Winemaking sisters in Thailand face tight restrictions on alcohol sales that favour billionaire drinks producers

- Mimi and Nikki Lohitnavy have battled Thailand’s tropical climate, chased off elephants from their vineyards and won over a sceptical public

- Now they must overcome restrictive Thai laws on alcohol sales that favour its duopoly of drinks giants if they are to continue making their award-winning wines

Sisters Mimi and Nikki have battled Thailand’s tropical climate, chased off elephants from their vineyards and won over a sceptical public to their award-winning wine. Now they’re taking on alcohol laws that critics say benefit the kingdom’s billionaire drinks monopolies.

03:04

Thai wine sisters say liquor laws are holding back the industry’s post-pandemic recovery

Rows of syrah, viognier and Chenin Blanc grapes stretch across the 16-hectare (40-acre) GranMonte Estate in the foothills of Khao Yai National Park.

The elevated terrain, three hours outside Bangkok, provides fertile ground for grapes, and an escape from city life; a rust-coloured guest house could be pulled straight from a Tuscany tourism advert.

As they snap selfies in between the vines, visitors run into Nikki Lohitnavy, 33, who studied oenology in Australia and now steers the science behind each bottle.

She painstakingly experiments with grape varieties to see how they respond to the climate – it takes at least six years to see if a decent wine will emerge from the ground.

The plot of land was once a cornfield, but their father, Visooth, transformed the terrain into trellised vines, and as a teenager Nikki joined him in the fields.

Younger sister Mimi was not interested in viticulture, but today she heads the label’s marketing, calling it her “mission to put Thai wine into the market”.

Online wine tastings and karaoke pairings, anyone?

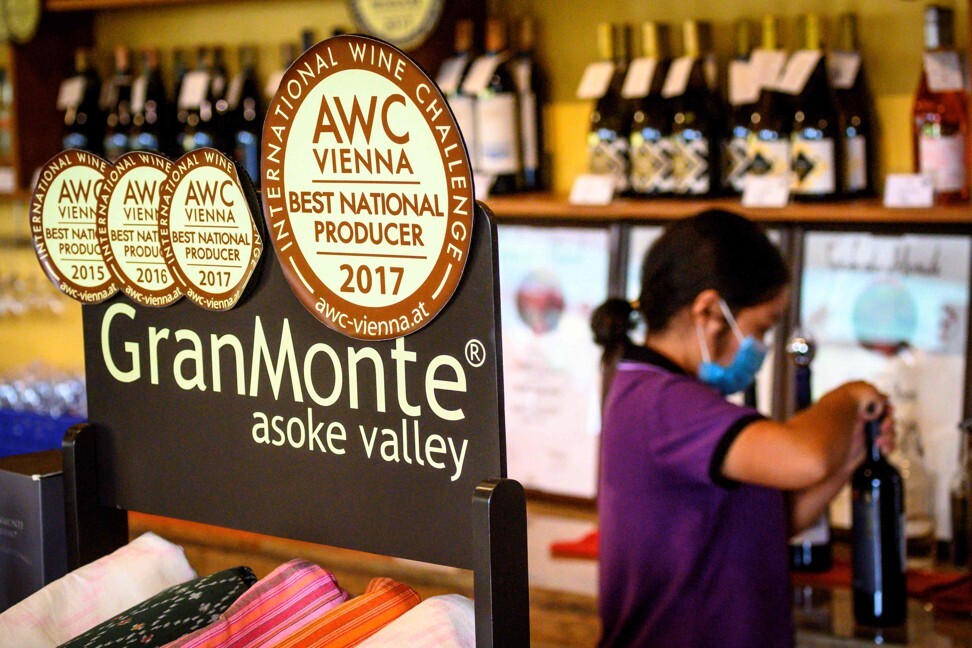

The kingdom’s wine remains an outlier – grapes grown in warmer temperatures tend to produce tannic wines, something that seasoned drinkers eschew. But after more than two decades in business, GranMonte is gaining recognition.

“Winemakers around the world want to know what we do here because the climate is changing, so they have to adapt to warmer temperatures and higher rainfall in their regions too,” Nikki says.

Its proximity to a national park also sees hungry elephants occasionally trespass through their vineyard, prompting calls from the sisters to rangers for help.

Despite the gains, the long-term future of the GranMonte wines is clouded by the kingdom’s heavily restrictive alcohol laws. A devoutly Buddhist kingdom, Thailand also has the highest alcohol consumption per person in Southeast Asia, according to the World Health Organisation.

Rules that include high import taxes on alcohol, with hefty fines for breaches, and a licensing culture where bars require friends at local police stations, can make drinking a complicated business.

Then there’s the 2008 Alcoholic Beverage Control Act, a law forbidding the display of alcohol logos on products, as well as any advertising that could “directly or indirectly appeal to people to drink”.

This is aimed at controlling consumption, but in effect clips the wings of small producers who do not possess the same reach to customers as established brands.

“I can’t show clearly a bottle of my wine, I can’t post on social media what the wine tastes like, or how or why it’s good,” says Mimi, who worries that their website might fall afoul of the law.

Critics say the law has always been unevenly enforced, allowing big players in the drinks industry to cement their brand recognition by spraying their logos via non-alcoholic drinks like soda water on giant billboards and public transport.

The market leader – Thai Beverage – makes the ubiquitous Chang lager. The firm is owned by the Sirivadhanabhakdi family, the kingdom’s third-richest with US$10.5 billion in wealth according to Forbes, and their portfolio includes massive downtown Bangkok real estate projects and hotels.

Together with Boon Rawd Brewery – which produces Singha and Leo – the duopoly are unrivalled in reach and capital. Neither responded to multiple requests for comment.

Thailand’s alcohol laws are uncharacteristically responsive to changes in drinking culture. Online alcohol sales – which surged during the pandemic lockdown – are now in the regulators’ crosshairs, potentially closing down another revenue route for small alcoholic-drinks producers.

GranMonte lost 30 million baht (US$964,000) in three months during the shutdown – and Mimi says its recovery will be further hampered if, as believed, a ban on selling alcoholic drinks online comes in.

Nipon Chinanonwait, director of the Ministry of Health’s Alcohol Control Board, rejects criticism that established giants are given an unfair advantage. “Both big and small companies face the same procedure,” he says. The ministry insists the laws are there only to prevent underage drinking.

The sisters have teamed up with dozens of small-scale craft brewers, importers and bars to petition the government to rescind the advertising law, and to halt the impending ban on online alcohol sales.

“People cannot live like this,” says brewer Supapong Pruenglampoo, who hid his Sandport Brewing Facebook page from public view in fear of a crackdown. “In these Covid times, [the fines] are impossible to pay,” he says.

But in an unequal kingdom, any efforts to change the monopoly culture are bruising.

It’s “a reflection of how Thailand operates”, says Mimi. “The lawmaking, the enforcement and everything surrounding it is to benefit the small group of people holding most of the wealth in Thailand.”

As Nikki tastes their recent batch of syrah wine, kept in imported barrels, she says the challenges to start were numerous. Now they are working to stay on top.

“It’s our passion – we like it so we do it,” she says.

.png?itok=arIb17P0)