Inside ‘world’s first’ luxury resort for spinal injury victims – how designers made everything adjustable for life in a wheelchair

On a Sydney waterfront stand 17 purpose-built pavilions designed – with input from spinal injury patients – to make life as easy as possible for guests undergoing rehabilitation, and comfortable for their families

Like everyone else on holiday at a Sydney waterfront resort, guests at Sargood on Collaroy can move seamlessly from their room to the sand, splash in the sea, and surf the waves lapping at their doorstep.

Unlike the majority of other beachgoers, the only thing Sargood’s guests can’t do is stand on their own two feet. But here at Australia’s – and possibly the world’s – first luxury resort purpose built for people living with a spinal cord injury, life is lived to the full.

Six facts about Hitler’s Nazi getaway – now a luxury resort

Around the world, accessibility advocates such as Robin Shephard in Britain, and Hong Kong-based architect Thomas Schmidt, welcome such inclusiveness. But perhaps even more remarkable than the facilities offered at this property is the fact that it’s there at all. If not for community persistence, just another homogeneous high-rise might be standing instead on its prime beachfront site.

The 4,455 square metre property on Collaroy Point had been owned by Sir Frederick George Sargood, an English-born trader who in 1920 donated it as a recuperation home for Australian soldiers returning from war. Continuing the benefactor’s vision of it as a place of healing, the property became the Royal Alexandria Children’s Hospital, to house children suffering from tuberculous and polio. Later it was used as a mental health facility.

Eventually the old buildings were demolished and the government had plans to sell the land, until a community group – now the Sargood Foundation – banded together in the late 1990s to secure the site. Digging up the property’s history gave the group leverage to preserve its original intent, says Gregor Millson, the foundation’s joint chairman.

An anonymous private donor stumped up A$5.2 million to buy the site (at 25 per cent less than its zoning value at the time) and the community, recognising the need for a special place for people with spinal injury, raised A$500,000 to fund the initial design and development application. Later (in 2012) Sydney-based WMK Architecture, a firm specialising in resort and hotel architecture with projects in Australia, Papua New Guinea, and one in Shanghai, was appointed to take the project to fruition.

Review: Hong Kong sounds feature in audio therapy package at Grand Hyatt’s Plateau Spa

“The key to it was to [be able to] stay with your partner and your kids so that they are part of the rehabilitation process, and understand what they’re dealing with in relation to this new person in their life,” Millson says. “We looked around the world and could find nothing else like this for [people with] any form of disability.”

A series of workshops with spinal injury patients informed the spatial design. “We wanted it to look, feel and function like a resort that is totally bespoke to the needs of a person in a wheelchair, but can accommodate their families as well,” says Greg Barnett, managing director at WMK Architecture. This is achieved through an innovative architectural approach that Barnett says is “as far from a traditional institutional facility as imaginable”.

The resort comprises 17 self-contained pavilions with individual linear roofs that mimic the crest of a wave. Each pavilion is about 50 to 60 square metres and has the feel of a five-star hotel suite, with advanced technology making life for guests as easy as possible, Barnett explains.

For instance, furniture can be adjusted to different heights to meet the custom requirements of each user. Strategically placed windows allow guests to gaze at the stars from their king-size bed. The kitchenette includes a mechanically adjustable bench top with an integrated sink and cook top, while the bathroom “is luxurious – the antithesis of that found in a hospital or rehab unit”.

The blinds, television, lights and air conditioning are operated by remote control. Openable highlight windows allow natural light and ventilation. Each suite also has a timber deck where guests can sit outside and chat with people walking to and from the beach.

In addition to a communal lounge, there’s a restaurant-quality kitchen where guests can cook and eat, as well as a gymnasium and rooms for seminars, rehabilitation and training purposes.

On the lower level, guests can transfer to a sand wheelchair giving them access to the beach, and into the water should they choose. The facility even has a jet-powered surfboard so they can ride a wave like everyone else.

A wheelchair-friendly, 600-metre pathway has been built by the local council connecting Sargood on Collaroy to Long Reef Golf Course, one of the most picturesque in Sydney. This also houses a specially designed Paragolfer golf cart, enabling people with spinal injuries to play a round.

“We followed no rule book, gaining much of our inspiration from listening to, and interacting with, users,” Barnett says. “Even when there was an ‘Australian Standard’ we challenged it, knowing that this facility would set the tone for lifestyle care in all genres.”

The value of inclusive and accessible hotel design, both in terms of the physical structures and services on offer, was not lost on Robin Sheppard, co-founder of Bespoke Hotels, Britain’s largest independent hotel group representing more than 200 properties. This followed his own diagnosis in 2004 of Guillain-Barre syndrome, a rare and paralysing illness.

