How China’s iconic White Rabbit sweets went from a Shanghai favourite to being known the world over

After first appearing in the 1940s, the candy’s iconic branding and edible rice paper wrapping gave it a special place in China’s collective memory and history. They are now exported to more than 40 countries worldwide

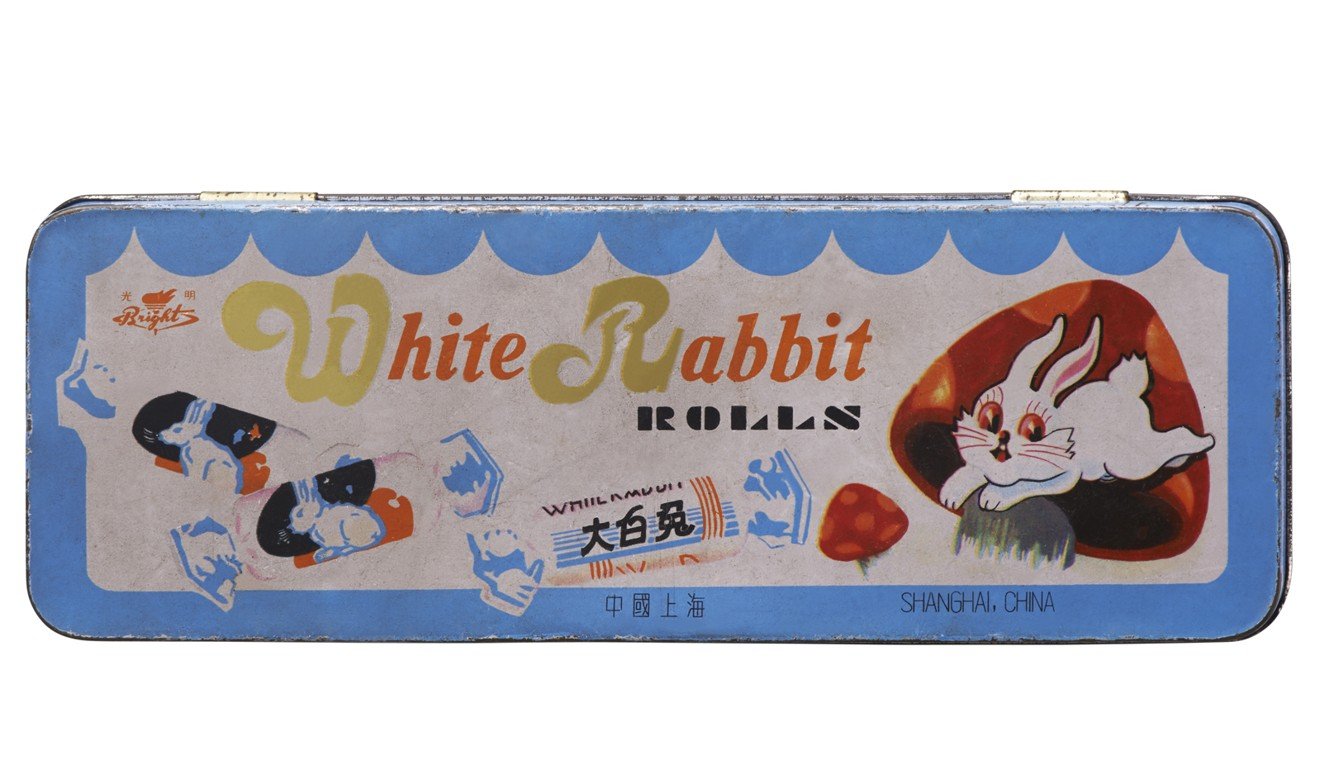

Ask anyone in Shanghai to name their favourite candy and there will only be one answer. The familiar white, red and blue wrappers of White Rabbit Creamy Candy have been a staple among sweet tooths in China and overseas for nearly eight decades.

