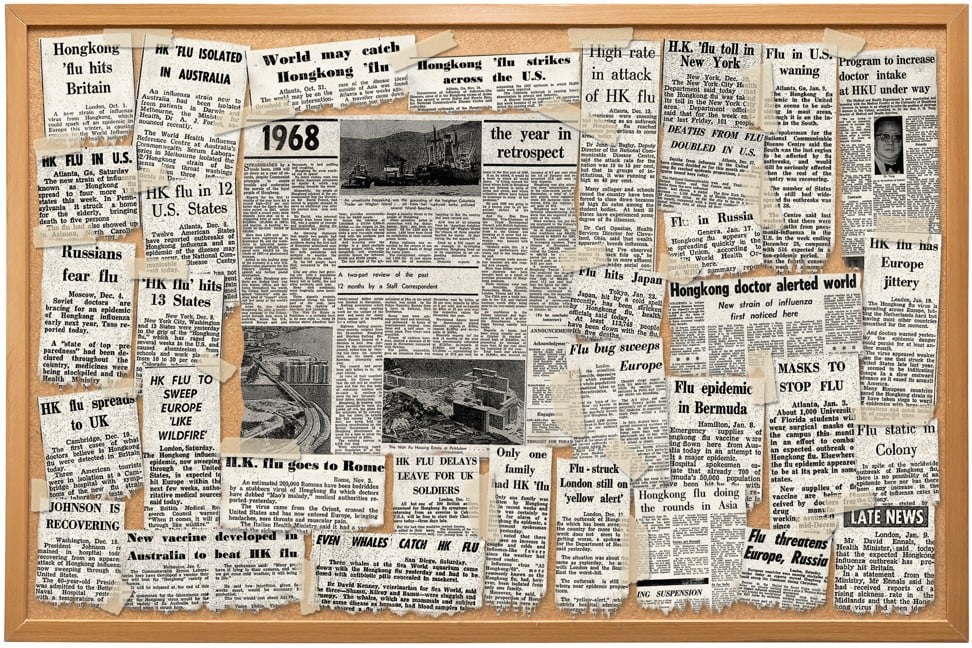

How Hong Kong flu struck without warning 50 years ago, and claimed over a million lives worldwide

Known formally as H3N2, the flu strain was highly contagious, and left clinics in the city packed, with 500,000 people infected, before it steadily spread through Asia, Australia, Africa, South America, Europe and the US

Today, July 13, marks 50 years since the first case of Hong Kong flu was reported in the city. That was in 1968, and over the next six months the disease would claim more than one million lives as it spread to Vietnam, Singapore, India, the Philippines and on to Australia, Africa, South America and Europe.

America wasn’t immune either. The virus entered California via troops returning from the Vietnam war, but didn’t become widespread there until December 1968.

Worldwide, the deaths from Hong Kong flu peaked in December 1968 and January 1969.

Is Hong Kong ready for the next deadly epidemic?

Named Hong Kong flu because it originated in the then British colony, and known formally as H3N2, the strain infected about 500,000 residents of Hong Kong, or 15 per cent of the population.

While the strain had a relatively low mortality rate (the 1918-19 Spanish flu pandemic, for example, killed between 25 million and 50 million) it was highly contagious. Symptoms lasted four to five days, and in some cases up to two weeks. The infection caused upper respiratory symptoms typical of influenza, including chills, fever, muscle pain and weakness.

In a Post article published on July 24, 1968, an unnamed Hong Kong health official said while clinics were packed, there was little that could be done, and the best thing those infected could do was to go home and stay in bed until the condition improved.

“In the meantime, they can take aspirin, tea, lemon drinks, whisky or brandy according to taste,” the official was quoted as saying.

The following day, July 25, the Post reported on the toll the flu was taking on public utilities and industry.

“Worst hit among the public utilities were the Hongkong Telephone Co, and China Light and Power. Two hundred of 300 workers of each company were affected,” the newspaper reported.

