How US scientists diagnosed sane people as schizophrenic, tricked by a secret experiment

An experiment in 1973 sent eight healthy people into hospitals, falsely complaining of hearing voices. The results shook the world of psychiatry and the effects are still being felt in the field today

It was a secret experiment. There was a graduate student, a housewife, a painter, a paediatrician, a psychiatrist and three psychologists. Using fake names, they visited 12 hospitals across the United States and claimed to hear voices. Their mission was to see what would happen. What they found rocked psychiatry.

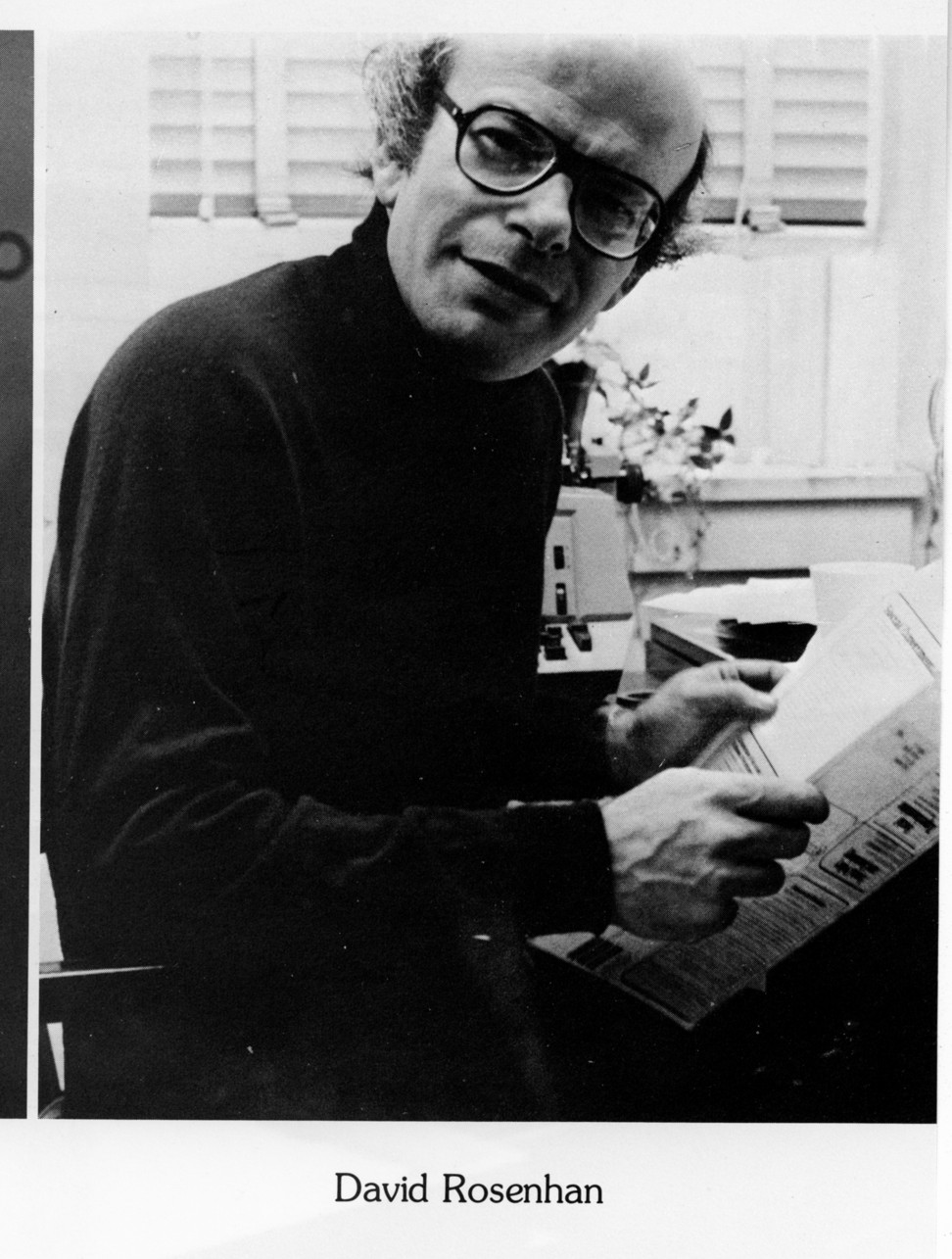

David Rosenhan, a psychologist at Stanford University, published the results of the experiment in a 1973 issue of the journal Science. “On Being Sane in Insane Places” would become one of the most influential studies in the history of psychiatry.

All of them were admitted to psychiatric units, at which point they stopped reporting any psychiatric symptoms. Still, nearly every person in the experiment was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Their hospital stays ranged from seven to 52 days. Doctors prescribed them more than 2,000 pills, including antipsychotics and antidepressants, which the pseudo patients largely discarded.

Hong Kong researchers discover crucial piece to mental illness puzzle

In the hospitals, staff often misinterpreted the pseudo patients’ behaviours to fit within the context of psychiatric treatment. For example, the pseudo patients took copious notes while studying the environment of the psychiatric ward. One nurse reportedly wrote in the chart, “Patient engages in writing behaviour”.

