Made in Hong Kong: Eu Yan Sang’s 138-year journey making traditional Chinese medicine has been a bumpy one

Despite years of family strife, the murder of the founder’s wife by her brothers-in-law and a takeover by a Singapore investment group, traditional Chinese medicine maker Eu Yan Sang has survived and flourished as a Hong Kong icon

After an 80km ferry ride south from Penang, then days on a wooden boat up the Perak River and a tedious trek through the jungle, Eu Kong, with his wife and baby, arrived in Gopeng, a remote but prosperous tin mining town in what is now Malaysia.

Eu had been sent from Foshan, in China’s southern Guangdong province, to British Malaya by his father, a feng shui master who believed his family would prosper in Southeast Asia. After failed ventures in a bakery and a textiles dyeing business in Penang, Eu moved inland to join thousands of Chinese miners on a tin rush.

When Eu saw the condition of his fellow Chinese, many addicted to opium, he decided to start selling traditional Chinese herbal medicine made using the ancient recipes that had been passed down through Chinese culture.

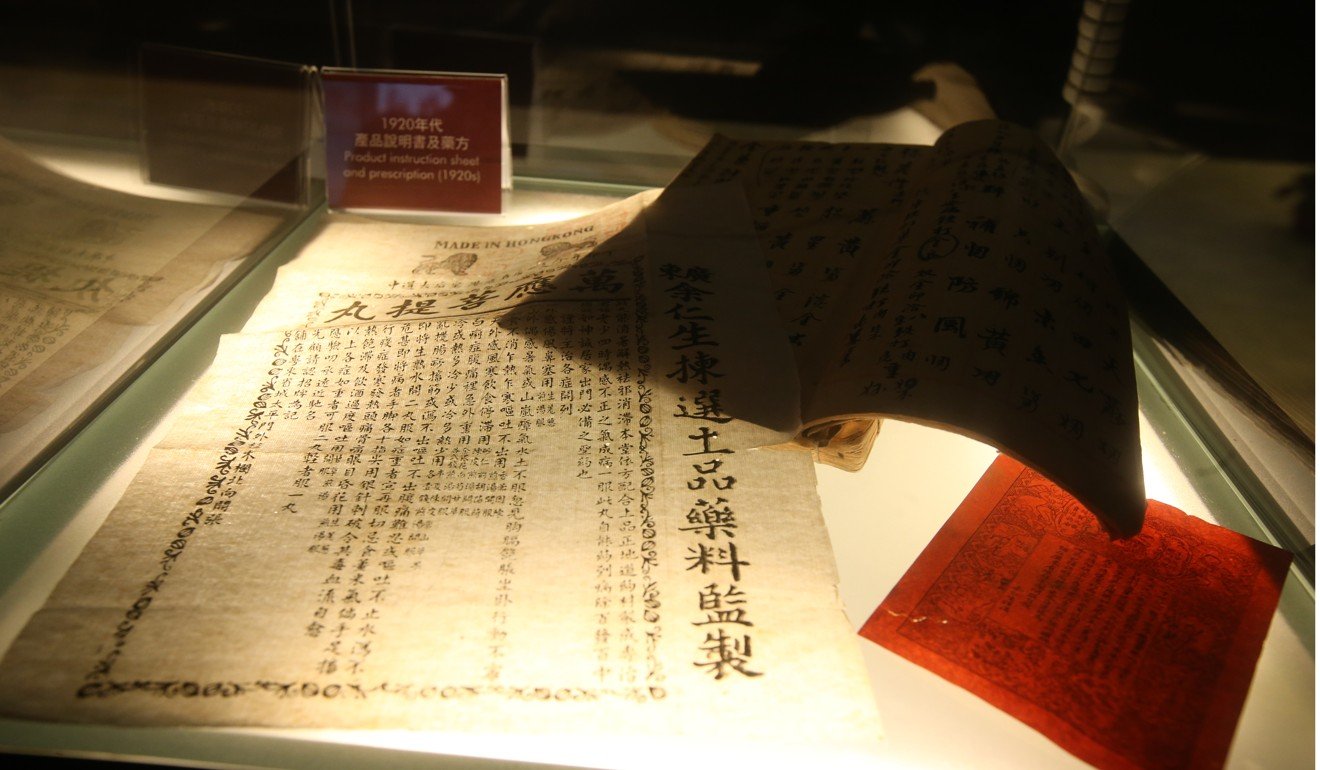

It was 1879, and that humble shop in the Malayan countryside was to be the seed of what is now Eu Yan Sang International – a traditional Chinese medicine company and iconic Hong Kong brand with 248 retail outlets and 34 clinics in Hong Kong, Macau, mainland China, Malaysia, Singapore, Australia and farther afield. Its most popular products are Bo Ying, a soothing remedy for coughing babies, and Bak Foong Pills, which help alleviate menstrual symptoms.

