Taste test of 1966 Bordeaux shows the risks and rewards of letting good wine age

Drinking old wine can be a gamble, but an evening spent sampling 10 contrasting 50-year-old Bordeaux brings home the idea that a bottle of wine is a slice of time and place

Just the decanting was an art in itself. Olivier Bernard, owner of Domaine de Chevalier and our host for the evening, carefully prised the 50-year-old corks loose from the bottle. Slowly, he turned them over in his hand, then sniffed at them with something approaching first suspicion then approval. Well, in all but one case; a 1966 Pape Clement was discarded.The level of the wine barely reached the shoulders of the bottle, which meant that the oxidised smell came as no surprise. The rest of the wines – 10 in total, all Bordeaux in both red and white – were set carefully to one side, ready to be drunk over supper.

This was an unusual evening, to say the least. Tasting so many 50-year-old wines in one sitting is an incredible way to bring home the idea that wine is a slice of time and place. And that there is something magic about the soils, grape variety and climate in Bordeaux that means even white wines can go the distance when the conditions are right.

The 1966 vintage in Bordeaux wasn’t the best of the decade (that accolade would go to 1961) but it was good, and although the tannins when young were a little tough and tight, you will be happy to hear that 50 years has been more than enough to soften them up.

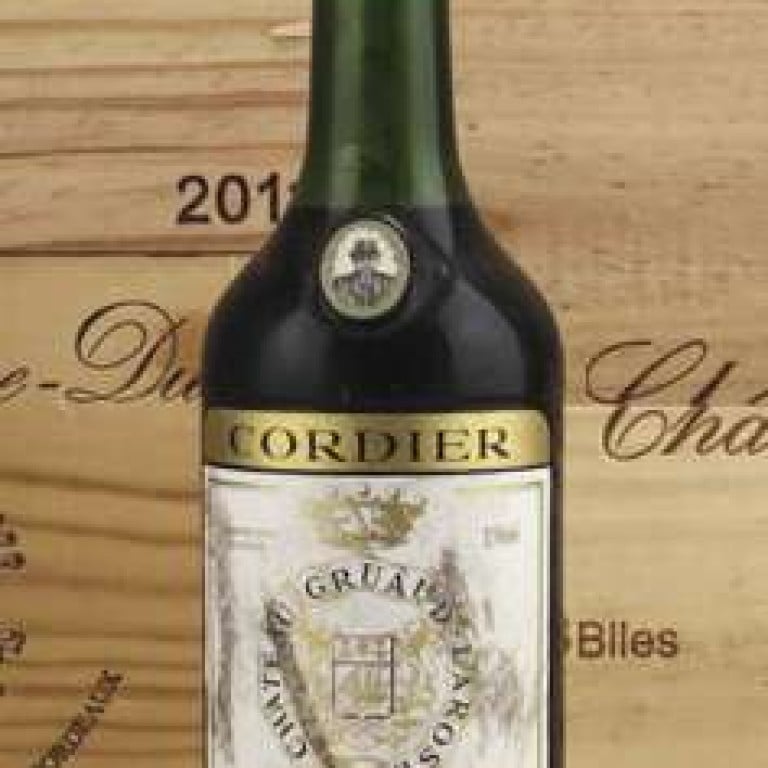

They were not all in perfect condition, of course. Chateau Gruaud Larose 1966 was still just about holding on, but on its last gasps, as was Pomerol’s Chateau Bonalgue. The same could be said for the Chateau Malartic-Lagravière, although it was in a half bottle and a white wine, so should perhaps be given a round of applause for showing any life at all. But Domaine de Chevalier (in both colours), the white Chateau de Fieuzal, Chateau Pichon Comtesse, La Mission Haut-Brion, Chateau Latour à Pomerol and – oh, especially – Chateau Cheval Blanc and Chateau Palmer were all just astonishingly vibrant, beautiful wines, even at 50 years old.

They were in varying stages of evolution, but each one displayed the subtle array of autumnal, smoky, spicy flavours that make well-aged wines such a thrill to try.

Tasting older wines requires patience, empathy and a sense of adventure. For the first decade or so, good quality Bordeaux reds are bristling with fruit and tannins from the cabernet sauvignon and merlot grapes, while the young whites major on star-bright floral and fruit aromatics of sauvignon blanc and semillon. The moment of crossover from these primary aromas to the more subtle tertiary aromatics of an older wine differs widely, depending on vintage and – even more important – the individual producer and their location.

So how do you know which wines might just reward being put out to pasture for this long? It can be a lottery in many ways, because any problems with storage will be magnified after a couple of decades – and even perfectly stored wines can show huge bottle variation, most typically because bottling until the 1990s was a far less exact science than it is today. But there are some rules.

The most important is to try to assess the structure of a wine when it’s bottled. Whatever the colour or style, if you find concentrated fruit, restrained power and a fresh backbone of acidity in a young wine, you are likely in the presence of a bottle that will be able to age. It’s why there are plenty of white wines that taste better with a bit of ageing. You can confidently expect pretty much any sweet wine, such as Sauternes, Tokay, and most ports, to age well. Some dry whites also, like a good quality chardonnay, riesling, Loire chenin or certain Pessac Léognans from Bordeaux can all age brilliantly. And for both white and reds, experience matters.

The great names might not get it right every year, but you can at least be sure that the idea of someone opening a bottle in 50 years time is part of their mindset during bottling.

Even if their condition is a gamble, many older wines are today available for less money than the more recent vintages of the same wines. Which makes taking a risk seem like the sensible option.

Jane Anson is the Louis Roederer Wine Feature Writer of the Year 2016