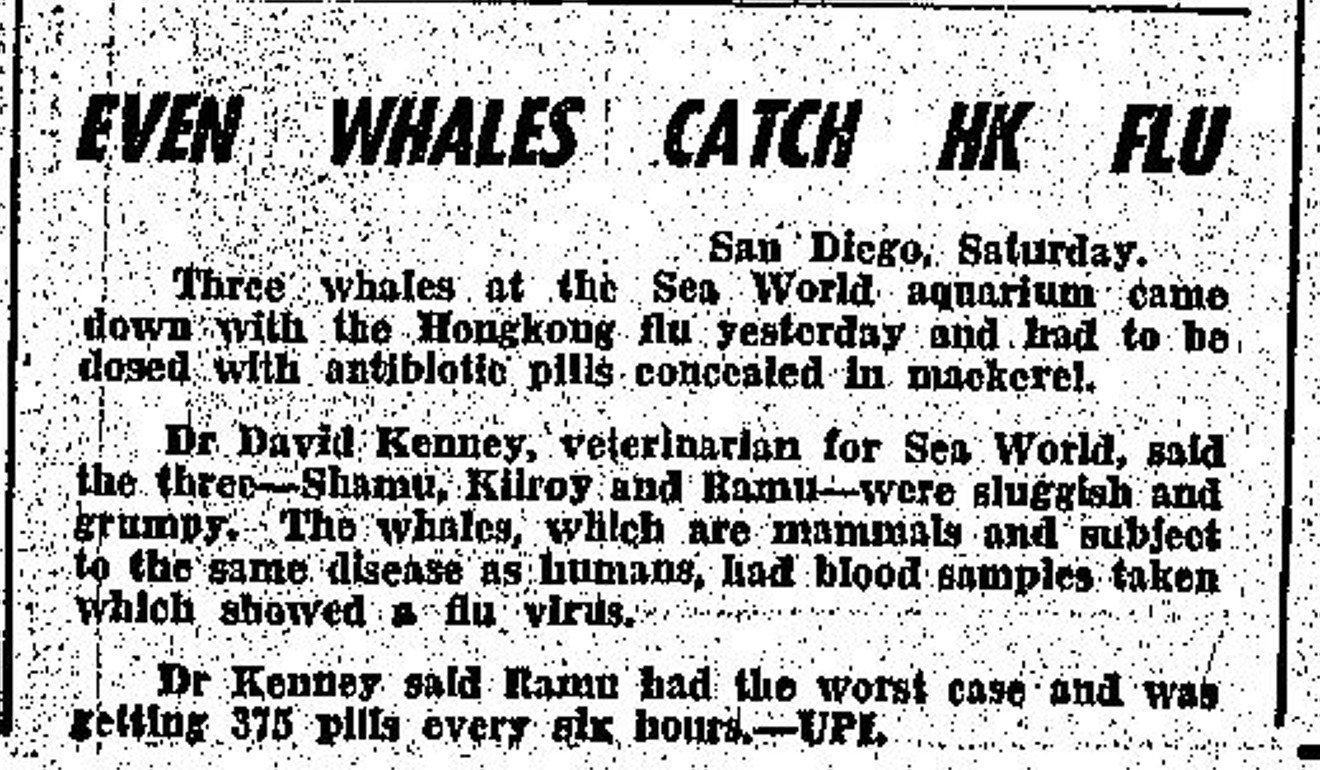

And it wasn’t only human life that was impacted.

On May 1, 1969, the Post published a story by international news agency UPI with the attention-grabbing headline “EVEN WHALES CATCH HK FLU”. The report said three whales – Shamu, Kilroy and Ramu – at Sea World in the Californian city of San Diego had come down with Hong Kong flu and had to be dosed with antibiotic pills concealed in mackerel. (Ramu was the hardest hit, and was getting 375 pills every six hours, according to his veterinary surgeon, Dr David Kenney.)

A January, 1970, report in The New York Times said “scientists suspect that at least three of the recent pandemics of influenza began in mainland China”. An excerpt from the story reads: Dr Chang Wai-kwan of Hong Kong’s Queen Mary Hospital, was quoted as telling an international conference: “The Asian flu of 1957 apparently originated in the central mainland of the People’s Republic of China and the epidemic of 1968 possibly could have come from the same source.”

China, rather than Spain, was also now believed to have been the source of the deadliest 20th century flu epidemic, the report said.

“The great pandemic of 1918-1919, erroneously called the Spanish flu, appeared first in villages in China,” a recent review in the British Medical Journal said. “The epidemic of 1889, which moved from the depths of Russia westward across Europe, could also have originated in China, Dr Alexander D. Langmuir, chief epidemiologist at the [US] National Communicable Disease Centre in Atlanta, said.”

How hectic Hong Kong is turning into hotbed of infectious diseases

“So far as the isolation and characterisation of the virus were concerned, the programme fulfilled its objective and, thanks to the efforts of the national reference centre in Hong Kong and the two international centres, the strain was isolated, identified and distributed to vaccine producers with all possible speed,” the report said.

“It is difficult to imagine circumstances in which the interval from arrival of specimens in a national influenza centre to the characterisation and distribution of the strain could be shortened.”

The virus is still in circulation today, surfacing from year to year in mutated forms of seasonal influenza, rendering vaccines less effective.

And while advances in medicine and technology means fewer deaths, seasonal flus can still be fatal. Just last week a nine-year old girl died in Hong Kong after catching the flu, the third such death reported in 2018. (She had other chronic illnesses.)

Hong Kong flu is was not the only deadly disease outbreak to have hit the city. In 1997, 18 people were infected and six died when H5N1 bird flu first jumped the species barrier from poultry to people. In late December that year, the government ordered the slaughter of 1.3 million chickens in a bid to stop the spread of the disease.

Young Hong Kong girl dies after catching flu infection, the third such death this year

In 2009, Hong Kong recorded the first case of swine flu in Asia. But nothing hit the city harder than Severe acute respiratory syndrome (Sars) in 2003, which infected 1,755 people in Hong Kong and killed 299 of them.