The saying “shirtsleeves to shirtsleeves in three generations” implies family businesses cannot survive for more than three generations. But Eu Yan Sang, which celebrates its 138th anniversary this year, is an exception. It is now in the hands of fourth-generation family members Richard Eu Yee Ming and Robert Eu (and institutional shareholder Temasek Holdings & Tower Capital).

Despite the longevity, the ride has been far from smooth. Riven by family strife, a corporate takeover and drama in the boardroom, the history of the company and the Eu family reads like the plot of a soap opera.

The official line is that Eu Kong opened the Yan Sang Medicine Shop (Yan Sang meaning “benevolence and life”) only to help the coolies. A 2009 biography by Ilsa Sharp about his son, Eu Tong Sen, reveals another side of the story. Path of the Righteous Crane recounts how Eu Kong also gained from the miners’ bad habits by collecting taxes on opium, gambling and alcohol for the British colonial government.

Either way, Eu Kong was a savvy entrepreneur. He used his earnings to buy land that was rich in tin deposits, and soon became a prominent businessman, supported by his second wife Mun Woon Chang, a well-connected Nyonya (female Malacca Strait-born Chinese).

Despite Eu’s success, his enjoyment of it was to be short-lived – a disease, probably smallpox, claimed his life at the age of just 37. All his possessions went to Mun, triggering the envy of Eu Kong’s two gambling addict brothers, who murdered her by lacing the family dinner with poison during a visit to China.

Sixteen-year-old Eu Tong Sen narrowly escaped death and inherited his father’s enterprise. Toughened by the traumas of his early life, he went on to become one of the richest men in Southeast Asia in the early 20th century, owning tin mines, rubber plantations, properties and even a bank.

Despite his more lucrative ventures, Eu did not forget the Yan Sang business. In the 1910s, he added the family name to the company’s chop and opened new branches in Singapore, Kuala Lumpur, Canton (now Guangzhou) and Hong Kong.

The shops played a crucial role among the Chinese diaspora, connecting overseas workers with their families at home. Shop clerks read out letters to the illiterate and wrote replies, and sent their hard-earned cash home for them. Profits earned through remittances surpassed that of selling medicine, and cemented the company’s reputation for trustworthiness among the Chinese community.

