Restaurant loved by Bruce Lee, famed for its roast pigeon and featured in Hong Kong films, looks to the future

- Owner of the Lung Wah Hotel restaurant in Sha Tin reflects on the good old days when martial arts film star Lee was a regular customer, and look to the future

- The Chung family plan to expand their offering to include Western food and open a music school on the premises

Hong Kong’s Lung Wah Hotel, famed for its roast pigeon, is in a compound tucked into a hillside just steps from the railway track in Sha Tin new town.

Built in 1938 as a rural retreat, Lung Wah was turned into a combined hotel and restaurant in 1951. The guest rooms were closed in 1985, but the restaurant soldiered on and the founding Chung family plan to celebrate its 70th anniversary next year by taking it in a new direction.

“We have to move with the times and attract a new clientele, while staying loyal to our traditional customers,” says Vincent Chung, 27, who now runs Lung Wah with his mother, Ma Lai.

“What we have in mind is a separate restaurant which will serve Western food, and a music school aimed at budding violinists and pianists from Sha Tin and further afield. Of course, our plans depend on what happens with the coronavirus, but we’re very confident.”

Lung Wah, whose boxy architecture and brightly coloured walls earned it the nicknames “Square House” and “Red House”, has a chequered past. Not long after the official opening in 1939, the owners – Vincent’s grandparents, bullion dealer Chung Sau-cheung and his wife, Chan Yun-wah, who ran a soap factory – had to move out because Lung Wah was requisitioned by the Japanese army.

Turning it into a 10-room hotel and restaurant in the post-war years, and billing it as “The Peninsula of Sha Tin”, proved to be an astute business move. In the 1950s, Sha Tin – which had once been so fertile that rice was grown there especially for the Chinese emperor – was still a valley with a single railway line running through it. Happily removed from the urban areas of Hong Kong and Kowloon, it became a popular weekend break for city dwellers.

Served with a side of nostalgia, Hong Kong’s original fusion food

Lung Wah was the first real hotel in the area, and its pigeons – served up for many years by master chefs So Chan and So Qiu – were an additional draw.

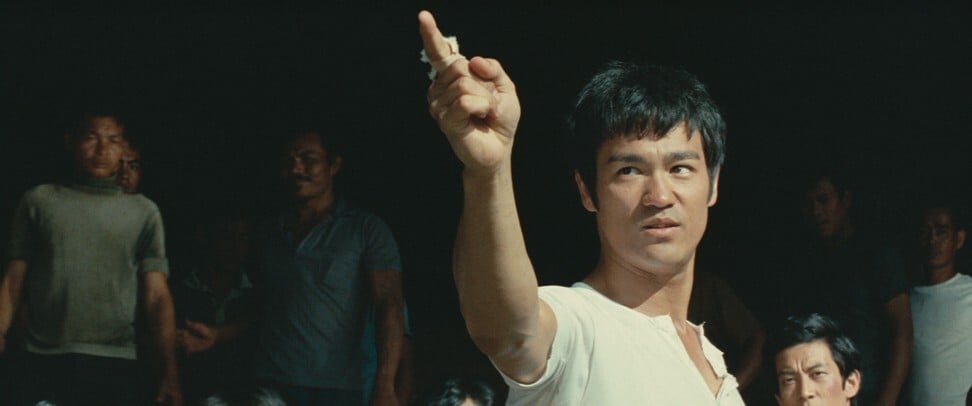

Newspaper magnate Louis Cha Leung-yung and martial arts film star Bruce Lee were among the many well-known faces who used to drop by with friends and family for a meal. Lee stayed at the hotel for a time during production of his blockbuster The Big Boss. While strictly a rural hideout, it was certainly good for Lung Wah’s takings. More recently, Lung Wah made a brief appearance as a backdrop in Pang Ho-cheung’s 2001 dark comedy You Shoot, I Shoot.

Other celebrities who showed up from time to time included movie stars Josephine Siao Fong-fong, Connie Chan Po-Chu and Cheung Wood-yau. It was a haunt for the big names of Cantonese opera too, such as Hung Sin-nui and Yam Kim-fai.

“More middle-class and wealthy people started venturing into the New Territories in the 1950s and ’60s,” says Cho Cho-man, who conducted a study of Lung Wah – “Consuming Nostalgia” – for City University’s department of Chinese and history.

“Lung Wah was a landmark – the first two-storey building in Sha Tin – and its huge sign acted as a come-on. The hotel was selling more than 5,000 [roast] pigeons on a good day, more than any other restaurant in Hong Kong. So going there for lunch or dinner and then settling down for a mahjong session was a big day out.”

Lung Wah’s signage also attracted unwanted visitors. “Illegal immigrants who’d sneaked aboard the Kowloon-bound train were told to keep an eye open for the Lung Wah sign,” Cho explains. “As soon as they saw it, they knew their journey was almost at an end and had to jump off and make themselves scarce. So it wasn’t just a landmark for day trippers.”

As Sha Tin was developed over the years, Lung Wah’s prominence gradually diminished. High-rises rose, fields disappeared beneath tarmac, and the government took over the land that had been the hotel’s car park, discouraging overnight guests.

