Ageing gracefully: How to get the best out of life's luxuries

Cheese, ham, balsamic vinegar and port are best appreciated when they've been afforded sufficient time in which to mature, writes Annabel Jackson

Delicacies such as lobster straight from the ocean, freshly shucked oysters or the first spears of white asparagus are at their best when fresh. Other gourmet items take time to reveal their personalities.

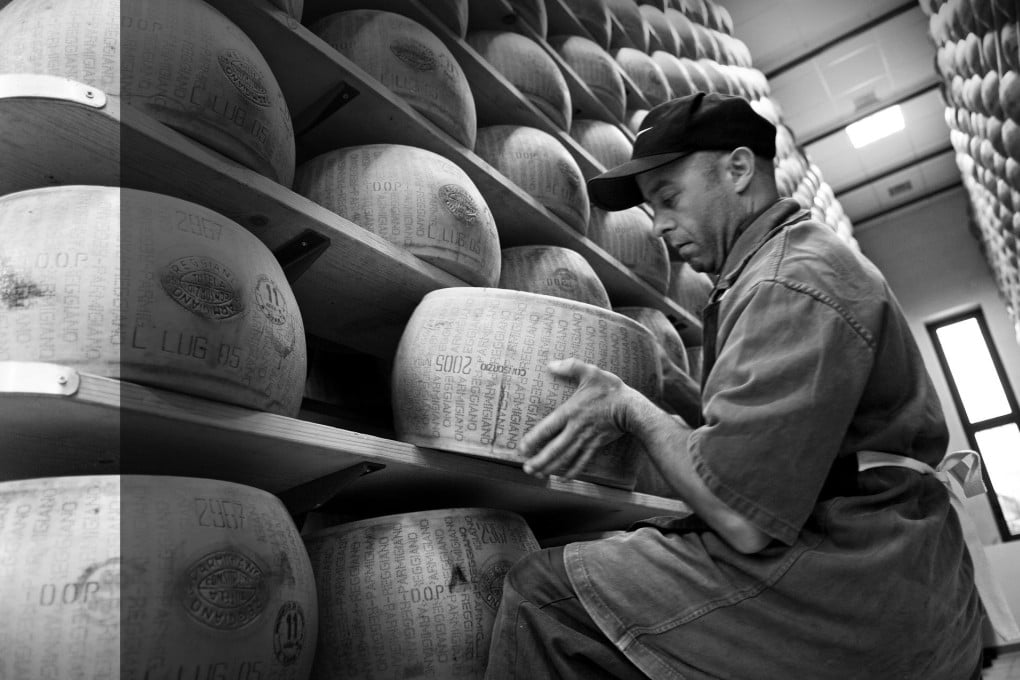

"Parmigiano should be eaten like chocolate," says Giorgio Cravero of G. Cravero, a family company that has been selecting and maturing Parmigiano-Reggiano since 1855. The cheese is made in Italy's Emilia-Romagna, where it is aged for 12 months.

Of the region's 390 producers, Cravero selects from just four, three of which are in the village of Benedello. "Terroir," Cravero says. "The local grass is very special. We look for 'soft and sweet' rather than the commercial 'hard, dry, sandy, spicy, piquant'."

His job is to bring the cheese to the next stage. At the family facility in Bra, birthplace of the "Slow Food" movement, the wheels are aged at 17 to 18 degrees Celsius and 70 per cent humidity for up to 24 months.

Robots flip the wheels every two weeks. During the summer they are also wiped, by hand. "During maturation, taste and texture change a lot," he says, "and wheels are at their peak at 24 to 30 months."