How to survive world’s longest coronavirus hotel quarantine: 3 Hongkongers tell how they endured 21 long days in isolation

- Business executive Arnaud de Surville woke up crying in his last week of quarantine, while Brenda Adrian mourned the death of her mother during her confinement

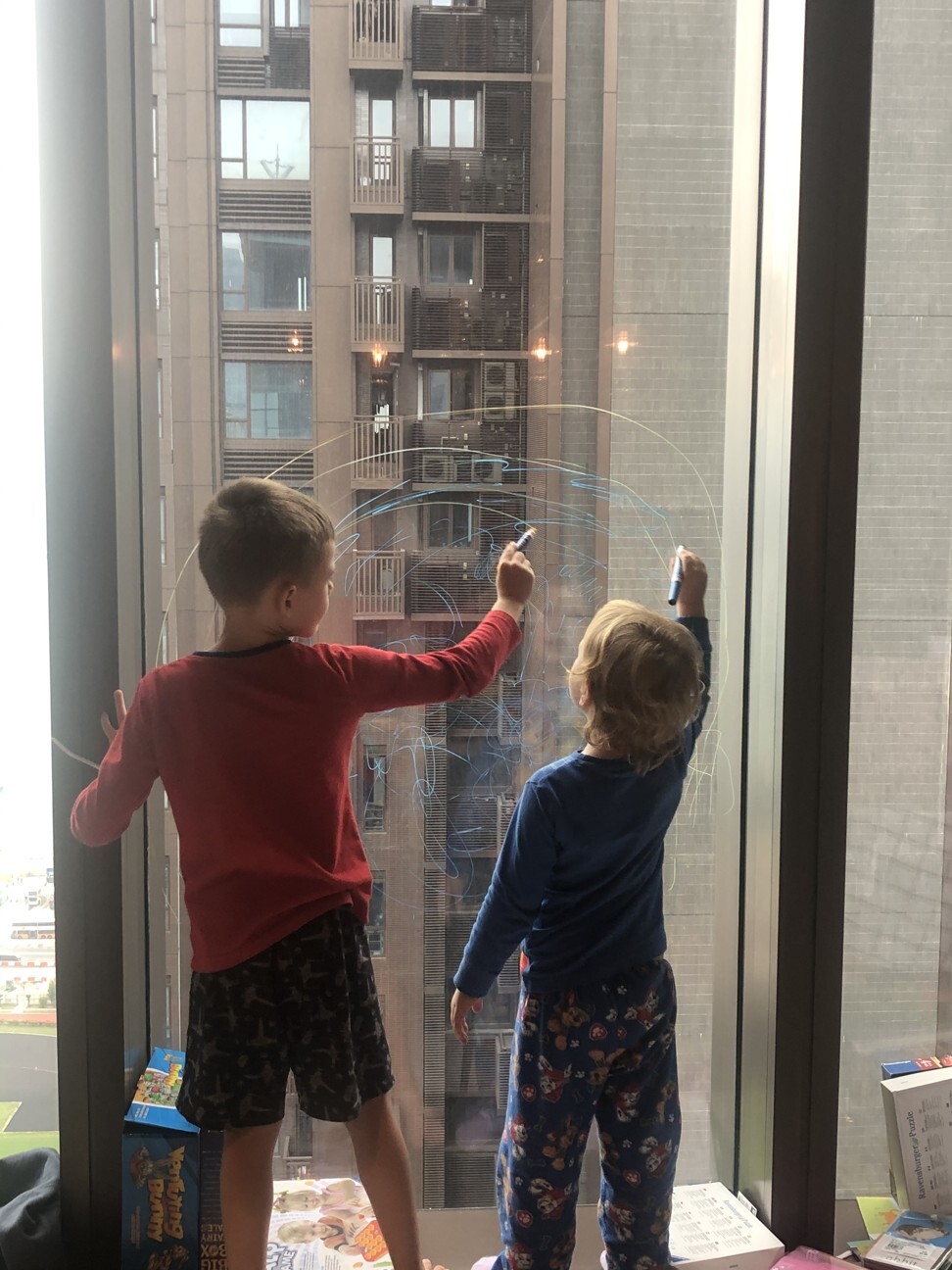

- Zoe Fortune and her husband struggled to keep their energy and positivity going as they quarantined with their two children, aged four and six

In the last week of his three-week hotel quarantine, Arnaud de Surville woke up crying. A successful business executive, he’d never had a mental health issue and hadn’t expected the 21-day isolation to be so gruelling.

“The last week was horrible, I woke up twice in the morning in tears,” says de Surville.

He is not alone. Quarantine has been associated with increased rates of suicide, anger, acute stress disorder, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder, with symptoms continuing even years after the quarantine ends.

When Hong Kong increased its mandatory quarantine period to three weeks in December, it picked up the title for the world’s longest hotel quarantine. The painful cost of 21 days in a hotel and the excruciating red tape have been widely discussed, less so the toll on our mental health.