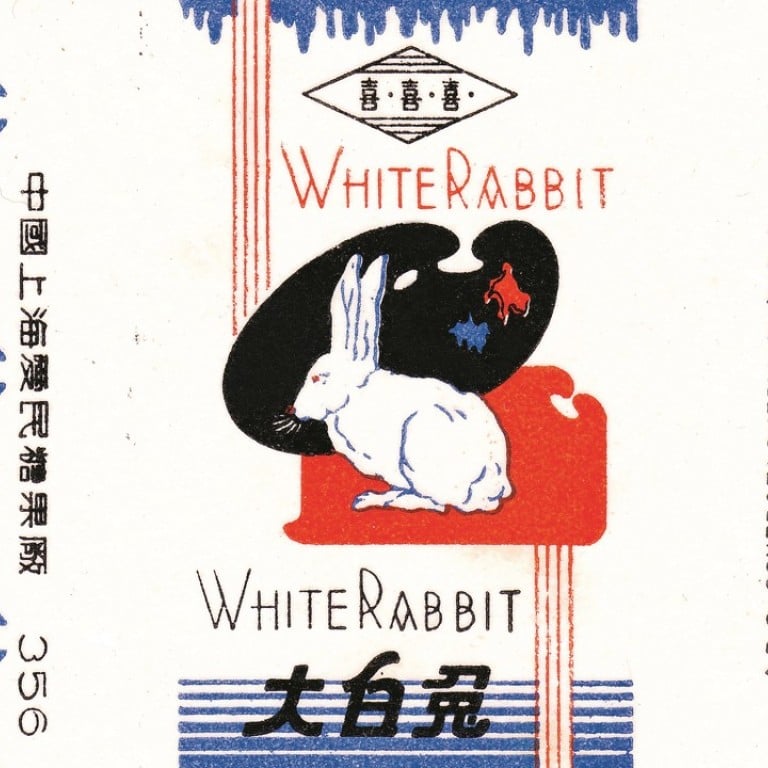

The milk candies now known as White Rabbit first appeared in the 1940s, and have been synonymous with Shanghai ever since. Their iconic branding and edible rice paper wrapping occupy a special place in the city’s collective memory and history.

For Shanghai native Terry Yang, these retro sweets are part of his family history too. The 23-year-old’s grandmother used to work in a store that sold the popular sweets in the 1970s, and would bring them home for her children, who in turn bought them for their own children.

“Every year, my grandparents still get plenty of White Rabbit candies for Lunar New Year. It’s a tradition in our family,” he says.

The Tiger Balm story: how ointment for every ailment was created, fell out of favour, then found new generation of users

German-born sinologist Maja von dem Bongart has lived in Shanghai for more than two decades, originally moving there with her young family. “White Rabbit has always been a part of my memory of Shanghai. My children still buy them when they are back here,” she says.

The sweets have also been adapted into new forms, with Shanghainese chef Tony Lu at the Mandarin Oriental even whipping up a White Rabbit ice cream for one of the luxury hotel’s seasonal menus.

“I have happy memories of eating White Rabbit myself when I was a child,” confesses Shen Qinfeng, marketing manager for the state-owned Guan Sheng Yuan Food Group, which manufactures White Rabbit Creamy Candy. “It wasn’t very common to have these treats then, and I can still remember the rice paper melting in my mouth.”

To show that his appetite for White Rabbit is not only nostalgia, Shen plunges both hands into his pockets and pulls out large fistfuls of the candies to pass around.

Although the famous art-deco-inspired wrapper is recognisable across China, not every fan of the candy will know that White Rabbit sweets did not initially feature a rabbit at all. Originally launched by private company ABC in 1943, and inspired by British creamy candy, the sweets were first called Mickey Mouse Sweets, and the wrappers featured the famed Disney rodent.

During the political upheaval of the 1950s, private companies such as ABC were nationalised and the use of Western imagery became politically sensitive. The rodent became a rabbit in 1959, and White Rabbit candies were officially launched.

In 1976, ABC (by then renamed Ai-Ming) was absorbed by the state-run Guan Sheng Yuan Food Co. Originally producing the sweets at Caobao Road in Shanghai’s city centre, Guan Sheng Yuan’s new factory opened in 2013 a few hours south of central Shanghai, in a development zone nestled amid rural farmland and streams in Fengxian district. The factory is hard to miss, not least because two enormous white rabbit figures peep out from behind the border hedge to greet guests.

