Thai doctors battle cancer-causing raw fish dish in country’s northeast

The pungent and cheap meal, koi pla, served in rural Thailand can cause lethal liver cancer; up to 20,000 people a year are dying. A surgeon who saw it kill his own parents is testing villagers and urging them to change their diet

It wasn’t until he got to medical school that Narong Khuntikeo finally discovered what caused the liver cancer that took both of his parents’ lives – it was their lunch.

Like millions of people from across the rural northeast of Thailand, his family regularly ate koi pla, a local dish made of raw fish ground with spices and lime.

The pungent meal is quick, cheap and tasty, but the fish is also a favourite feast for parasites that can cause a lethal liver cancer which kills up to 20,000 people in Thailand annually. Most hail from the northeast; a large, poor region known as Isaan that has dined on koi pla for generations and now has the highest reported instance of the Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) – bile duct cancer – in the world.

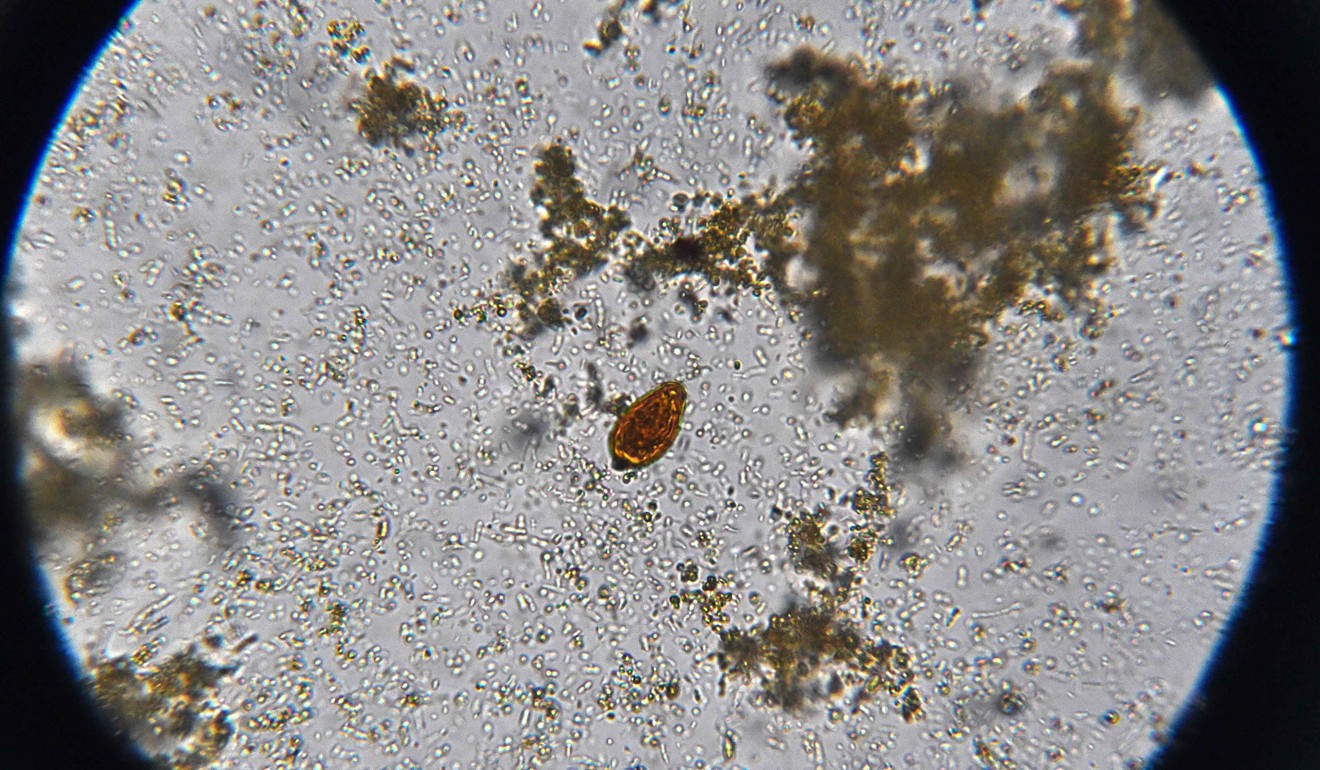

One of the major causes of CCA is a parasitic flatworm (or fluke) which is native to the Mekong region and found in many freshwater fish.

Thousands line up to swallow live fish for asthma cure in bizarre Indian treatment

Once eaten, the worms can embed undetected in the bile ducts for years, causing inflammation that can, over time, trigger the aggressive cancer, according to the World Health Organisation.

“It’s a very big health burden around here … it affects families, education and socioeconomic development,” says Narong, who became a liver surgeon to battle the scourge. “But nobody knows about this because they die quietly, like leaves falling from a tree.”

After seeing hundreds of hopeless late-stage cases on the operating table, Narong is now marshalling scientists, doctors and anthropologists to attack the “silent killer” at its source.

I’ve never been checked before, so I think I will probably have it [liver cancer] because I’ve been eating [koi pla] since I was little.

They are fanning out across Isaan provinces to screen villagers for the liver fluke and warn them of the perils of koi pla and other risky fermented fish dishes.

But changing eating habits is no easy task in a region where love for Isaan’s famously chilli-laden cuisine runs deep.

Many villagers are shocked to hear that a beloved dish passed down for generations is dangerous. However, others remain wedded to the convenience of a thrifty lunch they can whip up using fish caught in the ponds that border their rice paddies.

“I used to come here and just catch the fish in the pond … it’s so easy to eat raw,” says Boonliang Konghakot, a farmer from Khon Kaen province. Since learning of the cancer link he has started frying the mixture to kill off the parasite – a method doctors recommend.

Yet not everyone is as easily swayed, according to Narong and his team. Many villagers complain that cooking the dish gives it a sour taste.

Others simply shrug off the dangers and say their fate has already been fixed – a common belief in the Buddhist nation where karma can dictate decisions.

“They’ll say: ‘Oh well, there are many ways to die’,” laments Narong. “But I cannot accept this answer.”

Trump’s Mar-a-Lago eateries hit with food safety violations

When it comes to changing eating habits, health officials are pinning their hopes on the next generation, targeting children with a new school curriculum that use cartoons to teach the risks of eating fish raw.

For the elderly, the target is to catch infections before it’s too late.

Narong and his team have developed urine tests to detect the presence of the parasite, which has infected up to 80 per cent of some Isaan communities.

They have also spent the past four years trucking ultrasound machines around the region to examine the livers of villagers who live far from public hospitals.

The initiative started as research at Khon Kaen University but received full government backing last year, putting it on Thailand’s national agenda.

How to wipe out mosquitoes and eradicate malaria? A mutant fungus may hold the answer

“I’ve never been checked before, so I think I will probably have it because I’ve been eating [koi pla] since I was little,” says 48-year-old Thanin Wongseeda, one of 500 villagers lining up for a recent screening in Kalasin province.

The group ticks off a series of high-risk factors: they were over the age of 40, had a history of eating raw fish and had family members with the cancer.

A third of them showed abnormal liver symptoms and four were suspected to have cancer.

Thanin was one of the lucky ones, emerging from his ultrasound with a look of relief.

“I don’t think I will eat [koi pla] raw any more,” he says. As for his neighbours?

“They will not quit it easily.”

.png?itok=arIb17P0)