Hong Kong at Venice Biennale 2018: apartment living in focus as exhibitors look at how to create a community in a high-rise

Hong Kong’s contribution to the annual exhibition brings together 111 skyscraper models and artist impressions by 94 architects, with each exploring different ways of making high-rise living more comfortable, environmental and social

The Venice Biennale of Architecture can be an unruly affair, with 65 national pavilions and dozens of other exhibitions, each with their own agenda. This year, however, the many different parts of the world’s largest architecture showcase seem to have taken the overarching theme to heart.

The theme is “Freespace”. As described by the biennale’s curators, Irish architects Shelley McNamara and Yvonne Farrell, it is a philosophy that positions architecture around the people who use it. In their words, it represents “a generosity of spirit and a sense of humanity at the core of architecture’s agenda”.

Public land for private profit? New ‘art and design district’ next to Hong Kong harbour takes some liberties

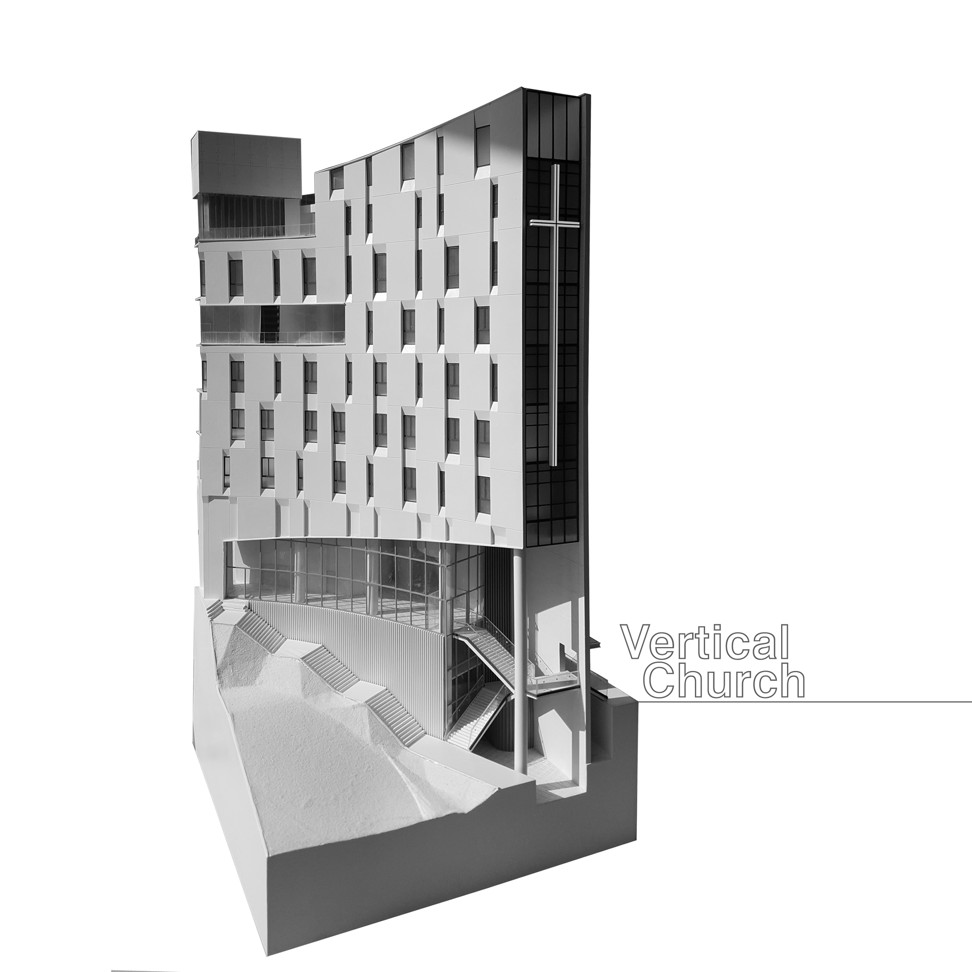

Hong Kong, as usual, took a pragmatic approach to the concept. Its exhibition – on display in a typical Venetian courtyard house next to one of the biennale’s two main venues – brings together 111 skyscraper models and artist impressions by 94 architects under the title “Vertical Fabric: density in landscape”. Each installation explores different ways of making high-rise living more comfortable, environmentally friendly, social, and humane.

Some are conceptual, while others are already under construction – including Victoria Dockside, an exhibit of the tower now being built on the Tsim Sha Tsui waterfront, and a high-rise church in Fortress Hill.

“It’s a new era for the skyscraper,” says Italian architect Giusi Ciotoli, whose 2017 book Dal grattacielo al tessuto verticale (From skyscrapers to vertical fabric) inspired the name of the Hong Kong exhibition.

