Explainer | Busan International Film Festival: the history, the scandals and the winners at Korea’s ‘Cannes of Asia’

- As Korea’s major international film festival returns with a full programme, we look back at the highs and lows of the ‘Cannes of Asia’

- From the Sewol ferry disaster documentary that led to boycotts, funding cuts and a resignation, to hit films premiered at Busan, here’s all you need to know

The Busan International Film Festival (BIFF) will be back for its 27th edition on October 5, returning to full strength after a couple of hybrid events held during the earlier stages of the coronavirus pandemic.

With a broad programme featuring 243 films from 71 countries, the festival will once again put on a full roster of physical screenings and host a large complement of international guests. Also returning will be a variety of events and programmes which had been paused for the Covid-19 pandemic.

Often called the “Cannes of Asia”, BIFF has been a cultural landmark, known both for introducing and incubating new talents who have gone on to become leading voices in Asian cinema.

Established in 1996 in the lively southern port city of Busan, South Korea’s second largest metropolis, the festival’s history mirrors that of the modern Korean film industry, which emerged as an international powerhouse in the late 1990s.

Formerly split across the lively Nampo-dong neighbourhood, the former downtown of Busan, and the beachside tourist hub of Haeundae, BIFF now unspools in the shadows of sleek skyscrapers in the ultra-modern Centum City neighbourhood.

Most screening venues are within a five-minute walk of the Busan Cinema Centre, a feat of engineering which boasts the longest cantilever roof in the world. Serving as the official hub of BIFF, but open year-round, the complex was unveiled in 2011, in time for the festival’s 16th edition.

‘I knew we had something special’: Malaysian filmmaker on Swiss festival win

Welcoming around 200,000 visitors a year (a number which dropped to 20,000 in 2020 and rebounded to 76,000 last year), BIFF is by far the largest festival in South Korea and attracts leading lights from the East and West, from Tony Leung Chiu-wai, this year’s Asian filmmaker of the year honoree, to Quentin Tarantino, who dropped in for a surprise open talk with Bong Joon-ho in 2013.

While the festival has long been celebrated by the local and international film community, it hasn’t been immune to controversy. Over the years it has been forced to weather several scandals, notably when its progressive agenda has clashed with conservative political powers.

The most significant of those began during BIFF’s 19th edition in 2014, when the festival premiered The Truth Shall Not Sink with Sewol, an explosive local documentary directed by Lee Sang-ho and Ahn Hae-ryong which condemned the government’s emergency response to the sinking of the MV Sewol ferry in April of the same year that claimed the lives of 304 people, many of them teenagers, and traumatised the nation.

Suh Byung-soo, the mayor of Busan at the time, and thus automatically a board member of BIFF, which partly relies on government funding, urged the festival to remove the controversial film from its line-up. However, the screening went ahead as planned.

The contentious aftermath saw the festival trying to defend its freedom of expression, while the city of Busan slashed its funding. In 2016, festival director Lee Yong-kwan was forced to step down.

Various Korean film associations decided to boycott BIFF to object to the government’s meddling in the event and it wasn’t until after the impeachment of President Park Geun-hye in 2017 that things began to improve. Lee was eventually reappointed as the festival director in time for the 2018 edition.

Naturally, as a Korean festival, much of the focus has also been on local films. BIFF screens between 40 and 60 Korean features per year, many of them world premieres.

However, these are major films with big stars which were destined for release anyway. BIFF’s most important contribution to cinema is the new talents it discovers.

Among the stand-out indie films that have debuted at the festival before going on to receive global acclaim are Park Jung-bum’s intimate North Korean defector drama The Journals of Musan, O Muel’s stark Jeju Massacre tale Jiseul set during a 1948 uprising on South Korea’s Jeju island, Lee Su-jin’s devastating abuse drama Han Gong-ju and Kim Bo-ra’s soaring coming-of-age tale House of Hummingbird.

