Hi-tech iTBra a breakthrough for Asian women at high risk of breast cancer

- Women with so-called dense breasts – prevalent in Asia – are six times more likely to develop breast cancer than other women

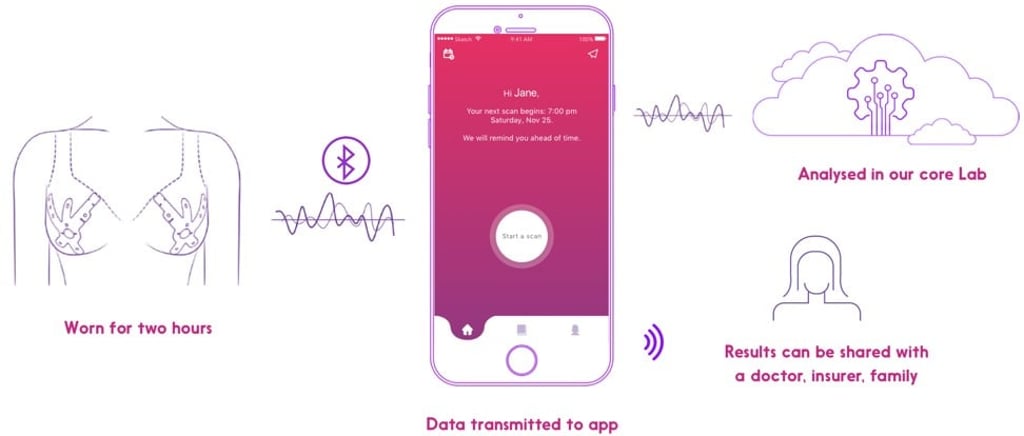

- Hi-tech bra inserts detect circadian temperature changes and previously undetectable small tumours

Women may eat healthily, exercise daily, sleep regularly and have no family history of breast cancer, yet still face a high risk of developing this disease – if they have so-called dense breasts. A new hi-tech bra insert may alert at-risk women to changes in their breasts, giving them an early warning to see a doctor.

Research has shown that dense breasted women can be six times more likely to develop breast cancer. Sixty per cent of younger women and 40 per cent of older women who have gone through menopause have dense breasts.

Breast density among Asian women is higher than in Western women, says Dr Michael Tiong-Hong Co, a clinical assistant professor in the University of Hong Kong’s surgery department.

Dense breasts have more dense tissue than fatty tissue. That dense tissue can hide some tumours, making them difficult to detect through imaging.

Undetected, cancer can accelerate, says Rob Royea, CEO of Cyrcadia Asia, maker of the iTBra, a new device to help detect cancer in women with dense breasts. Unfortunately, most cancers and tumours are not found until the disease is at an advanced stage.