Factory farming seen to trigger next global pandemic: choose plant-based meat alternatives to reduce the threat

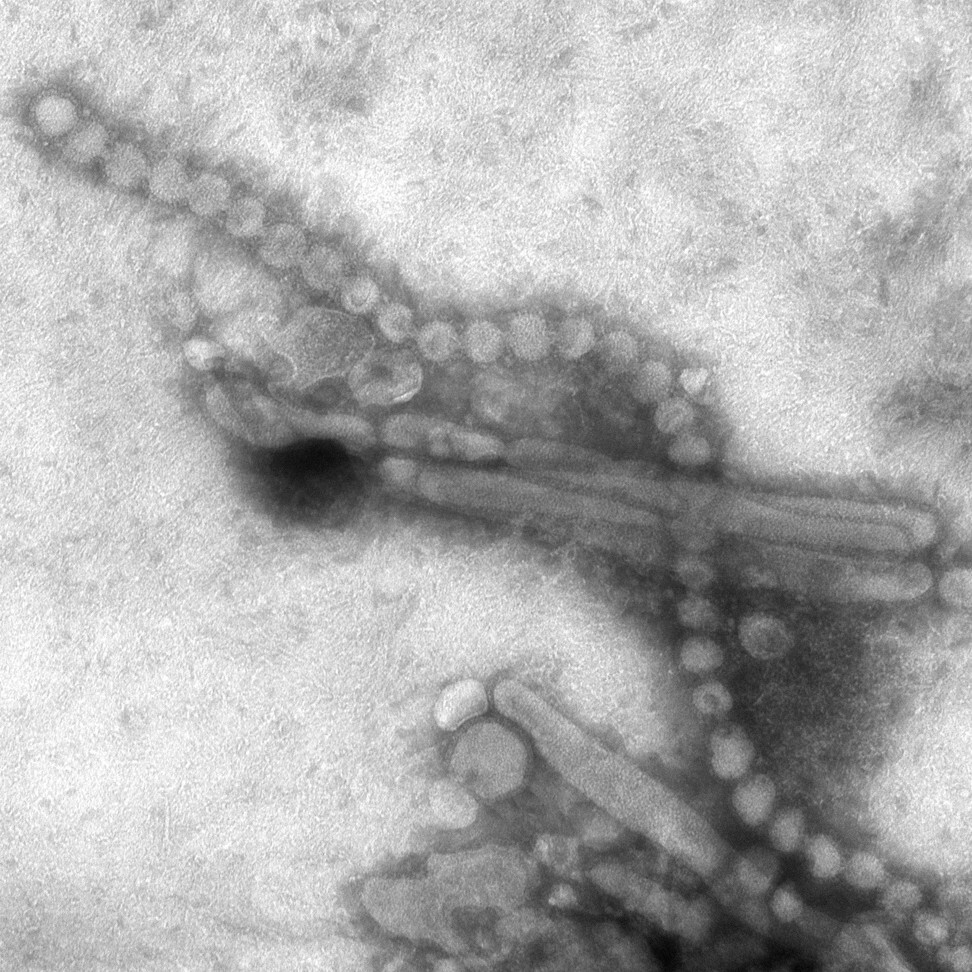

- Experts say the next pandemic will be a bird flu, H7N9, which so far has killed 40 per cent of people infected, making it 100 times deadlier than Covid-19 virus

- It will start in battery chicken farms, so consuming less cheap, factory-farmed meat and eggs and eating more plant-based alternatives can help head it off

At the online PlantFit Summit this month, 38 of the world’s health experts weighed in on how to improve our health and well-being by adopting a more plant-based diet.

Opening the summit was US doctor Dr Michael Greger, The New York Times bestselling author of How Not to Die and internationally recognised speaker on nutrition, food safety, and public health. He spoke about the next killer flu, which he believes is brewing in battery chicken farms.

The first reported incidence of H7N9 was in China in March 2013. Since then, sporadic annual human infections have been reported, with China currently experiencing its sixth epidemic. During the virus’ previous and fifth epidemic, from 2016 – 2017, the World Health Organization reported 766 human infections, making it the largest H7N9 epidemic to date.

