Vaccinations in India: the heroes helping children from poor families get immunised, and how they do it

- Poor Hindus and Muslims throughout India harbour dangerous misconceptions about vaccinations, meaning millions of children miss out

- The situation is improving thanks to community figures who break down barriers, and a government that is learning valuable lessons

“Come any closer and I’ll drop him,” shrieked the man, holding his baby upside down by the legs above a well.

Word had reached the village outside Varanasi, a city in northeast India, that a government team was coming to vaccinate babies and young children. The father had grabbed his son and rushed to the well in the fields. His threat was shouted at Ibrahim Khan, part of the team, as he approached the distraught father.

That day, Khan was forced to beat a tactical retreat. It took many visits to persuade the Muslim families in the village that the vaccines would not make the baby boys impotent.

“Eventually that man too came round and we vaccinated his son. In some places, people threw bricks and stones at me, once boiling water from the first floor. But it’s that baby hanging over the well I can’t forget,” Khan says.

Zombie theories: History of vaccines and understanding immunisation

Khan was accompanying the team of health workers, but he is not with the government. His real job is running a pathology laboratory. His voluntary work, as a trusted person in the Muslim community in Varanasi, is helping to persuade Muslim families to vaccinate their children as part of the government’s efforts, backed by Unicef, to protect every child from vaccine-preventable diseases through immunisation.

Varanasi is a holy city for Hindus. Muslims are a minority both in the city and throughout India. The majority are very poor and uneducated. Poor Hindus also harbour misconceptions about vaccinations but what complicates matters among poor Muslims is that, as a minority that often feels insecure, a “besieged” mentality can render them more vulnerable to rumours.

“Some think that vaccines are a way of targeting Muslims, making them impotent as a way of reducing the Muslim population,” Khan says.

Having earned their trust first, the ebullient Khan tells families that it is their duty under Islam to protect their children from fatal childhood diseases and that Muslim countries also vaccinate children and pregnant mothers.

“I tell them that if they want to go for ‘haj’ [pilgrimage to Mecca], the Saudi government won’t let them enter the country unless they have had the polio, meningitis and hepatitis B vaccine. All this breaks down their mistrust,” he says.

Community figures like Khan are playing an important role in immunising poor and vulnerable groups against sickness and life-threatening childhood diseases such as polio, rotavirus, hepatitis B, measles and rubella.

India has made considerable headway in immunisation over the past few decades, but a lot remains to be done on routine childhood vaccination. The country has the largest number of births in the world – more than 26 million a year – and also accounts for more than 20 per cent of child mortality worldwide. Every year, the government organises nine million immunisation sessions to target these infants and the 30 million women who fall pregnant annually.

To convince them about polio, I take the drops [of the vaccine] myself in front of them

Yet an estimated 38 per cent of children in India aged 12-23 months failed to receive all basic vaccines in 2015 and 2016, according to the country’s National Family Health Survey. That means the national average for full immunisation is 62 per cent, but vaccination coverage varies considerably from state to state, with some states and rural areas having very low coverage.

The polio story in the country has been a success. India has been polio-free for the past eight years. And lately the government has introduced new vaccines, such as IPV, PCV and the combined measles-rubella vaccine (MR) that have become part of the universal immunisation programme for the first time. Of the 134,200 measles deaths globally in 2015, around 49,200 occurred in India, about 37 per cent. Those who survive are more vulnerable to other serious illnesses such as diarrhoea and pneumonia.

Why don’t mothers have their children vaccinated? Apart from the fears mentioned earlier, the low demand stems from the fact that they often have no idea what a vaccine is, what it does, or where and when it is going to be made available. Some fear the child will get a fever or fall sick. They are scared of side effects. Migrant labourers miss vaccination sessions. Some communities are in remote areas that are hard to reach.

Owing to this low coverage, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare launched Mission Indradhanush in 2014 to target those children who were missing out. By 2017, around 25.5 million children and 6.9 million pregnant women had been vaccinated. To give one final push, in October 2017 it launched the Intensified Mission Indradhanush (IMI), an ambitious plan to push for 90 per cent immunisation for children aged 12-23 months in areas with persistently low levels.