The restaurant was generating more revenue, so in 1985 the Chungs decided that their days of playing hotelier were over. While it is still called the Lung Wah Hotel, nowadays it serves only food and drinks.

Much of the pleasure of dining at Lung Wah lies in its mildly eccentric location. Sidestep the bland building that is the HomeSquare mall hard by Sha Tin MTR station, and a rough concrete path leads northeast past village houses alongside the railway.

After a few hundred metres, visitors can see Lung Wah’s bold red characters and a flight of steps hung with scarlet lanterns. The shabby chic decor surprises at every turn. Towering flame trees partially hide Sha Tin’s concrete towers; a small flock of pigeons and a trio of peacocks caw in cages guarded by fibreglass statues of what look like a greying version of Sesame Street’s Big Bird and a jolly Swedish chef.

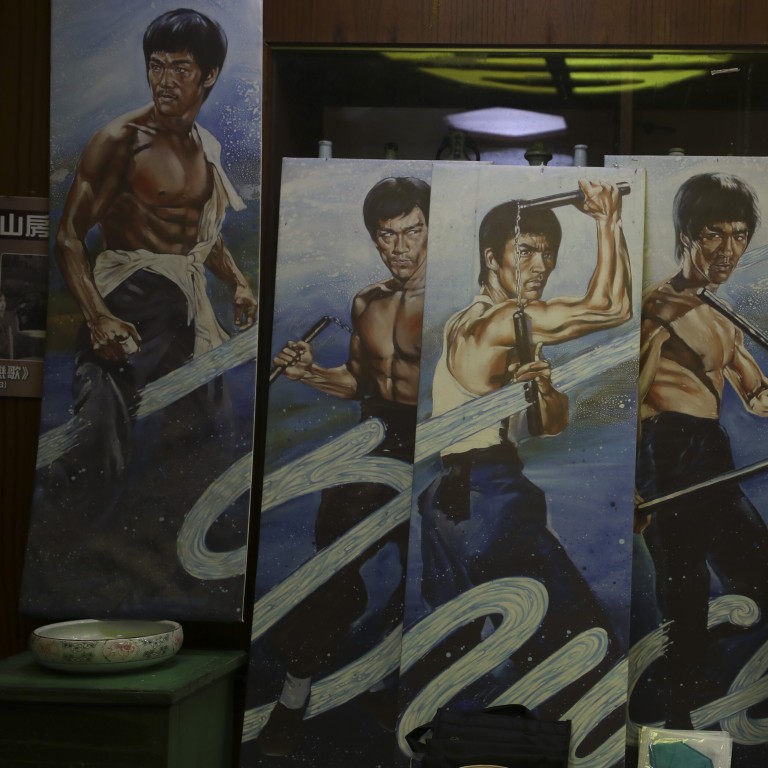

The restaurant itself is an exercise in extravagant decor: golden table cloths and chair covers, terracotta tiles on the floor, arched windows, lazy ceiling fans, carved wooden screens, and walls hung with quirky oil paintings and black-and-white photos of the former Kai Tak airport and Hong Kong cinema stars in their glory days. The superstars includes Lydia Sum and martial arts star Lee, the latter in his famous fighting pose.

Lung Wah’s menu has altered only a little over the past seven decades, and deep-fried pigeon still ranks highly, followed by birds poached in soy sauce, marinated, accompanied by egg and bird’s nest, or minced with abalone and bamboo shoots.

Tofu – with black mushroom sauce, stuffed with minced pork or given a Sichuan-style boost – has long been popular with diners who prefer something other than pigeon.

“Our chef, Cheung Chan-wai, has been with us since he was 14. He’s in his 50s now, so you might say he’s pretty experienced,” Chung says.

“Some things have changed, though. Our tofu used to be handmade here in Ha Wo Che village by Uncle Lee, and he would deliver it fresh every day, carrying it in on a pole yoked across his shoulders. He’s since retired, and his son didn’t want to continue the business, so we get our tofu from a mainstream supplier now.

I have so many happy memories of Lung Wah – we’d always celebrate our birthdays and big festivals here – and the new restaurant and the music school will take us into a brand new era

“It’s the same with our pigeons. We used to breed them ourselves, but the bird flu outbreak in 1997 put a stop to that, so we import them from three different suppliers in Shenzhen. The quality’s still absolutely top-notch – we serve them when they are fully grown at 25 days old – but it’s not quite the same as ‘home-grown’.”

“The only damage was to an outbuilding. The restaurant was not affected at all, but it did start me thinking that now is a good time to consider how we do things,” Chung says.

“We’re famous for pigeon, but by opening a Western-style cafe we can broaden what we offer, and attract more guests. And the music school will be in a separate building so we are making use of our assets during the times when the restaurant is quieter.”

Chung says he plays the violin and piano, so would like to see the younger generation have the opportunity to learn too, especially in such peaceful surroundings.

“My earliest memory of Lung Wah – and I must have been about five years old – is the peacocks. I could tell they were birds, for sure, but when the male spread his tail feathers it was like some incredible conjuring trick. I’d watch it for ages,” he says.

“I have so many happy memories of Lung Wah – we’d always celebrate our birthdays and big festivals here – and the new restaurant and the music school will take us into a brand new era,” Cheng adds.