Designer of Shanghai’s 1000 Trees development, Google’s new London HQ, Coal Drops Yard and Singapore’s The Hive on connecting to the human scale

- British designer Thomas Heatherwick, one of the few recognisable Western designers in Asia, says large projects need to integrate with the human experience

- His 1000 Trees project in Shanghai is almost revolutionary in the context of Chinese urban planning

Heatherwick Studio is hidden behind a grand Victorian frontage down a side alley in a converted industrial building in central London. It is almost impossible to find unless you spot the battered Citroen 2CV parked outside, a quirky design classic that sums up the essence of Thomas Heatherwick’s design output: surprising, unconventional and yet compellingly timeless.

Like the Citroen, Heatherwick’s designs are often more popular with real people than critics. With or without the design establishment’s support, his influence continues to grow worldwide.

The office is close to one of the biggest redevelopment projects in Europe at Kings Cross railway station, where two of Heatherwick’s most significant recent projects are situated: Coal Drops Yard, London’s newest shopping and dining district, and the new Google headquarters, designed in collaboration with Danish architect Bjarke Ingels. These are just two prestigious projects to add to a portfolio of remarkable innovation over 25 years.

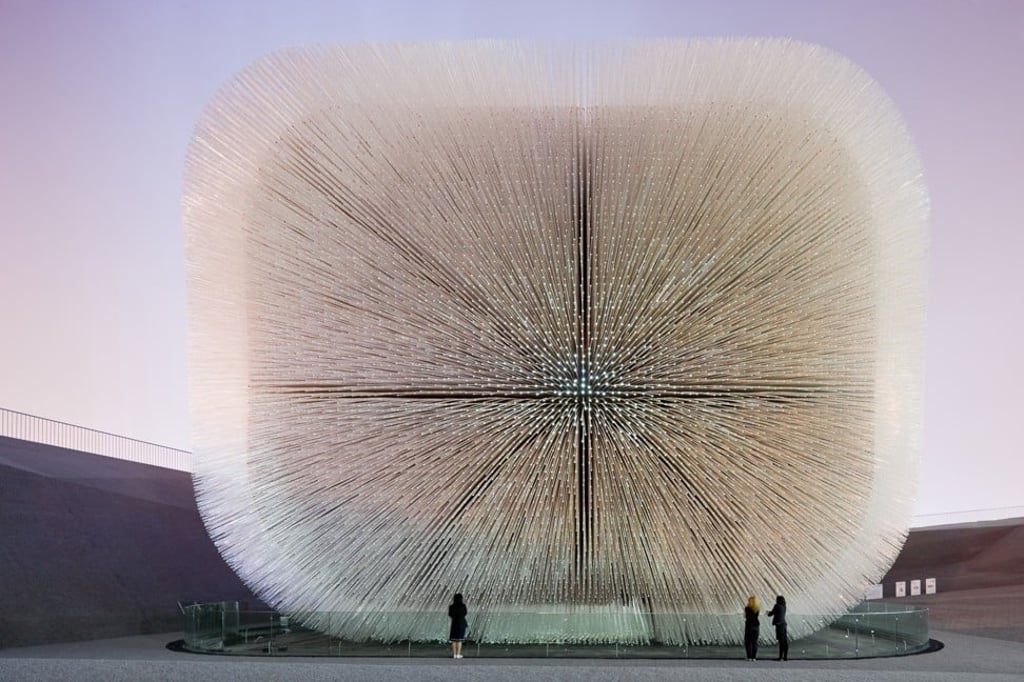

Heatherwick is now a globally recognised designer and one of the few recognisable Western designers in Asia. Since his UK Pavilion (known as the Seed Cathedral) was voted the best national pavilion at the Shanghai World Expo in 2010, he has picked up a number of prestigious commissions in Asia, including the Learning Hub (also known as The Hive) at Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University, opened in 2015.