The H7N9 virus is of special concern because most patients who contract the virus experience severe respiratory illness, such as pneumonia.

According to the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Asian lineage H7N9 virus is rated by the Influenza Risk Assessment Tool as having the “greatest potential to cause a pandemic”, as well as posing the highest risk of severely impacting public health if it were to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission.

Industrial farming of livestock a ticking pathogen bomb, scientists say

According to the CDC, the eight genes of the H7N9 virus are closely related to bird flu viruses found in domestic ducks, wild birds and domestic poultry in Asia.

The virus likely emerged from “reassortment”, or mutation, a process where two or more influenza viruses co-infect a single host and exchange genes, producing a new strain of the virus.

Experts believe the H7N9 virus underwent multiple mutations in live-bird and poultry markets, where different species of birds are bought and sold for food. Infected birds shed bird flu virus in their saliva, mucus and faeces. Human infections with bird flu viruses can happen when enough virus gets into a person’s eyes, nose or mouth, or is inhaled.

“That’s what viruses do best – they mutate and may find the lungs and become an airborne pathogen,” explains Greger.

Greger says: “We have the same trench warfare conditions today in every industrial egg operation and industrial chicken shed where the animals are confined, crowded, stressed – but by the billions, not just millions.”

It matters how we raise animals around the world, regardless of what we choose to eat, because we are all put at risk by animal farming. “When we overcrowd thousands of animals into cramped football-field-sized sheds, beak to beak or snout to snout, atop their own waste, it’s a breeding ground for disease,” Greger says.

The overcrowding of animals in such conditions leads to stress, which cripples their immune systems. This is made worse by ammonia from their decomposing waste burning their lungs, as well as a lack of fresh air and sunlight. “Put all these factors together and you have a perfect storm environment for the emergence and spread of super strains of influenza,” he adds.

Just as eliminating the exotic-animal trade and live-animal markets may go a long way towards preventing the next coronavirus pandemic, reforming the way we raise animals for food may help forestall the next killer flu.

Companies are developing plant-based foods in response to demand for alternatives to meat as a source of protein. They are primed to expand production as more consumers turn away from cheap, factory meat products.

Such a change is happening in the dairy industry, where cow’s milk sales have fallen as consumers become aware of, and are given a choice of, non-dairy milk alternatives. Dairy produce sales fell by 22 per cent between 2006 and 2016, according to Cargill, the world’s biggest producer of animal feed. In the same period, sales of plant-based milk alternatives tripled.

“All the major meat producers – Tyson, Smithfield, Hormel, Purdue, JBS – have started innovating us out of this precarious situation by making plant-based meat alternatives,” says Greger.

Cargill, the largest private corporation in the United States, is now producing plant-based lines of sausages and chicken nuggets. The world’s largest fried chicken chain, Kentucky Fried Chicken, has started rolling out “Beyond Fried Chicken” plant-based alternatives at dozens of stores in the US in the hopes of going national.

If more people choose these products, corporations will make more of them and the world would be at less threat.

Although doctors recommend eating whole plant foods rather than processed plant foods, Greger says that if you’re at a fast-food chain and you’re going to order something, opting for these plant-based alternatives is not only healthier than the meat option, but from a pandemic disease standpoint “poses zero risk”.

Ocean Robbins is co-author of Voices of the Food Revolution – You Can Heal Your Body and Your World – With Food.

He serves as an adjunct professor for Chapman University in Orange, California, and is the CEO of the online Food Revolution Network, which advocates for affordable and accessible healthy food for all.

Livestock gain weight faster, which increases profits, when they’re fed antibiotics with every feed, and because of this, factory farms have become breeding grounds for antibiotic-resistant bacteria, Robbins says. He adds: “We are creating inevitable future pandemics every day when we take 80 per cent of our antibiotics and feed them to livestock.”

Echoing Greger, Robbins explains that a big way to make a difference as an individual is to eat lower on the food chain, opting instead for whole plant food options.

“You’re not going to be supporting antibiotic use in factory farms if you don’t eat the products of factory farms,” he says.