Homegrown Hong Kong: the wholesome story of Vitasoy

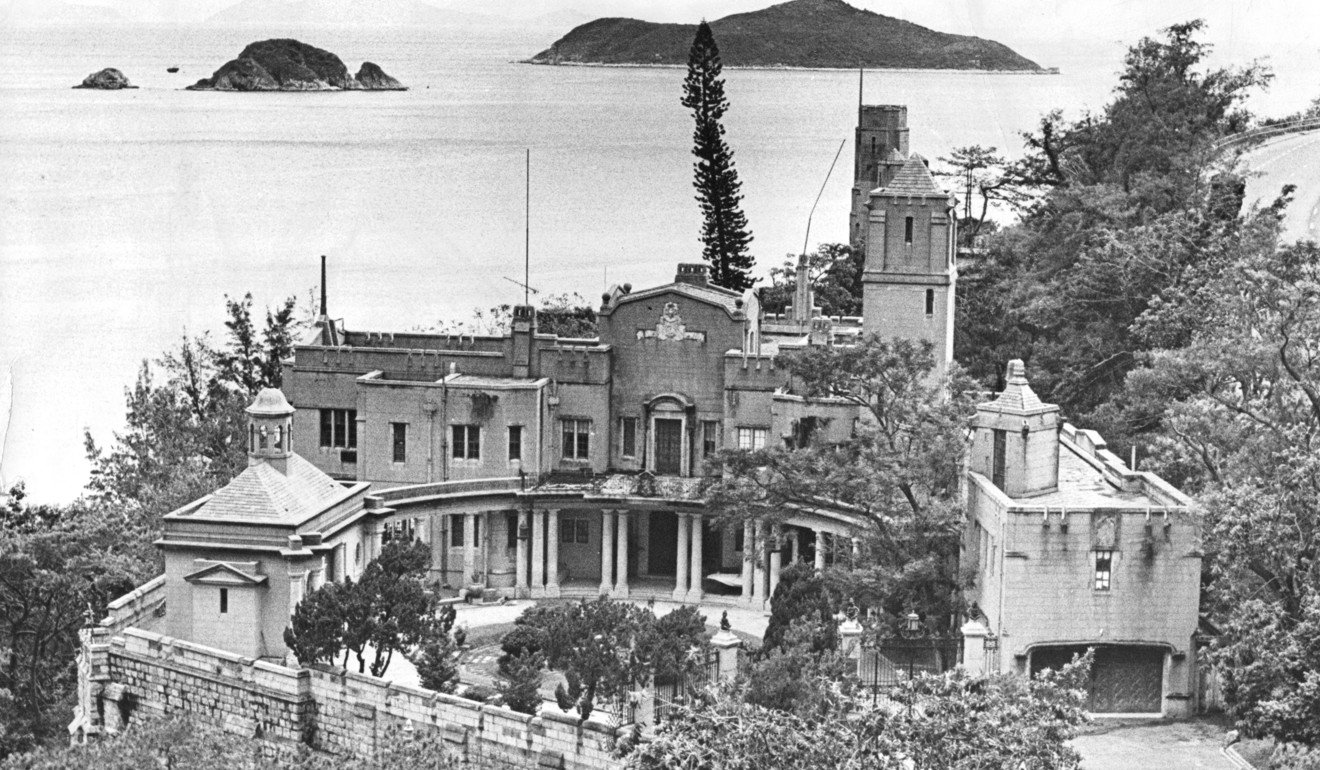

In 1928, the Chinese in Malaya suffered a backlash after demanding more say in the country’s governance. Eu’s company was threatened with a boycott and he moved his base to Hong Kong. Here, he put down roots as his business flourished, building three stately mansions with beautiful gardens and exotic pets, including peacocks and even a panda. He reportedly hosted large banquets attended by the city’s elite.

Despite his prosperity, he made a decision late in life that would threaten to tear his empire apart. Eu Tong Sen had four wives, 13 sons and 11 daughters, and divided his fortune, including Eu Yan Sang, equally among his sons. The business thereby became too complex to govern after he died in 1941, and by the 1980s, most of Eu Tong Sen’s assets had been sold off. Eu Yan Sang remained, struggling under a divided leadership.

The fact that we call it ‘traditional Chinese medicine’ is already a challenge. Why not just call it ‘Chinese medicine’? The challenge for me is trying to change the narrative

It could have been the end of Eu Yan Sang. But in 1989, eager to revive the family business, Richard Eu Yee Ming, a great-grandson of Eu Kong, left his banking job to take the helm of the company. He was soon put to test. Other family members sold their shares to Singapore-listed property and investment group Lum Chang, enabling it to stage a takeover. Luckily for Richard Eu, he was kept on as an general manager.

“No one saw it coming,” says his son, Richie Eu Zai Qi, who recalls how stressful that time was for his parents.

Eu Yan Sang twice became a public company. It listed on the Hong Kong stock exchange in 1992, which enabled Richard Eu and his cousin Clifford Eu to regain family control by buying back shares and consolidating disparate branches into one holding company. They took the company private again in 1996, then listed it on Singapore’s exchange in 2000. In May last year, Eu Yan Sang became a private company again.

Richie Eu, who is managing director of subsidiary Eu Yan Sang (Hong Kong) and a member of the fifth generation of the family to be involved with the business, is determined that the old company modernises and remains relevant in a fast-changing world. The company now practises “responsible ownership”, he says. “You have to separate the management from the ownership,” he adds, citing his father’s business philosophy.

Alice Wong Suet-ying, chairman of the same subsidiary, is a product of that policy. “[Eu’s] father believes familial ties should not be the main factor,” she says. “Anyone with capability should be able to join the management.”

Wong, who was approached to join the company in 1993, is frank about her initial reluctance. “I was an accountant in the finance sector. I thought that if I wanted a better career path, I should join an international corporation. Traditional Chinese medicine was considered a sunset industry with little hope,” she says. Others warned her about the muddy waters of family businesses.

“For the first month, I wanted to turn back every time I got to the MTR station,” Wong admits, but those feelings quickly dissipated as she took on missions to modernise the company. Although she was the only woman in the company’s higher echelons, she soon proved she was as capable, if not more so, than her male colleagues.

Yu Kwen Yick chilli sauce: a Hong Kong classic

Within months, she had computerised the company’s accounting system and recognised the importance of validating its products. Working with universities and researchers, Wong sent teams to mainland China to collect and document ingredients used in the company’s products, a painstaking process that is still ongoing. She commissioned studies on the mechanisms and effects of each medicine, despite facing internal objections for revealing the formulae.

“We need to find a scientific way to prove the [benefits of] Chinese medicine. And we need to communicate that with the current and future generations through the modern language of science,” Wong says, pointing to a stack of encyclopaedias of Chinese medicine published by Eu Yan Sang.

The next step is to make that information available on digital platforms, Richie Eu says. “All the great stuff done, in terms of manufacturing, herb-sourcing, hasn’t been communicated very well. My generation of consumers needs validation and … accessibility.”

To appeal to younger consumers, Eu Yan Sang has modified its product packaging. Its herbal medicines, which used to be sold in the form of big balls (from which customers would pinch off bits to swallow) are also now sold as small pills, granules and capsules, so they are easier to administer.

Richie Eu admits a lot more needs to be done to convince younger consumers of the efficacy of Eu Yan Sang’s remedies. “The fact that we call it ‘traditional Chinese medicine’ is already a challenge. Why not just call it ‘Chinese medicine’? The challenge for me is trying to change the narrative,” he says.

Noodle maker Cheung Wing Kee: a Hong Kong success story

Wong insists that despite historic links to Southeast Asia, Eu Yan Sang is a Hong Kong company.

“Just like how people think of Germany when they think of cars, or associate Japan with electronics, I want people to think of Hong Kong when they think of traditional Chinese medicine – and think of Eu Yan Sang when they think of Hong Kong.”