How nada yoga can destress Hongkongers. We take a 30-minute trial session to find out

“There is a profound need for properties across the industry to inject more joy into their disabled-friendly facilities, and there is a great deal more we could all be doing in terms of adjusting the hearts and minds of both staff and owners,” Sheppard says.

In 2016 his company began the Bespoke Access Awards, an international design competition that seeks original ideas to improve access and provide an enhanced experience for hotel guests, particularly for those with disabilities.

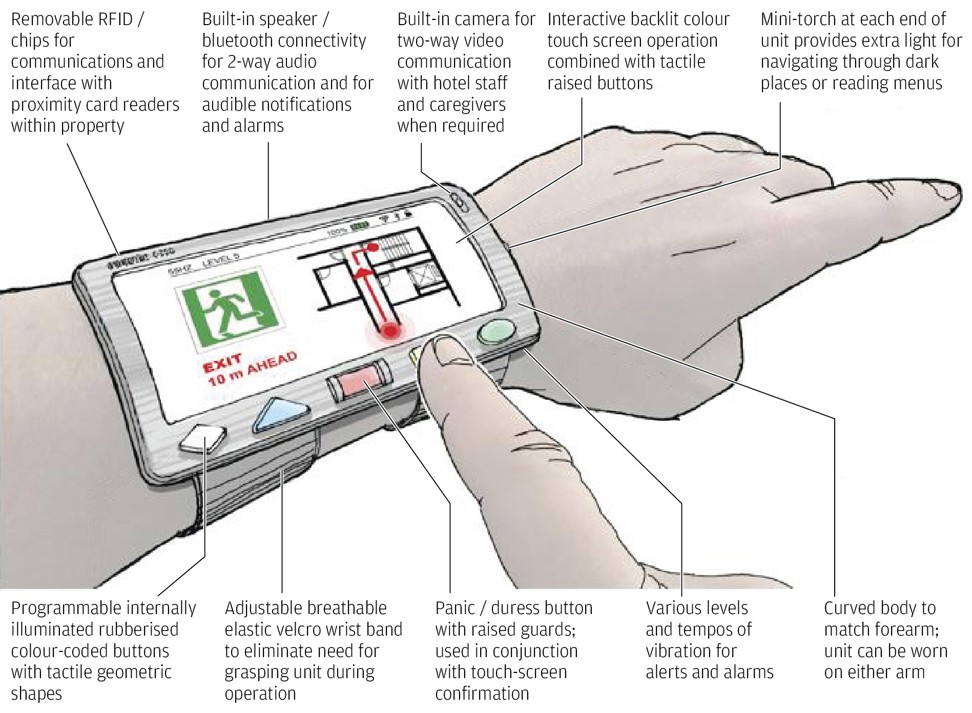

Hong Kong-based Schmidt, who specialises in hospitality design, entered the product design category of the inaugural competition with his concept for a wearable navigational aid that caters to guests with all types of disabilities. Schmidt, the founder of Sepia Design Consultants, got the idea after seeing the difficulty an elderly friend, who had Parkinson’s disease and was wheelchair-bound, faced when trying to get around Hong Kong.

His solution – still at concept stage – was a Bluetooth-connected, wrist-worn device with colour-coded tactile buttons the wearer could press to navigate the hotel and/or its surrounding area, summon help (via a panic button), access their room, and voice-assisted additions. The device could assist a wide group of people, including the visually impaired, says Schmidt.

The winning entry, submitted by Britain-based specialist accessible design company Motionspot and international design practice Ryder Architecture, was a concept called AllGo, which focused on the notion that all hotel rooms should be suitable for any guest, rather than having a designated “disabled-friendly” space within the hotel.

There is a profound need for properties across the industry to inject more joy into their disabled-friendly facilities

Ed Warner, founder of Motionspot, says that accessible hotel-room design “can be a real headache” for architects, hotel operators and users alike. Warner says the solution was for each room designed to be adaptable to the needs of the user through integrated and flexible features that can be modified before the arrival of the guest. It would enable the delivery of personalised, accessible hotel rooms across the world.

As for Sargood on Collaroy, the design that architect Greg Barnett describes as a highlight of his career is already having a profound impact on the community it serves.

A business model is followed to maintain the facility’s financial sustainability, while its ownership structure has been set up to keep the property in community hands.

A statutory body (icare New South Wales), which provided a A$15 million grant towards the building’s construction, is now 50 a per cent shareholder; the private philanthropist is a 25 per cent shareholder; and the Sargood Foundation a 25 per cent shareholder, Gregor Millson says.

Yoga on a climbing wall – exercise reaches new heights in Myanmar

“The reason for that is that we didn’t want to get into a predicament where, in 40 years’ time, someone could sell the site and have it rezoned for redevelopment when Frederick Sargood’s vision was that this would be a beautiful place for therapeutic purposes for people who need it.”