Although cities around the world are embracing high-rises as a vehicle for increased density, their fundamental form hasn’t changed in more than a century and their problems are multiplying, says Ciotoli – as anyone living in a cramped Hong Kong flat can attest. “If you believe in the human possibility of the skyscraper” – rather than simply the profit possibilities – “it’s a different way of seeing these towers”, he says.

Six ways to solve Hong Kong housing problem – from water pipes to plastic bottles

University of Hong Kong architecture professor Wang Weijen, who curated “Vertical Fabric” along with architects Thomas Chung and Thomas Tsang, as well as managing curator Grace Cheng, says he chose to focus on high-rises precisely because they are globally relevant. “It’s not just about representing Hong Kong – it’s about saying something about architecture and the human condition,” he says.

There is certainly something universal about towers, even if most cities do not have as many of them as Hong Kong. The backdrop of “Vertical Fabric” is a mural by Chinese artist Qiu Zhijie that explores the history of towers. Starting with mythical structures like the Tower of Babel, it then passes by Chinese pagodas and church towers until it reaches the modern skyscrapers that emerged after the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. It’s meant to illustrate that “the tower is not just part of the modern condition”, says Thomas Tsang.

What is distinctly modern is the ability to create complex, multifaceted towers that bring together many different uses – “microcosms of the city”, as Ciotoli describes them. Harnessing technical innovations for a better quality of life is a thread that runs through the exhibition. “Each one challenges the status quo of towers in Hong Kong,” says Wang. “Many of them are based on a concern for public space, common space.”

Wang has three conceptual projects in the exhibition. One, Fabricating Porosity, creates a kind of wind shaft that allows the tower to be naturally ventilated, reducing the energy consumption needed for air conditioning. Fabricating Porosity and Stepping-Up Patios both explore the need for more public and communal spaces in skyscrapers, creating neighbourhood-like structures rather than silos.

In the latter installation, high-rise residents must pass through open-air patios on their way home, creating opportunities for them to bump into neighbours – and for street life to take place in the sky.

Winy Maas, co-founder of Dutch architecture firm MVRDV, which contributed to the exhibition, describes Vertical Fabric’s collection of skyscrapers as a “collective yell” for difference and creativity.

“We need [densely populated] areas on the planet,” but density needs to be well designed and well managed if it is to be effective, he says. His own project, Avatar 2.0, knits together four towers through a complex system of footbridges that he describes as a “beautiful web” that replicates the ground-level network of a city. Some of the skybridges are connected by stairs and waterfalls to create “three-dimensional parks”.

Botanist and vertical garden pioneer Patrick Blanc talks about the birth of his growing business and how to create a natural ecosystem

Jason Carlow, an architect previously based in Hong Kong who now lives near Dubai, proposed the Prefab Pencil Tower, which offers a practical way of dealing with Hong Kong’s flat sizes and soaring property values. By exploiting a loophole in Hong Kong’s building code that allows for prefabricated facade elements, like bay windows, to be exempt from a building’s gross floor area, Carlow creates modular living spaces built directly into the facade. This allows for even the skinniest of towers to have larger, more flexible housing units.

In the Living Tower , Hong Kong-based architects Sarah Lee and Yutaka Yano address issues of sustainability by covering the tower in photovoltaic cells so it can generate its own energy, along with harvesting water and providing space for urban farming.

Some of the towers are purely conceptual, like Birds’ Monastery, a birdhouse imagined by Korean architect Seung H-sang, or Primitive City, a series of stacked single-family homes created by Japanese architect Jun Igarashi. But some have already been built, while others are under construction. Victoria Dockside, a 66-storey tower on the Tsim Sha Tsui waterfront, will bring together apartments, hotel rooms, offices and cultural space in a terraced layout that allows each of the different uses to exist independently while also being connected.

I really believe that architecture should be related to life. And sometimes, architecture helps us discover that life

