Immunotherapy, a less toxic cancer treatment than chemotherapy, is making progress ‘slowly but surely’

Immunotherapy, which trains T-cells in the body to detect and kill cancer cells, is a growing field in which the pharmaceutical industry is investing heavily, and many experts consider it a turning point in the fight against cancer

John Ryan is just one of the miracles to emerge from the Johns Hopkins cancer unit in Baltimore in the US state of Maryland.

His life was saved by an immunotherapy treatment – highly effective in a minority of patients – after a lung cancer diagnosis. The retired military nuclear reactor specialist will celebrate his 74th birthday this month.

Chemo not needed in many lung and breast cancers, major studies show

His battle with cancer illustrates the promises and failures of immunotherapy, a burgeoning field in which the pharmaceutical industry is investing heavily.

Ryan has been able to attend the graduations of three of his children, and will take part in the wedding of one of his daughters this summer – even though doctors expected he had just 18 months to live in June 2013.

“That’s exciting stuff to be around for,” he said.

But he knows of plenty people who have not been so lucky. “In five years, I have lost a lot of dear friends.”

Immunotherapy is one of two major categories of drugs against cancer. The best-known is chemotherapy, which has been used for decades with the aim to kill tumours. The drug, though, is so toxic that it also attacks healthy cells, leading to major side effects including weakness, pain, diarrhoea, nausea, and hair and weight loss.

Ryan went through all that in 2013, and his tumour persisted.

They shot me with chemo, it almost killed me. And now I have been sucking up immunotherapy, and it’s been good. My quality of life has been great

Exhausted by chemo and racked with pain, Ryan was accepted into a last-ditch clinical trial using nivolumab (brand name Opdivo) in late 2013.

The drug was delivered intravenously at the hospital, at first every two weeks, then once a month.

His tumour rapidly disappeared, and 104 injections later, the main side effect has just been itching.

Recently, a mysterious mass appeared in his right lung. It was treated with radiation.

“They shot me with chemo, it almost killed me. And now I have been sucking up immunotherapy, and it’s been good. My quality of life has been great,” Ryan said.

Immunotherapy trains T-cells – part of the body’s natural defences – to detect and kill cancer cells, which otherwise can adapt and hide.

Some experts are cautious, having been disappointed numerous times by other newfangled approaches to fighting cancer.

But many consider immunotherapy a turning point. More than 30 immunotherapy drugs are in development, and 800 clinical trials are under way, according to Otis Brawley, chief medical and scientific officer for the American Cancer Society.

Ryan’s oncologist, Julie Brahmer, said she now starts about a third of her lung cancer patients on immunotherapy first, not chemo.

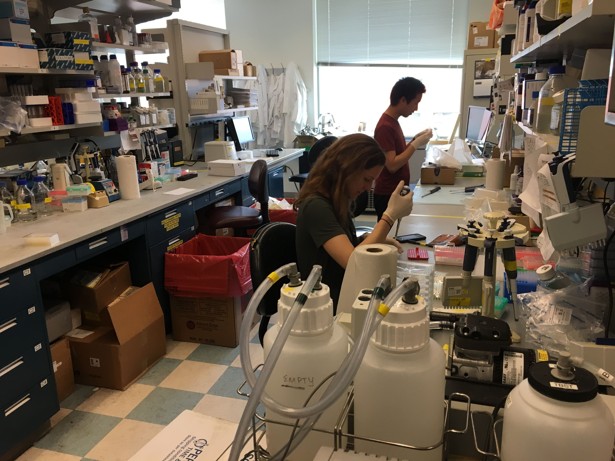

It helps that the Baltimore facility has numerous clinical trials under way, far more than the average US hospital.

Doctors are intrigued by the unusually long remissions seen in a small number of patients like Ryan. These success stories make up about 10 to 15 per cent of patients, said William Nelson, director of the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Centre, the cancer unit at Johns Hopkins. Normal remissions typically last a year and a half to two years.

Chemotherapy and radiation are still the most dominant tools in fighting cancer. But in recent years, a series of clinical trials have shaken up the cancer world, showing it is possible to better treat and even cure some of the most difficult forms of cancer without resorting to the most toxic techniques.

A spectacular example concerns prostate cancer. Researchers have found that recommendations of regular screening had the opposite effect of what was intended, resulting in too many tumours that would never have spread being treated in operations.

Regarding breast cancer, a major study published in early June at the American Society of Clinical Oncology conference showed that for tens of thousands of women, surgery and hormone therapy were enough to keep cancer away. Chemotherapy was being given unnecessarily, they found, in a finding that surprised the cancer community.

Meanwhile, genetic analyses are becoming ever more common for tumours, allowing more precise and rapid treatments for patients.

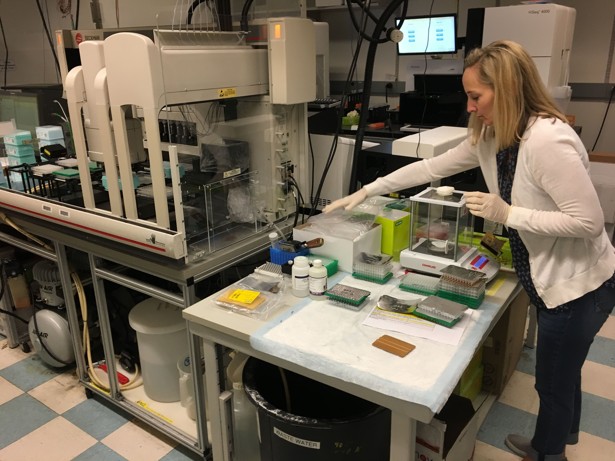

Johns Hopkins has a genomic lab designed to help doctors personalise patient treatments, rather than basing treatment simply on the location of the tumour.

“At this point we have better and better tools to say, ‘Yes, he needs to be treated, you don’t,’” Nelson said.

Some cancers, including brain cancer, remain on the margin of these new treatments.

But for leukaemia, breast, lung, cervical, colon and rectal cancer, as well as the serious skin cancer known as melanoma, immunotherapy and other personalised treatments are making progress “slowly but surely”, Nelson said.

Hong Kong professor takes lead on cancer immunotherapy trial

For oncologist Julie Brahmer’s part, she hopes that one day, metastatic cancers – those that can spread to points distant from the site of origin – will be treated like a “chronic disease”, rather than a death sentence.

John Ryan has a simpler objective in mind.

“My goal is to die of something other than lung cancer,” he said.

.png?itok=arIb17P0)