Although none of the pseudo patients were unmasked by hospital staff, other patients on the psychiatric units became suspicious of them. Some 35 patients expressed doubts that the pseudo patients were actually mentally ill, according to the study.

Still, Rosenhan’s conclusions were stark: people feigning mental illness all gained admission to psychiatric units and, after they stopped faking symptoms, remained there for lengthy periods. He famously wrote: “It is clear that we cannot distinguish the sane from the insane in psychiatric hospitals.”

The study has been called a “disaster” and an “albatross” for psychiatry. Its findings generated intense debate over the validity of psychiatric diagnoses and practices, with critics heralding the study as proof of the inherent flaws in psychiatric care.

There is a term for visiting hospital faking illness for a purposeful gain: it’s called malingering. Patients may malinger for different reasons, such as getting pain medications or a place to sleep. And it can be difficult to distinguish these complaints from genuine suffering, whether in psychiatry or any other medical field.

Abusive avatars help schizophrenics confront their demons and defeat them, research finds

In 2000, William Reid, a psychiatrist, published an article about malingering. He wrote that “most of the commonly held axioms about separating real from bogus patients don’t hold up under scrutiny. Liars don’t reliably fidget or blink more, avoid eye contact, or use less detail in their explanations”. Spotting a malingerer often requires extended observation, suspicion that a patient may be feigning illness, and collaboration across multiple providers.

It is clear that we cannot distinguish the sane from the insane in psychiatric hospitals

Mental health care was considerably different at the time of the Rosenhan experiment. The pseudo patients appeared to easily find available psychiatric hospital beds. There is no mention of the costs of care or insurance in the paper. Rosenhan described horrific conditions, with staff members beating patients and shouting profanities as if by routine.

In the decades since the study was published, the shortage of psychiatric beds has become a national crisis in the US, with lengthy waits for inpatient care. Psychiatric treatment is now unaffordable for many, even with insurance. On the brighter side, state legislatures and Congress have passed numerous laws to protect patients receiving inpatient psychiatric care.

The Rosenhan study gave the impression that patients could go to a hospital, claim to hear voices and stroll into any psychiatric unit. But this is far from how mental-health care is practised these days.

Lab tests might include electrolyte panels, blood counts, alcohol level, thyroid levels and urine studies to screen for drugs or infection. The emergency physicians might order a CAT scan of the head or other imaging, depending on the patient’s history.

If the results are unremarkable, the emergency department team may consider a psychiatry consultation if the hospital has psychiatrists on staff.

Study finds no link between cat ownership and schizophrenia, despite alarming headlines

In addition to interviewing and examining the patient, a psychiatrist would review the patient’s chart and any available electronic records from other facilities for background information.

If family or friends are available, psychiatrists try to speak with them. And psychiatric teams try to get in touch with previous care providers or anyone else who might add some insight. These evaluations can take hours.

Today, patients usually do not get admitted to psychiatric units just for saying, “I’m hearing voices”. To be admitted to hospital, patients need to have symptoms of a psychiatric disorder – such as hearing voices, suffering from depression and feeling suicidal – that are so profound as to cause safety concerns or significant impairments in daily living, such as dysfunction at work or home.

If the patient were admitted to a psychiatric unit and then suddenly stopped having symptoms, it would be difficult to justify keeping that person on the unit. Insurance would stop paying for the hospital stay. Every day, physicians have to document why someone needs be treated in a hospital rather than in an outpatient setting.

According to Rosenhan, he challenged them to spot pseudo patients that he would send to their hospital. The staff later claimed with a high degree of confidence to have identified 41 pseudo patients – then Rosenhan revealed that he had not sent any at all.

Patient engages in writing behaviour

But some studies that attempted to replicate Rosenhan’s findings have, in fact, reinforced the notion that psychiatry today is not the same as it once was.

A small 2001 study, for instance, followed seven people with well-documented histories of schizophrenia who were actually in crisis and presented themselves to mental-health intake offices; six of the seven were denied treatment, often because of a lack of resources.

In a 2004 book, psychologist Lauren Slater claimed to have gone to nine emergency departments and complained of hearing voices, as in the Rosenhan experiment. Although she reports having been prescribed various medications, she says she was not admitted to a single facility.

New drug for schizophrenia ‘can save Hong Kong government HK$398 million in medical costs’

Nearly half a century after its publication, the Rosenhan experiment has left a lasting impression on psychiatry.

Researchers continue to propose methods of redoing the study – for example, by asking psychiatrists what they would do with similar patients or by sending actors in randomised trials to hospitals to feign hallucinations.

While such studies may shed light on how mental-health care has changed since the 1970s, it’s already well established that catching impostors is a tall order in virtually any field of medicine.

Using fake patients was a radical way to expose the limitations of psychiatric treatment. But it’s a shame that doing so has sown lingering doubts about mental-health care.

Nathaniel Morris is a resident physician in psychiatry at the Stanford University School of Medicine.

The Washington Post