Contraptions and implants for the wannabe cyborg

While true brain melding may be a long way off, a series of experiments and advances are steps in the right direction

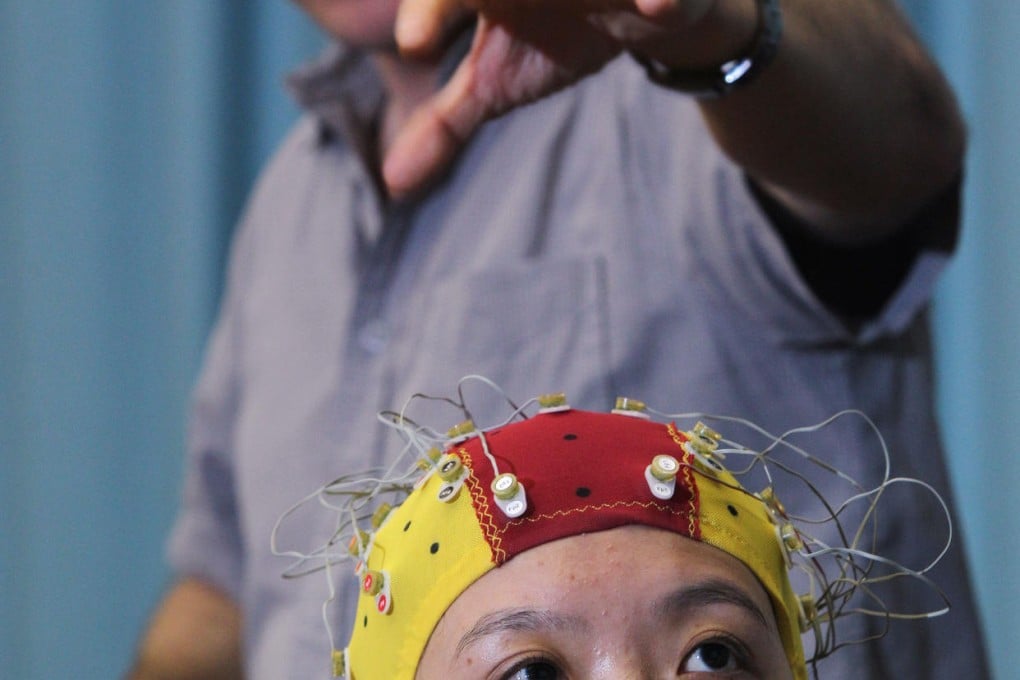

Last month, a couple of guys wearing swim caps fitted with electrodes made news for establishing a connection between their brains. Over-excited headline writers even cited "Vulcan mind melds", as if one could read the other's mind, much as Star Trek's Mr Spock experiences memories in other beings.

The reality was far from a mind meld. One of the two men - Professor Rajesh Rao of the University of Washington - was sitting playing a computer game with his mind. Electrical signals from his brain were transmitted to a colleague, Dr Andrea Stocco, who was seated at a computer across campus. At one point, Rao imagined using his right hand to click a button, and Stocco promptly hit the space bar on his keyboard.

"The internet was a way to connect computers and now it can be a way to connect brains," said Stocco.

Or, as at least one dismissive neuroscientist suggested, the claimed first ever brain-to-brain interface was just a "publicity stunt", and we are still very far from really connecting brains via the internet. The reality is probably somewhere in between and the finger-stirring experiment may prove a small step towards a future in which humans increasingly interface with and via computers.

It's by no means the only step that has been taken, as recent years have seen a flurry of reports on projects involving connections between computers and brains. And not always human brains.

Early this year came a report on two rats - one at Duke University in the US, the other at the International Institute for Neuroscience of Natal in Brazil - that unwittingly co-operated on a task, thanks to a link between implants in their brains. One rat, the leader, was trained to press one of two levers that resulted in it being rewarded with water. Its follower faced similar levers and could then respond to a signal - feeling like a tingle in its brain - and choose which of them to press. If the follower chose correctly, both it and the leader were rewarded and soon the long-range partnership led to the follower choosing correctly up to 70 per cent of the time.

Another experiment, at Harvard Medical School in the US, linked rat and human brains without the need of implants. Human volunteers were fitted with electrodes to record brainwaves and could then decide when to send a signal that would make a rat's tail move. This signal was relayed to an anaesthetised rat using ultrasound focused on its brain's motor cortex and, 95 per cent of the time, the rat's tail indeed wagged as instructed.