According to surveys conducted by the World Health Organisation and the United Nations Development Programme, there has been a 18.5 per cent increase in full immunisation coverage in the areas where the latest push happened.

Valuable lessons have been learned in what works: mobilise community leaders like Khan; motivate and train midwives and health workers who work with pregnant women and young children; catch migrant labourers at bus stops and railway stations; ensure that no vaccination camp is more than a 15-minute walk from their homes to make it more likely families will come; hold the sessions early in the morning so that fathers don’t miss a day’s work; and go door-to-door to raise awareness.

Nasal spray vaccine touted to help fight flu among Hong Kong pupils

The campaign has involved enlisting the help of Muslim religious leaders to preach the right message in mosques. But the principals of madrassas (Islamic schools) have to be convinced. Last year, hundreds of madrassas across western Uttar Pradesh refused permission to health officials to administer the MR vaccine to students. The fear was based on “sterilisation” rumours spread on WhatsApp.

What works is usually a combination of information, reassurance, compelling gestures – “To convince them about polio, I take the drops [of the vaccine] myself in front of them,” Khan says – and key messages.

“We stress that if they don’t give their child the vaccine and the child falls ill, the parents will lose wages and have to spend on medical expenses,” says Dr Mahesh Pande, who heads the primary health care centre in the Badi Bazar area of Varanasi.

On a mild winter morning, the clinic is full of burka-clad Muslim women and children. Unicef regional coordinator Sajid Ali has come to meet Pande, a government employee. The government and Unicef have been working closely to train health workers on how to reach and persuade reluctant families to come for the vaccines.

Language, they have realised, is important. They take care to avoid saying the vaccines are “new”, for example, because the word makes some people nervous. Nor do they say that a child after a vaccine “will” get a fever. They are trained to say “may” because “will” puts some people off.

“To quell suspicions, we point out that private doctors in India have been giving the vaccines for 40 years, it’s just that the government is making them available, free, to them, for the first time,” Ali says.

If it helps, Islam is invoked. The Koran enjoins Muslims to pray five times a day. How will they do that if they are unwell?

“We also point out, in case they have doubts about the government’s intentions, that Unicef is not a local NGO but an international organisation,” Ali says.

Hong Kong’s first nasal spray flu vaccine should be trialled in mainland China

By noon, around 17 children have been vaccinated. The mothers all live in joint families where elder relatives pooh-pooh vaccination. The younger mothers have to fight against their reluctance.

“My parents and in-laws all told me they had never been vaccinated and they have been fine so why do I bother?” says Shabana Parveen, whose daughters got an MR shot from the nurse. “But my local health worker told me I must bring my daughters here.”

It is not only poor Indian Muslims who must be won over. The latest WHO figures this month show that efforts to halt the global spread of measles are, in the WHO’s words, “backsliding”. Case numbers worldwide are soaring, putting years of progress made in reducing the killer disease at risk. This includes wealthy nations where vaccination coverage has historically been high.

I said Islam says that if you are sick, get treatment. If you are not sick, take all precautions not to fall ill. This made sense to them. I think the mood is changing. People are beginning to understand

In India, though, there is no turning back. The government will integrate lessons learned into its universal immunisation programme. You can see the success at a nearby Outreach Site in Varanasi’s Kamalgarha area, not far from the Bada Bazar clinic. Nusrat Bareen and her husband have come for a tetanus booster shot for their two-year-old son. On her desk, nurse Sangeeta Dube has a range of vaccines laid out. As she gives the shot, she explains to Bareen that her son “may” get fever.

Zannat (known only by one name) has come with her angelic baby girl. She wasn’t planning to. In the morning, her husband told her not to come for the vaccination because their little girl had already been sick. When Zannat didn’t show, community worker Sabha Iqbal went to her house, after her husband had gone to work.

“She told me that if I didn’t have this third vaccine, the earlier two would not work, so I came,” says Zannat, cradling her baby girl.

