Advertisement

What Google ban? How to get Huawei phones working with US apps and services like Google Maps and Instagram

- The US government ban on Huawei working with American companies is not as dire as it sounds for people wanting a new Huawei phone

- Here are easy ways to get things like Google’s search and maps, Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, YouTube and Netflix onto Huawei phones

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

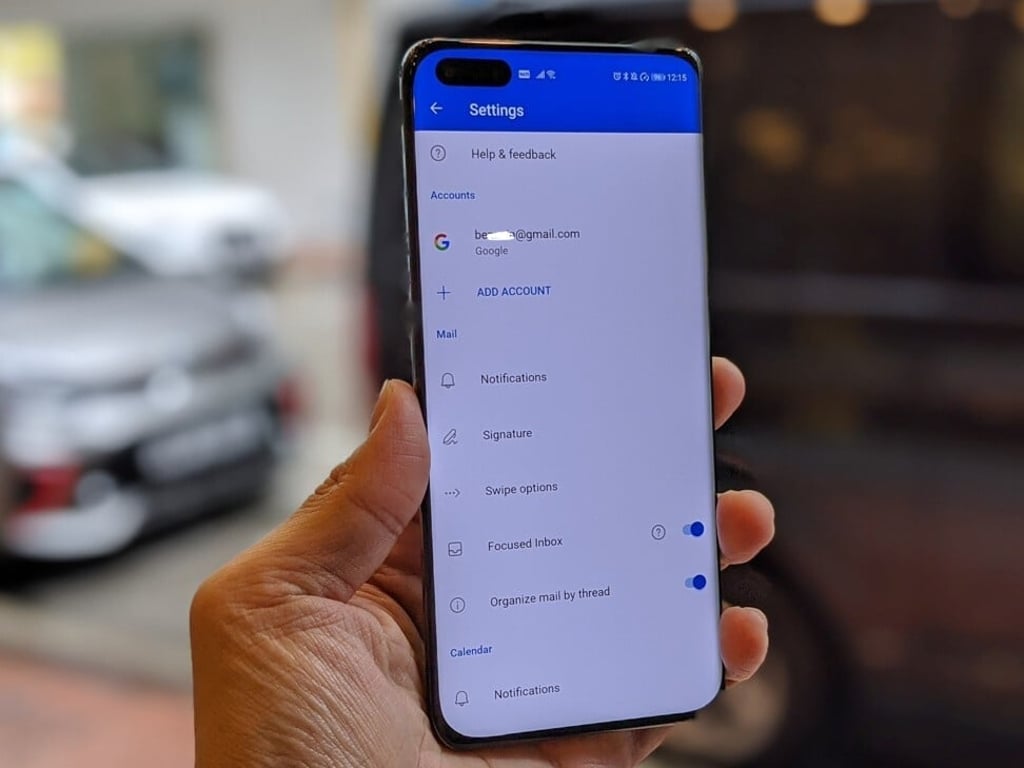

So you’re in the market for a new smartphone. You’ve heard plenty of great things about Huawei’s recent releases, which have cutting-edge hardware such as cameras that can see in the dark or a screen that folds in half. But you’ve also heard that the US government has banned Huawei from working with American companies, which means no Google services on Huawei phones.

So you look elsewhere because, like most people outside mainland China, your most widely used apps and digital services are American: Google’s search and maps, Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, Twitter and so on. And did you not also hear something about Huawei being forced to build its own OS as an alternative to Google’s Android?

The situation actually isn’t as dire as this for Huawei – or for its customers.

Advertisement

Huawei phones – even recently announced ones like the Huawei Mate XS and P40 Pro – can run all the American services we mentioned above. And Huawei’s HarmonyOS, which was introduced last summer, is for the Chinese tech giant’s enterprise and home ecosystem business.

Advertisement

Every Huawei rep who has spoken on record over the past six months has insisted the company’s phones will not stop running Android. And there’s nothing the US government can do about that.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x