No matter how well prepared you are, those in quarantine widely speak of the challenges of entering the third week of solitary confinement in a small room, often without access to fresh air.

“My expectation was that when I entered the final stretch I’d be fuelled by new energy, which didn’t happen. Maybe that’s why I was broken,” says de Surville, who was returning from a business trip.

Why Hong Kong’s 21-day hotel quarantine is a band-aid for the Covid-19 crisis

A few days into quarantine, he was spending so much time looking at the ships at sea that he ordered binoculars.

“It became so important. I was reading the names of the ships, recognising them. When you have zero contact, it makes a difference when you see again a ship that you saw a few days before,” says de Surville.

And still it was tough. “It takes determination and willpower to stick to your routine and not let yourself drift,” he says. “After two weeks I’d had enough. I was exhausted.”

It didn’t help that, 10 days into his confinement, the first in-person conversation de Surville had was with the men in hazmat suits who came to give him a Covid-19 test. Their opening line was: “Sit in that chair, give us your passport.” He says he’d had have been grateful for a kind word – “Hello, how are you doing?” would have gone down a treat.

Though de Surville was released on a Friday, he turned down invitations for that weekend to allow him time to resume a normal life.

Mourning in solitary confinement

Long-time Hong Kong resident Brenda Adrian’s mother died in Germany in April and she hurried there to help her father organise the funeral. She returned to Hong Kong on May 7, and began three weeks’ quarantine.

On May 12, she heard that the quarantine period for those from Germany was being cut to two weeks, but her calls to the Department of Health went unanswered, and the German consulate dashed her hopes, telling her she would still need to do the full three weeks.

“Once I arrived here, I fell into a deep hole, I hadn’t even had time to mourn. You are coming back, but can’t even go to your family. It is more than brutal. I wasn’t sleeping. I’ve been on sleeping tablets for six weeks, I’m trying to wean myself off,” said Adrian, speaking from the Dorsett Wanchai hotel in Wan Chai.

Adrian loves her job working at a skin cancer screening centre, but it’s not the sort of work she can do remotely. Without a focus, she says the time dragged.

“You try to make a routine, do exercise, but to get yourself motivated to do anything is a bummer,” says Adrian.

“I felt like crying, but sat there numb, literally numb; it’s like waking out of anaesthesia. I cried a lot. It’s the whole situation, you ask yourself, ‘Where are you these days? What’s the meaning of life?’ I’ve never been like that.”

A 60-something yogi’s three-week quarantine workout for mind, spirit and body

Her daughter and partner sometimes stood outside her window to wave up at her, and occasional treats, such as a pot of flowers from the hotel, helped lighten the days. But the solitary confinement, when she really needed to be with her loved ones, was tough.

“Even prisoners are allowed out for half an hour a day. After three or four days with no sunlight, my skin had turned grey,” she says. An LED light-therapy mask allowed her to relish some healing rays.

“The night before, you get the SMS [that] you can go out, it’s very formal. I found it very stressful,” Adrian says.

Lowering anxiety for children

Quarantining with young children provides its own set of challenges. Zoe Fortune, CEO of the City Mental Health Alliance, has extensive experience in the field of mental health and holds a PhD in Health Services Research from the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience at King’s College in London.

After a family emergency took her back to her native Britain in November, she and her husband faced the challenge of returning to Hong Kong with their two children, aged four and six.

My son started to have nightmares about leaving the room and being arrested by the police. There was anxiety around us, and us being there. It has left a mark on them

Fortune’s advice for quarantining with children begins with having an honest conversation with them about what is going to happen, removing the fear factor. She gave each child a corner of the room and got a little pop-up tent for them.

“If they each have their own space that they have to keep tidy, their own corner of the world, it gives them a sense of control,” says Fortune.

The first two weeks were manageable, but the third week was difficult. “By day 16 it was really hard, I just didn’t have the energy to keep going. As the mum, as soon as my energy went, everyone’s did,” says Fortune.

She also struggled with the lack of fresh air. “After three weeks with four of you in a confined space, the air became quite stale. We got an air purifier, but still the air was stagnant and claustrophobic.”

The most difficult times were the weekends – when the structure of work and home-schooling fell away – and when the people in the hazmat suits came to do their tests, which the children found distressing. Fortune and her husband did their best to make it all a game and joke about the “spacemen” coming.

Covid-19 ‘takes deep toll’ on Hongkongers’ mental health: ex-justice minister

“My son started to have nightmares about leaving the room and being arrested by the police,” she says.

A few months after their ordeal, Fortune says her children are adjusted, but have made it clear they don’t want to go back into quarantine. “There was anxiety around us, and us being there,” Fortune says. “It has left a mark on them.”

If you are having suicidal thoughts, or you know someone who is, help is available. For Hong Kong, dial +852 2896 0000 for The Samaritans or +852 2382 0000 for Suicide Prevention Services. In the US, call The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline on +1 800 273 8255.