John Fogerty digs deep and releases a lifetime of bitterness in his bestselling memoir

The Creedence Clearwater Revival frontman, whose abrasive baritone is one of the stand-out voices of the golden age of rock, explains how he had to learn to let go of the past

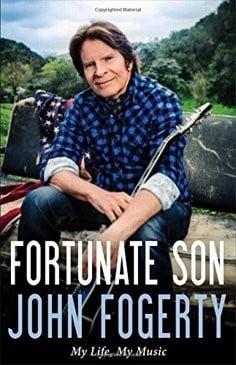

Fogerty, whose memoir, Fortunate Son, debuted on The New York Times’ bestsellers list in November, laughs heartily. “As a kid, I thought Vegas was for old people; now that I’m 70, I suppose there’s some truth to that,” he says. “But I don’t feel I’m forsaking my vision of the 23-year-old who played Woodstock in 1969.”

The man who wrote and sang such classic songs as Proud Mary, Born on the Bayou, Down on the Corner and Centerfield laughs again.

“It is pretty funny to me,” Fogerty acknowledges of his pending debut residency in Sin City. “When I used to think of Vegas, I’d think of [comedian] Shecky Greene. He always wore a plaid sports coat, or a tuxedo. And it seemed impossible to me, even 10 years ago, I’d ever play there.

“But I know my audience has changed. So have I. And so has Vegas. Because the people who are going to come see me there, many of them were the same people who would have seen me at Woodstock. So it’s kind of OK. I don’t think there’s a built-in prejudice against Vegas any more. And I’ll certainly be doing my show, which is rock’n’roll. I’m not going to be doing it with half-naked girls and dancing elephants. When Cher does a Vegas show, she probably changes costumes 14 times. I don’t have any costumes.”

The advertising tag for Fogerty’s run at The Venetian Theatre, “Peace, Love & Creedence”, evokes Woodstock’s “3 Days of Peace, Love & Music”. But this 1993 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductee devotes barely two of Fortunate Son’s 406 pages to that iconic music festival. And his memories of the generation-defining event are anything but rosy in his extremely candid book.