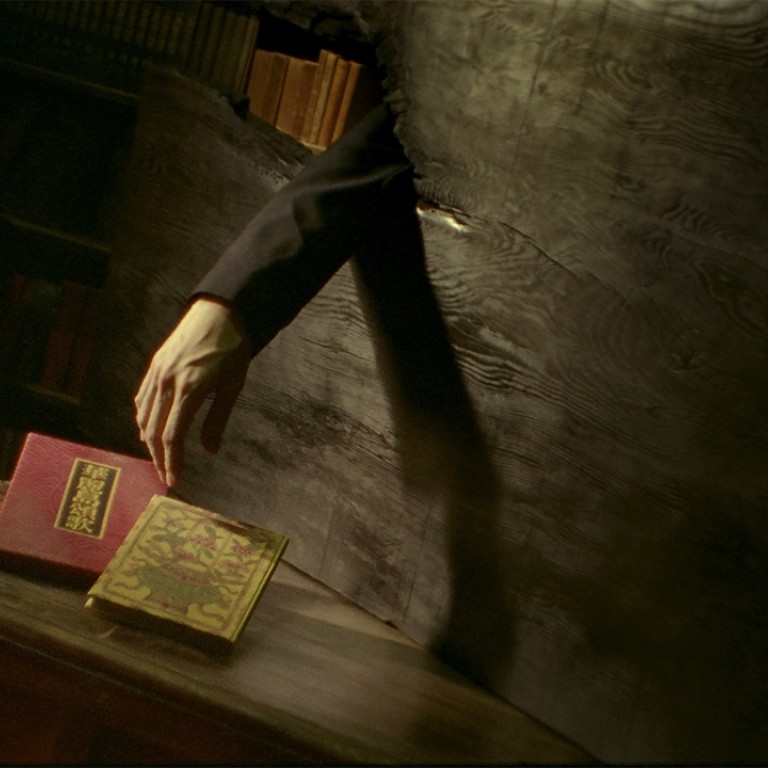

Less explicit and more formalist is Where Are You Going? Hong Kong-based Chinese director Yang Zhengfan’s two-hour-plus “road movie” consists of a near-endless stream of city streetscapes seen through a windscreen. Meanwhile, conversations – purportedly conducted by unseen fictional characters inside taxis – lay out the struggle for those in Hong Kong in accommodating themselves to the unfolding social narrative.

Among the voices are those of aggressive Chinese tourists, petty-minded middle-class Hongkongers, a British man lamenting his departure for his next neo-colonial adventure in Shanghai, and a student who disputes his soon-to-emigrate father’s dismissive remarks about 2014’s Occupy protests and insists people – or the young generation, at least – should fight to become masters of their city and their own fate.

In his director’s notes, Yang says he still feels like an outsider despite having lived in Hong Kong for five years. Unfortunately, that separation from reality is very much evident: while ticking off nearly each and every major social concern he could find in the media, his screenplay offers awkward, exposition-heavy conversations conducted by caricatures. While this bullet-point approach might wash well with international audiences, Hong Kong viewers will probably be put off by the melodramatic delivery of the contrived dialogue.

Somehow hidden amid the shorts programme, Simon Liu’s Harbour City is the most intriguing Hong Kong film at Rotterdam this year. Placing on screen two streams of manipulated images from material shot on 16mm stock, Liu’s 14-minute piece – which counts obvious influences from British artists such as Tacita Dean and Ben Rivers – is akin to a manic reverie of Hong Kong’s past and present.

Footage from local markets sits next to footage of street signs in Britain, while shots of a dim sum lunch on the left do battle with film of cakes and tea at the Mandarin Oriental. Devoid of sound, the film demands interpretation on the viewer’s part – is it a lesson on history, or merely history reduced to visual totems, just like the prevalent yearning in Hong Kong for a cleansed and processed version of its colonial past.

Of course, the Rotterdam festival – with its hundreds of titles and a string of related exhibitions – offers a lot more than this. A strong supporter of independent Asian cinema since its inception 44 years ago, the festival has long had strong links with filmmakers from afar: one of the most significant sections this year is Burma Rebound, an installation of video work from the Southeast Asian country.

Closer to home, the festival featured the debuts of two directors, one Taiwanese, the other Chinese. Huang Ya-li’s Le Moulin (a highly artistic documentary about a group of Japanese-speaking Taiwanese surrealist poets in the 1930s) and Cui Yi’s Of Shadows (which documents the struggles of shadow puppet performers in the far-flung hinterlands of northwestern China). By bringing historically and socially marginalised voices to the fore, Huang and Cui have embodied the spirit of discovery inherent in the Rotterdam film festival.