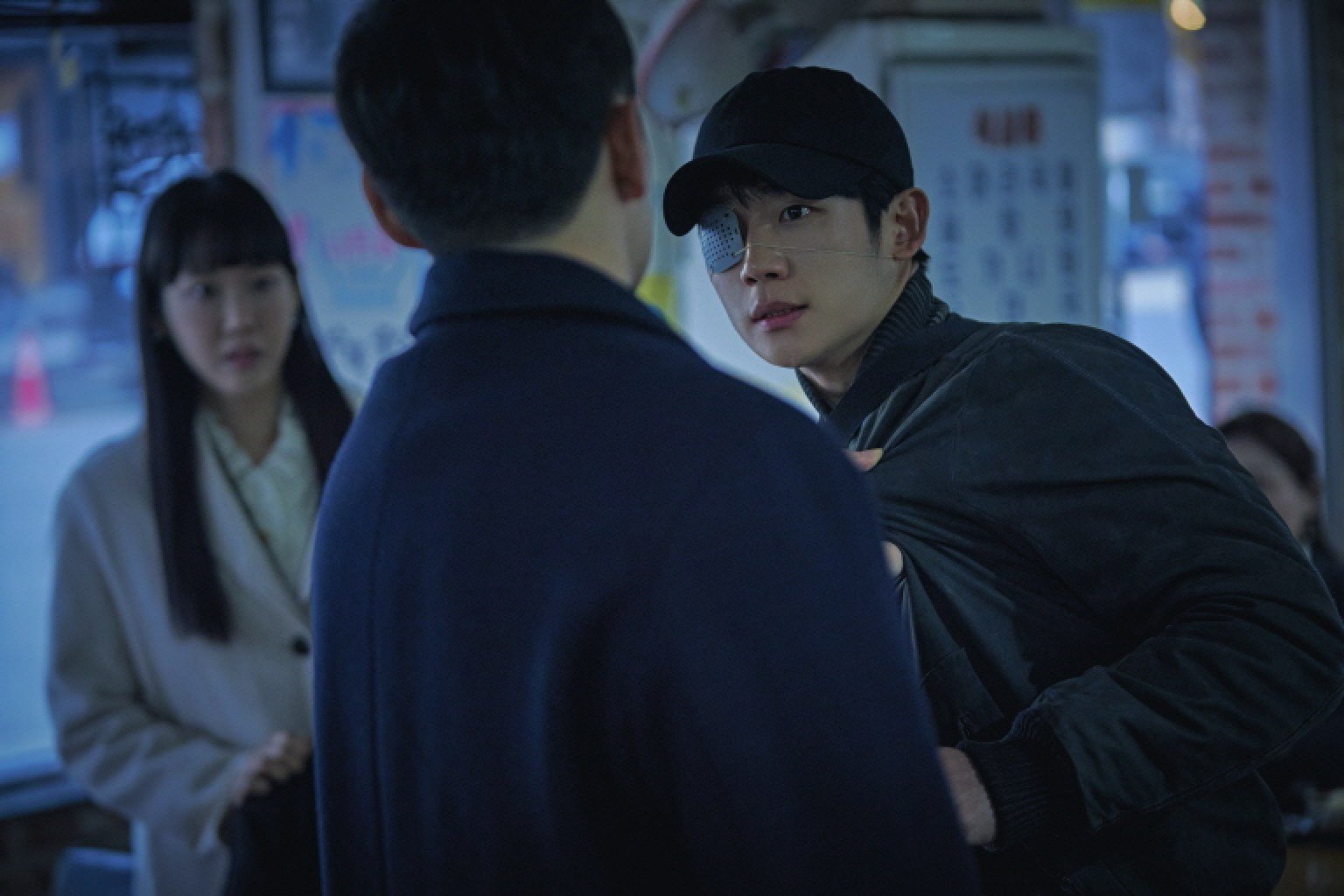

This year’s 27th edition promises a cornucopia of cinematic delights, and quite a few small-screen wonders. After launching last year, the On Screen programme for TV dramas has tripled this year. Among the shows on the docket are the Disney+ show Connect, Japanese filmmaker Takashi Miike’s first Korean drama.

But as ever, BIFF’s gems will likely be the ones we don’t see coming – the new films from young voices plucked from obscurity by the festival’s programming team.

For adventurous cinephiles, discoveries await in the festival’s signature New Currents and Korean Cinema Today-Vision programmes, the competition sections reserved for debut and second-year works by Asian and Korean filmmakers.