New | How London's Battersea power station will become luxury living hub

Iconic building to be transformed into mixed-use 'village' of homes, retail and office space, and more. Wilkinson Eyre is behind its dramatic renovation. The wider site includes housing schemes by architects Frank Gehry and Norman Foster

It shot to international fame after appearing on Pink Floyd's Animals album cover in 1977 but its imposing hulk and elegant chimneys were an indelible part of the London skyline long before that. For 30 years, however, Battersea power station - Europe's largest brick building - stood abandoned as developer after developer took flight, mostly because of the cost of bringing a colossal decommissioned power station back to life.

But the 1930s Grade II listed coal-fired power station's fortunes seem finally to have been reversed. Current owners, a Malaysian consortium that includes the country's leading property developer SP Setia, came on board in 2012 at a time when there was increasing talk of demolition of the red-brick beast. They would cover the £750 million cost of the plant's revamp and transformation into offices, shops, restaurants and flats through the sale of 254 upmarket residential units within the power station building and of many more high-end homes in apartment blocks scattered across the wider 19-hectare Battersea Power Station development, some designed by Frank Gehry and Foster + Partners.

The juxtaposition of new and old, crisp modern elements and distressed original ones, is also a theme. Brick walls covered in graffiti and the imprints of staircases past are being kept as they are, with space left between the original building and the contemporary insertions, where possible. "It's about expressing the full height and fabric of the existing building," says Eyre. The all-important concrete chimneys were so badly corroded, however, that they are being demolished and rebuilt.

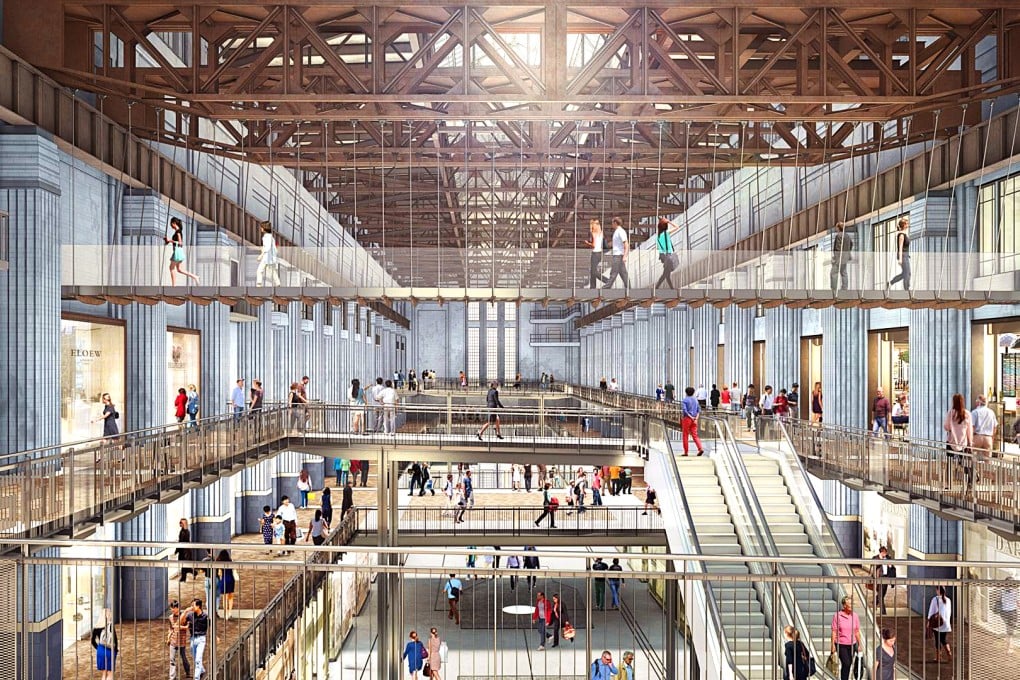

When the repurposed power station is completed - 2019 is the scheduled date - there will be much else to contemplate, including two three-storey retail galleries in the former plant's turbine halls, with shops arranged on balconies and pedestrian bridges and suspended walkways. The contrasting styles of the halls - one ornate and one more functional - are testament to their completion dates in 1933 and 1955. "People see the power station as this single building with four chimneys but actually it was built in two halves and has very different interiors," says Eyre. "Art deco on the right-hand side and pared-back austerity Britain on the left."

Above the shops will be an events space, an arthouse cinema and a 60-room hotel and, above that, in the station's former Boiler House, six floors of office space served by an 80-metre glass-roofed atrium with glass lifts, bridges and pop-out balcony boxes.