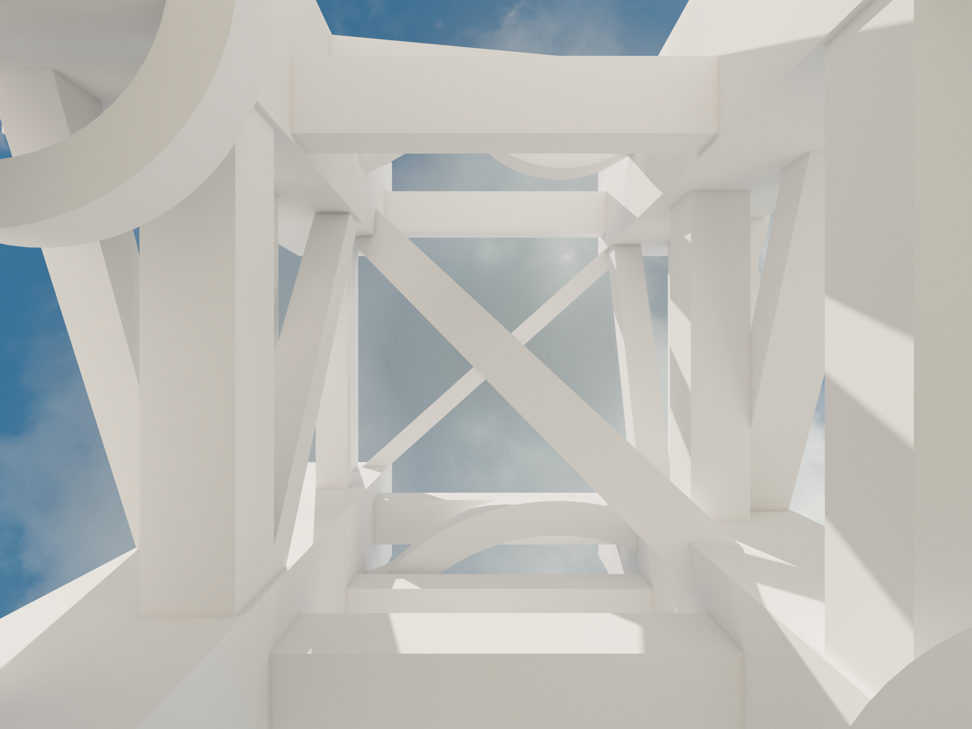

AGC Architects’ Vertical Church, that’s currently under construction in Fortress Hill, uses abundant natural light and a rooftop chapel to incorporate a number of different community and religious uses without losing the sacred atmosphere of a church.

The diversity of these concepts led to praise from some of the architects, curators and others who visited “Vertical Fabric” during its preview in late May. But a discussion forum held in the courtyard also raised critical points. Donald Choi, an architect who is also the executive director and CEO of Chinachem Group, a leading property developer in Hong Kong, expressed frustration at Hong Kong’s general aversion to thinking outside the box – or in this case, the towering rectangle.

“Hong Kong is no more commercial a city than New York or London, but in terms of the quality of architecture we produce, we are falling behind,” he says. “We have to ask the question, how do we want to impact community and society in our work?”

Prada Tower unveiled at Milan Design Week ‘explores effect of space on art’

That’s a question considered more explicitly by other exhibitions. The Philippines’ exhibition, “The City Who Had Two Navels”, looks at the twin impact of colonialism and neoliberalism on that country’s cities. Canada’s exhibition, “Unceded”, exposes the philosophy of indigenous architects who believe in working closely with nature and community. Hungary’s “Liberty Bridge” examines how a landmark river crossing in Budapest has served as a stage for spontaneous public uprisings.

In contrast to the official China pavilion, which showcases projects that aim to modernise the countryside, a satellite exhibition called “Across Chinese Cities: Community”, organised by Beijing Design Week, highlights grass roots rural and urban projects. “They are living projects, not just a piece of architecture that has been built,” says curator Bea Leanza. “They are about the people. They aren’t architectural statements that can be easily abandoned.”

Singapore’s exhibition, “No More Free Space?” highlights 12 projects that deal in creative ways with some of the city state’s constraints, including a limited amount of land area and a sweltering tropical climate. Enabling Village draws from Singapore’s pre-colonial kampongs (villages) to create a community gathering space for disabled people; Lucky Shophouse is a historic bookstore that was converted into a flat that conserves its heritage value. All of the projects put the needs and experiences of their users above other considerations. “We’re talking about the qualitative aspect of architecture and not the quantitative aspect,” says curator Wu Yen Yen.

Chinese architect and Zaha Hadid protégé celebrates the beauty of nature in his urban designs

That attitude underpins Japan’s national exhibition, “Architectural Ethnography”. Curated by Momoyo Kaijima, co-founder of architecture firm Atelier Bow-Wow, the show is a collection of drawings that contemplate the everyday life of urban spaces in Japan and beyond. Among the renderings of ordinary houses and cityscapes are four projects that deal with Hong Kong, including a survey of the city’s building types by Swiss architects Emanuel Christ and Christoph Gantenbein, and an illustrated depiction of the “umbrella movement” protests on Harcourt Road in 2014.

“I really believe that architecture should be related to life,” says Kaijima. “And sometimes, architecture helps us discover that life.”

The Venice Architecture Biennale 2018 continues until November 25.