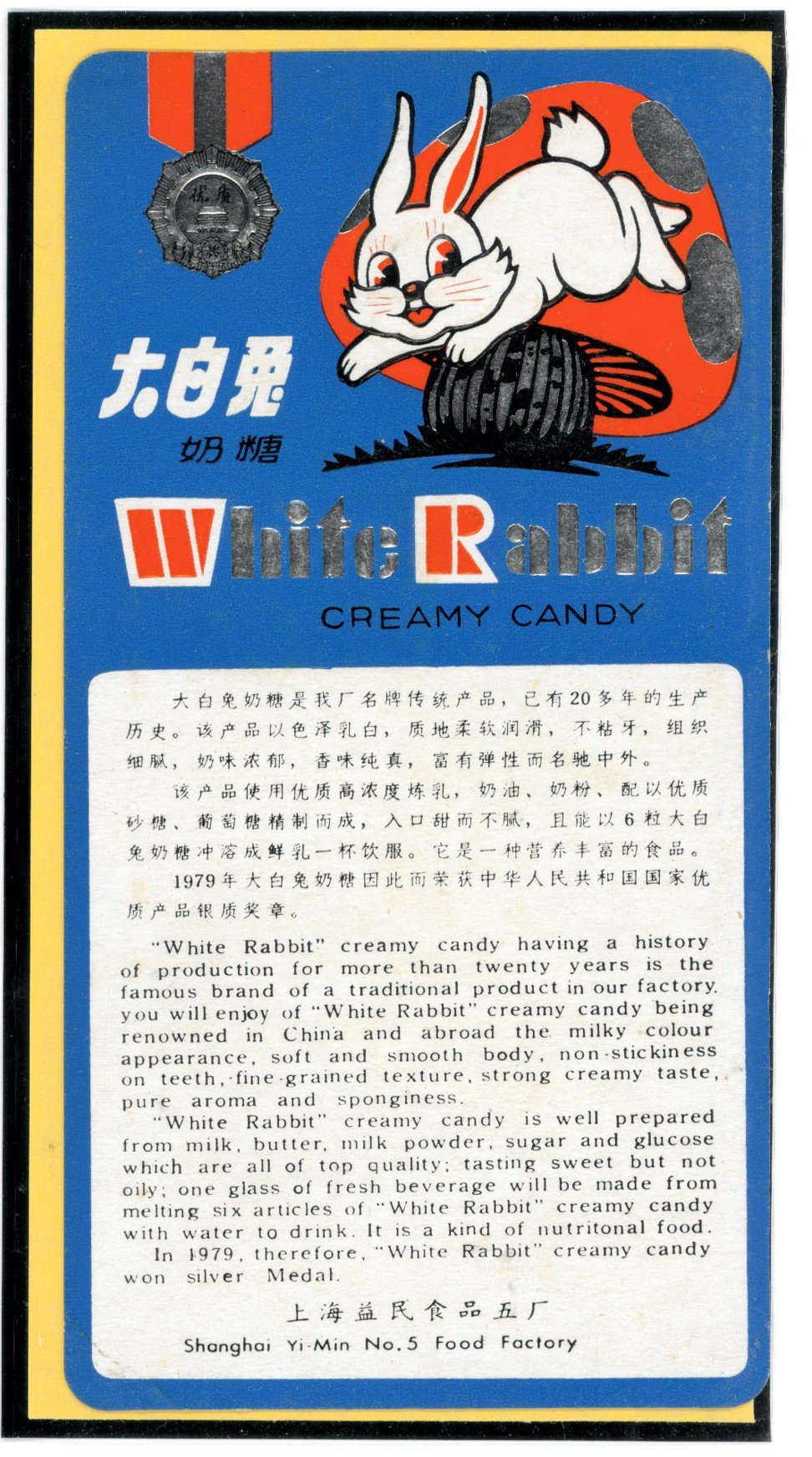

Inside, the sickly sweet smell of sugar from the factory’s long production line wafts up to greet visitors. More than 24,000 tonnes of the sweets are produced here every year by about 500 staff members, although the workforce doubles during the high season from October to February to meet demand. Across China, White Rabbit Creamy Candy accounts for about five per cent of all candies sold, and Lunar New Year, Mid-Autumn Festival, the week-long National Day holiday and Christmas are some of their busiest times.

