Why traditional Chinese and Indian ayurvedic medicine can’t compete with Western drugs

Traditional systems are more focused on prevention and balance, while the West seeks to cure diseases and relieve symptoms with profitable medicines. A medical sociologist and author talks about the future for TCM and ayurvedic

For most of today’s 7.5 billion people, traditional medicine remains an integral part of their lives. That is despite the continuing expansion of an already formidable modern health care system built on the principles of Western science and market forces.

In Asia, home to 60 per cent of the world’s population, there is a deep-rooted belief that traditional medicines hold secret cures and knowledge that Western sciences have yet to – and may never – understand and explain.

Some of that belief is undoubtedly based on ignorance, superstition or misplaced cultural loyalty, says medical sociologist Mohamed Nazrul Islam. But to dismiss it entirely as blind faith would mean the end of all inquiry into ancient knowledge, and negate the value of research published over thousands of years.

Traditional medicines struggle in a modern world dominated by Western science, technology and philosophy. Nazrul says they have fallen short where it matters most: providing proof of efficacy, delivering health care on a mass scale, and competing for resources to find cures for sickness and diseases. Western medicine dominates in the mainstream health service delivery and accounts for a large share of the national health budgets, in India and China.

How did the medical knowledge of the ancients end up being relegated to the status of “alternative treatments” and “supplements”?

“Schools for Western medical education opened in Beijing, and Canton in 1870 and Tientsin in 1881,” Nazrul says. In India, Western medicine took hold under British control through the East India Company before India’s formal handover to the British crown in 1858.

To keep alive their knowledge of ancient healing, China and India have been supporting a hybrid system that trains local doctors in both Western and traditional medicines.

“Students enrolled in indigenous medical schools (had) to learn a number of courses taught in Western medicine,” says Nazrul. The systems wanted to “professionalise” their traditional medicine doctors by allowing them to also practise Western medicine “with some restrictions”.

There are several factors behind traditional medicines’ lack of progress. Without a robust theoretical framework, practitioners will continue to struggle to build a science out of their knowledge, Nazrul says. There are no visible champions or articulate experts to explain traditional medicines to a sceptical world.

Traditional medicines focus on preventing disease and preserving health; Western medicine is still largely focused on curative care. This dooms traditional medicine practitioners to a poorly paid career as the focus on illness-prevention doesn’t lead to demand for expensive equipment, pills or lucrative research grants.

Many modern ailments can be traced to our constant pursuit of instant gratification in today’s high-pressure lifestyles, says Nazrul. People tend to overeat or eat unhealthy foods, exercise too little, abuse substances and lack sleep. As a result, problems develop around the brain, heart, liver, kidney and other organs and require medication, surgery or other expensive forms of treatment. Cures and the costly search for cures are critical to the health of today’s profit-driven health care industry.

The overwhelming might and spread of the Western health care industry is, ironically, stoking hopes for a revival in traditional medicines. Driven by market forces, corporations bent on creating new products and controlling their global supply chains are transforming Chinese herbal medicines and Indian ayurvedic products from small-scale home-based operations to mass commodities for global export – a process Nazrul describes as reverse colonialism. Heavily advertised and packaged to appeal to the senses, traditional medicines have lost their innocence as gifts from nature. While this is helping to boost these products’ visibility and accessibility, he says it underlines Asia’s failure to advance its own cause.

“Many people have become disillusioned by the high cost of Western health care. They also question the intensive use of drugs to ‘cure’ diseases, and various psychiatric and psychological disorders,” says Nazrul.

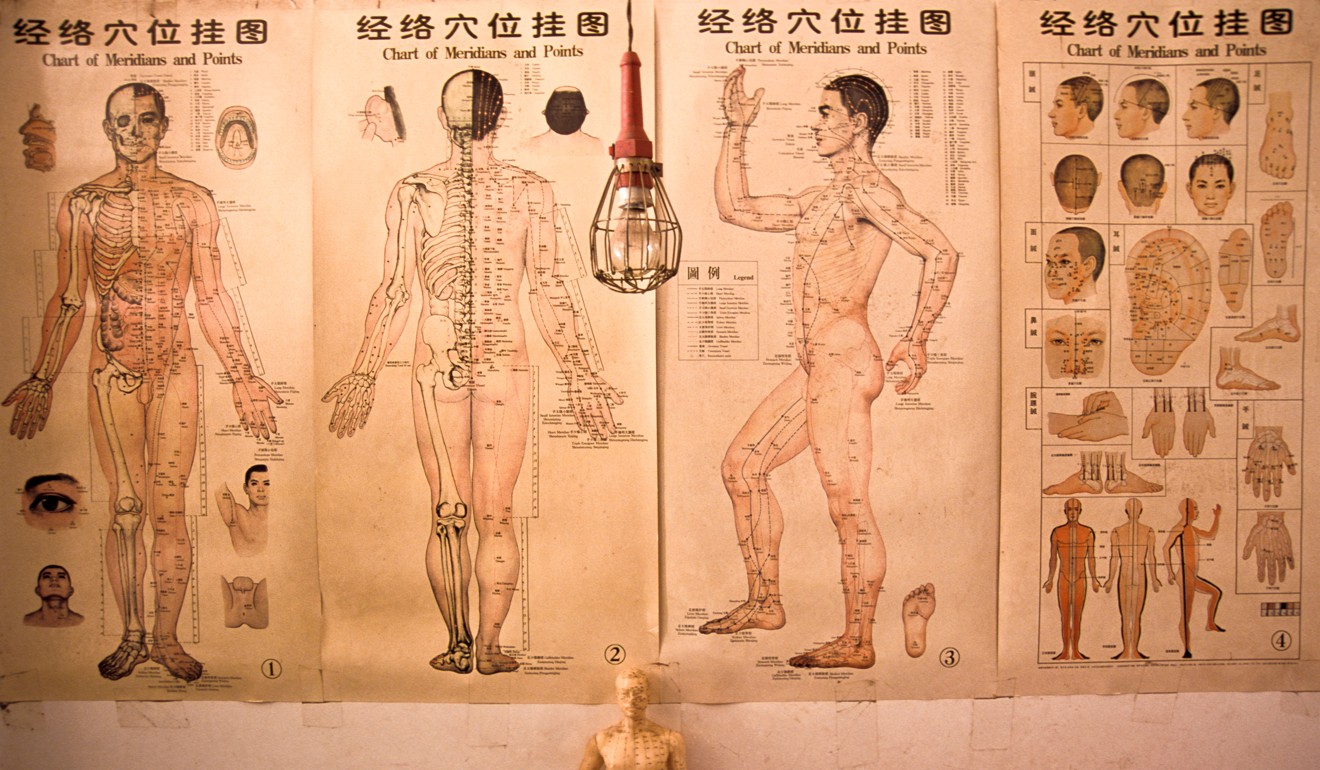

Because they gained acceptance in the West, acupuncture and yoga have become “cool” around the world even though modern science may never fully understand acupuncture’s ‘chi energy’ or yoga’s mindfulness.

In revisiting the issues that concerned the world’s two oldest medical civilisations, Nazrul concludes that they are just as relevant today. The modern world, driven to exhaustion and conflict by the relentless focus on profit and science, will have greater urgency to consider traditional medicines’ wisdoms of balance, harmony and abstinence.