Snake restaurant in Hong Kong to close after 110 years, marking end of an era

Family-run She Wong Lam in Sheung Wan was hugely popular, with actor Stephen Chow a regular customer. But its snake handler is nearly 90, and no one in the family wants to continue the business

Family-run She Wong Lam was hugely popular in the 1960s and 1970s, but with no one from the family’s younger generation keen to continue the business of looking after snakes and preparing them for soup, the restaurant will close its doors on July 15.

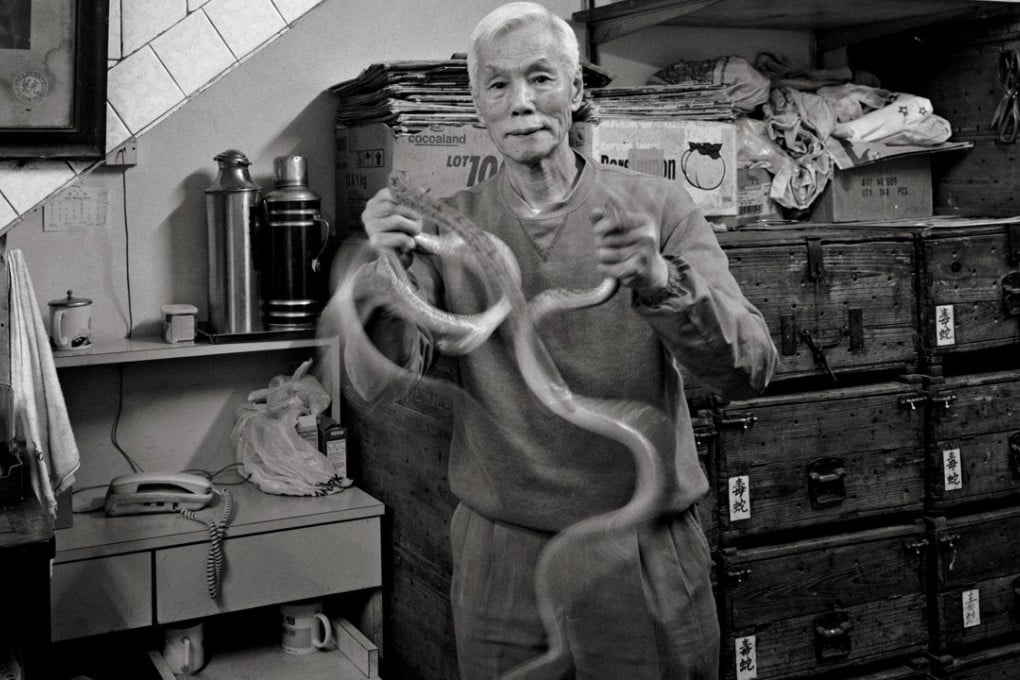

“Master Mak is almost 90 and he is the boss of the shop. He has worked for four generations of our family,” Lo says by phone from Vancouver, Canada. “Since my grandfather passed away, my father [Lo Yip-wing] didn’t know much about the snake business and I know even less,” he says.

His family trusts Mak but are unfamiliar with the shop’s other employees, making it hard for them to continue the business, he explains.

Lo says the date for closing She Wong Lam was chosen by his uncle and father, the latter now in an old people’s home in Hong Kong. Lo, an accountant, and his younger sister have lived in Vancouver since he was about eight years old and he does not intend to return.

“It’s very difficult to find people to work in this particular industry. It’s not for everyone,” Lo says.