Even so, Zannat has some doubts. “We all fall sick at some time, so what good is the vaccine?” she asks. Iqbal quickly replies: “True, we can all fall sick at any time, but these vaccines are for life-threatening diseases.”

Experts denounce Canto-pop star’s claim of harmful flu jabs as ‘totally wrong’

The dedication of workers like Iqbal is striking. They won’t take no for an answer. Iqbal has knocked at doors and been told by the person who opened it that “there is no baby here” or “the baby has gone to his grandparents” when she knows full well that there is a baby inside that needs to be vaccinated. Isn’t it difficult to keep hammering away at reluctant families?

“No, I like it when they finally turn up with their children and I know I am going to be able to protect the babies’ health,” Iqbal says.

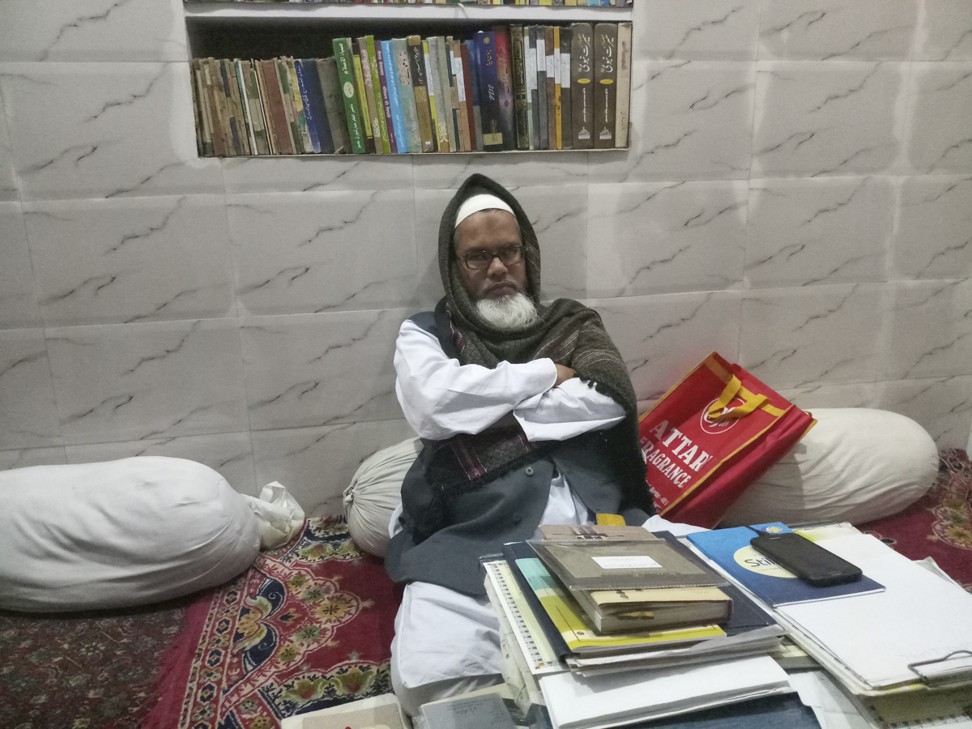

The local mosque is at the end of a maze of alleys, empty save for the clacketing sound of power looms. Muslim weavers have their tiny workshops here where they make the famous Varanasi brocade silk sari. Inside the mosque, in a cold basement room, the mosque head, Maulana Abdul Batin Nomani, sits on the carpet with his books.

Since he was only 25 when he took on the post of Maulana – religious scholar – he was able, as the father of two young children, to set an example. He had both children vaccinated and told the congregation why.

“I said Islam says that if you are sick, get treatment. If you are not sick, take all precautions not to fall ill. This made sense to them. I think the mood is changing. People are beginning to understand,” he says.

Khan, now in his early 60s, agrees. Most men his age are retired and playing with their grandchildren but Khan is still a dynamo, mobilising the community.

“The next generation must be healthy if India is to prosper,” he says. “Good health is the right of every child.”