For many staff, the brand is a lifelong love. Shen has been at the company for 15 years, while the company’s deputy general manager, Jiang Changyuan, has worked at Guan Sheng Yuan for 33 years. He says he has been treating generations of his family with the famous sweets on special occasions for years. Factory workers get bags of the candies to take home at Lunar New Year, and the conference room has bowls of different flavoured treats laid out for snacking executives.

“The brand has become so iconic in China because of its history,” says Shen. “After the launch of the new China, there was a lack of materials and ingredients, so White Rabbit was the pioneer in making these kind of milk sweets. It’s not just a kind of sweet – it’s a good memory of China in the past.”

White Rabbit sweets are also inseparable from China’s political history. In 1959, the candies were given out in the city as gifts for the 10th National Day of the People’s Republic. Former premier Zhou Enlai – who was said to always have a bag on his desk – gave White Rabbit candies as a gift to American president Richard Nixon during his historic 1972 visit to China. And in 2013, President Xi Jinping visited the new factory in southern Shanghai, and handed out the sweets to officials and children on a visit in the same year to Mongolia.

Before China’s economic opening up, White Rabbit completely dominated the domestic market. A limited production run meant demand always outstripped supply and, Shen says, buyers used to park outside the factory to stock up cars with the sweets, driving them to other provinces to sell on to consumers.

“The high point for the brand was in the ‘80s and ‘90s – those were really good times for White Rabbit,” Shen says. “Although China was opening up, a lot of brands from abroad had not yet entered the market, and White Rabbit was the main quality option at that time. If the consumers wanted to buy some sweets, White Rabbit would come to their minds first.”

But as Chinese consumers and tastes change, White Rabbit has found itself competing for attention in a busy and cosmopolitan market. Many imported sweets can now be seen on the shelves of Shanghai’s supermarkets and convenience stores, and the iconic rabbits have struggled to keep market share, leading the company to diversify its products.

“The biggest focus for us right now is to stick to White Rabbit’s tradition while also being innovative,” Shen explains. “Older people grew up eating White Rabbit, but the younger generation know the sweet because their parents, their grandparents like it. Younger children now have so many options for sweets and candies – our focus now is how to make White Rabbit appeal to the younger generation.”

Increasingly health-conscious consumers in China are also shifting away from too much sugar in their diets, particularly for their children. While the sweet was once thought to be a healthy option because it contained milk, parents are now better informed now about the health implications of sugar.

The brand was also hit by the country’s 2008 melamine scandal.

When more than 52,000 children were made ill by melamine-tainted dairy products in China, White Rabbit was listed among the many milk-based food products that were found to be contaminated with the chemical compound. British supermarket chain Tesco removed White Rabbit sweets from its stores, while food authorities in Australia, the US and Singapore issued cautions or recalls over the product. All this affected the brand’s reputation and sales.

Undeterred, the brand has been mounting a comeback during the past decade. White Rabbit now only uses imported milk powder from New Zealand to reassure consumers. In a bid to compete with imported brands, the company has introduced a variety of new flavours, including chocolate, peanut, red bean and yogurt. There are now more than 30 products in the White Rabbit brand line – although the classic flavour remains the bestselling sweet.

The brand is also finding more fans in international markets. Shanghai’s White Rabbits are now exported to more than 40 countries and territories, finding particular popularity in Southeast Asia, including Singapore, Thailand and Malaysia.

The sweets are also sold in the US and Europe. Exports only account for about five per cent of total sales, but Guan Sheng Yuan has ambitions to grow this.

As these retro sweets forge into new markets, new consumer groups and new tastes, balancing tradition and modernity will be the key challenge.

Made in Hong Kong: Eu Yan Sang’s 138-year journey making traditional Chinese medicine has been a bumpy one

“White Rabbit is not only a sweet, but a symbol of happiness. It’s a bridge between different people – between guests, and family members,” Shen concludes. “Nowadays, society is very crowded and busy. White Rabbit candy can take you back to the peaceful days, and provide happy and calm moments.”

Additional reporting by Wu Tong