What cures dementia? Nothing, but you can delay or prevent its onset with exercise, an active social life and by not smoking

- Anthea Rowan asks whether understanding her mother’s depression can help protect her against developing dementia

- A strong link is seen between depression and dementia; socialising, brisk walks, watching your weight, drinking less alcohol and not smoking may lower the risk

For as long as I can remember, Google has helpfully delivered daily news alerts on “depression” to my inbox. They landed cheerfully – with a little ping – ironic, given they either directed me to economic collapse or mental illness.

I was interested in the melancholic variety, perpetually on the lookout for treatments that might make my mother better.

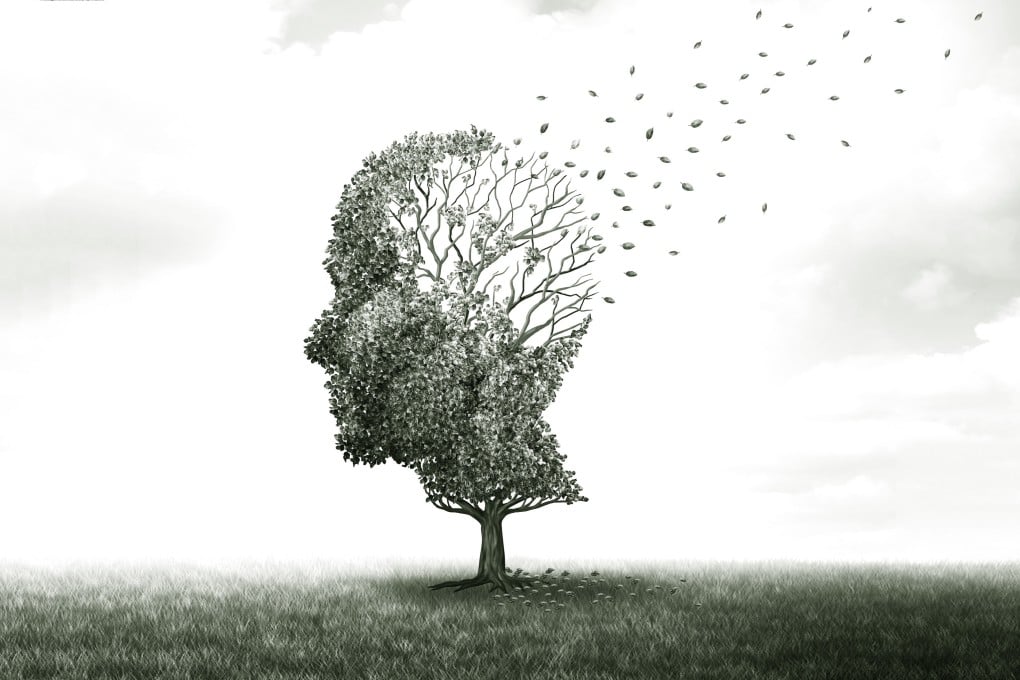

Not long ago, I amended the news alert from “depression” to “dementia”. There is nothing ambiguous about “dementia” – it never takes me down Wall Street – but nor is there anything as hopeful as there sometimes was for “depression”.

There is no cure, no treatment for dementia.

According to the World Health Organization, dementia affects around 50 million people. There are 10 million new cases every year. In Hong Kong, more than 10 per cent of the over-70s suffer from it.

Calvin Cheng Pak-wing, a clinical assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Hong Kong, says there is a strong link between depression and dementia – and that many studies suggest depression is a significant risk factor for developing dementia.