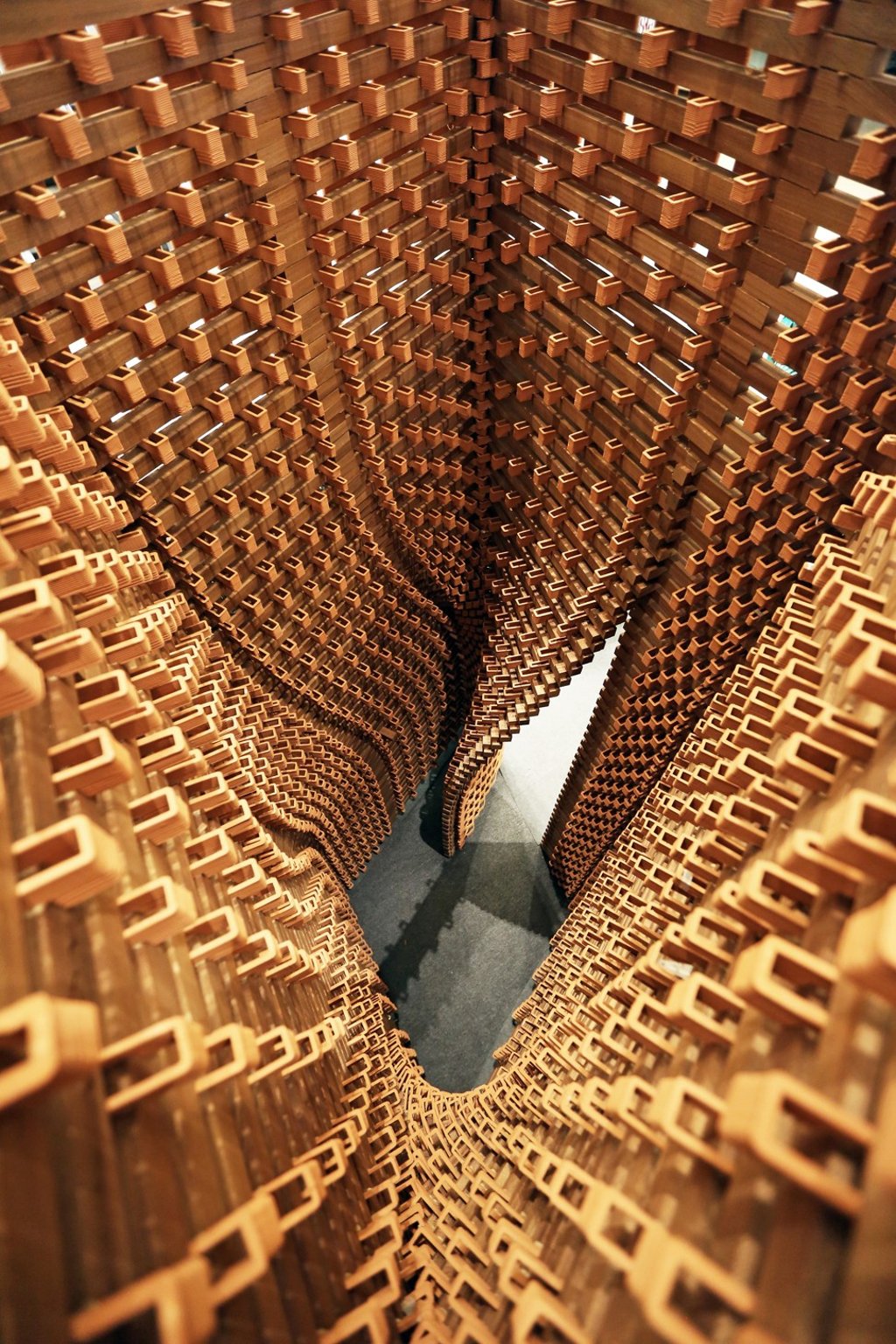

Robot makes ‘intelligent’ bricks that could reduce air conditioner usage – Hong Kong university lab’s breakthrough

Researchers at the University of Hong Kong put a robot in charge of 3D-printing bricks, which can be of any shape, and designed with cooling properties – handy for a city ‘addicted to air conditioning’

If robots can lay bricks, one of the oldest building materials used by humans, why can’t they also make bricks?

That was architect Christian Lange’s reaction 12 years ago when he saw a robot bricklayer developed by Swiss architects Fabio Gramazio and Matthias Kohler, founders of the first architectural robotic laboratory at ETH Zurich, the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, Switzerland.

And it was a thought that laid the groundwork for a robotics laboratory at the University of Hong Kong, where Lange is a senior lecturer in the school of architecture, and to a robot making 3D-printed bricks there.

French firm unveils first 3D-printed house built in 18 days by a robot

The experimental facility, called the Fabrication and Material Technologies Lab, opened in October 2016. Because of the role ceramics have played in Chinese culture, Lange, who heads the university’s robotics team, specified that its first piece of equipment should be a 3D printer that could print clay.

“Ceramic bricks and tiles have been an important building material in Hong Kong and mainland China, but in today’s world, their role has been diminished to small surface detail on a concrete tower,” says Lange.

He set about reviving “this rich history” of Chinese brick making, but with a twist: the bricks his robots would make would have the potential to transform building design and construction.