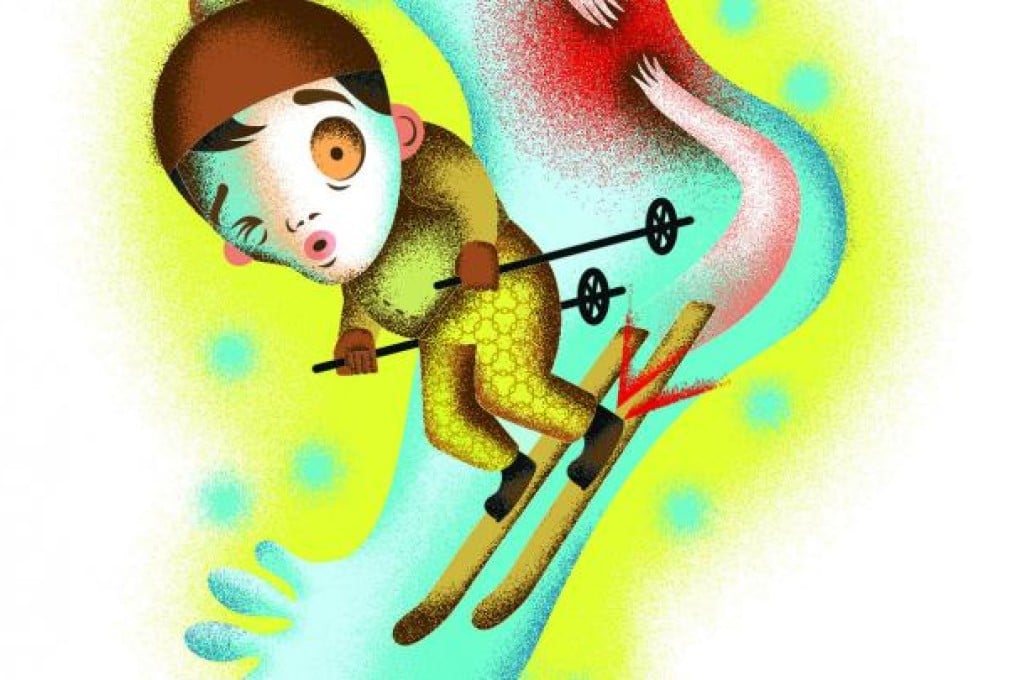

Larry Chung was on his annual skiing holiday in Vancouver, carving his way down powdered slopes when he heard a "pop" followed by the feeling that his left heel was on fire. The 45-year-old banker knew that his Achilles' tendon had ruptured - again.

Ten years earlier, Chung (whose name has been changed for patient confidentiality reasons) had suffered the same injury to his right foot while playing soccer. So he was familiar with the symptoms and sensations of the injury, and also acquainted with the long, drawn-out - and somewhat hazardous - road to recovery. He mentally braced himself for the process as he gingerly made his way to the ski resort's medical centre.

The Achilles' tendon is a band of connective tissue holding the calf muscles to the heel bone. It enables a person to push up on their toes and to push off when walking, running or jumping.

According to Dr Tang Wai-man, a specialist in orthopaedics and traumatology at the Hong Kong Sanatorium and Hospital, the Achilles tendon is the most troublesome part of the human anatomy. The tendon earns its name from an ancient Greek myth about the warrior Achilles, whose mother dipped him into the Styx river to try to make him invincible. However, because she held his heel while immersing him in the magical waters, a small vulnerable spot was created. Achilles was later killed by a shot in the heel from a poisoned arrow.

Doctors know that the Achilles' tendon is vulnerable, not only because it has to bear up to 12 times a person's weight when they are running or jumping, but also - and more importantly - because blood flow to the heel area is poor. Sub-optimal blood flow to any area impedes healing and creates problems.

The last time Chung had to recover from an Achilles' tendon rupture, he spent three months hobbling around with his foot in a cast and developed deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Hence, he knew he needed his loved ones near during recovery to make the uncomfortable road ahead more bearable.