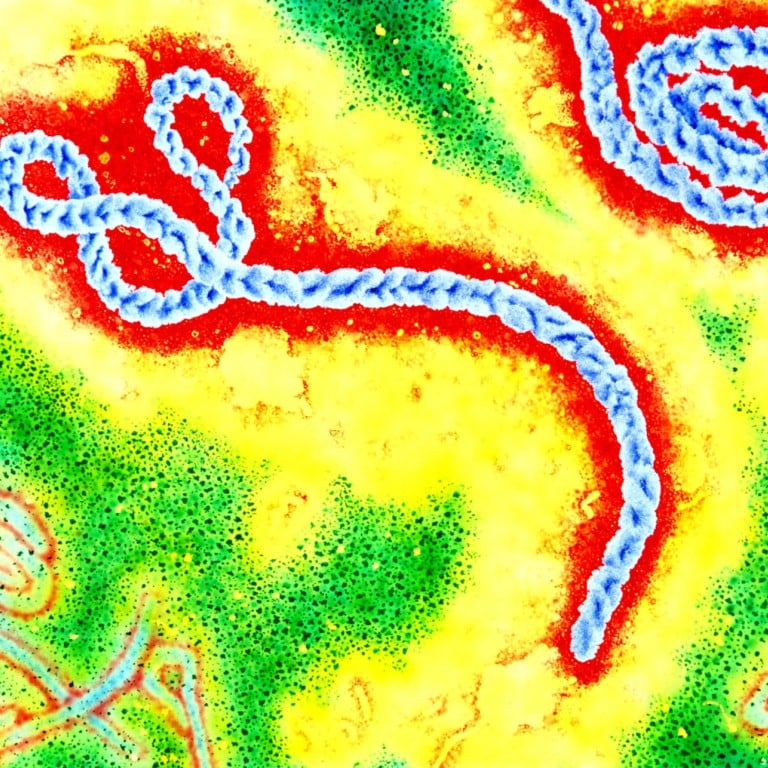

Scientists are closing in on drugs that may stop the deadly Ebola virus

Disease still kills 90pc of its victims, four decades after emerging, but treatments entering the trial stage may change that frightening statistic

Almost 40 years after Ebola emerged from the jungles of Africa as one of the world's most lethal diseases, scientists are beginning to close in on treatments that may be able to stop the virus.

The relative rarity of Ebola outbreaks, and the fact that they are largely limited to rural areas of poor African nations, makes the disease an unattractive target for big drugmakers. Instead, much of the research has been funded by the US government. Tekmira Pharmaceuticals, for example, began its first human trial of a drug in January with backing from the Defence Department.

"There are already candidate cocktails that can be used in an emergency," said Erica Saphire, a professor at the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California, who is leading a consortium of 15 public and private institutions to develop treatments to fight the virus. "It's a really exciting time to be working on Ebola."

The WHO had not requested emergency use of any experimental treatments that had not been through the necessary clinical tests, said Tarik Jasarevic, a spokesman for the Geneva-based agency.

Trials showing the drugs were safe, plus ethical and regulatory clearance from the health ministries of affected countries, and regulatory clearance from the country where the drug was made, would be needed before any experimental treatments could be used in an emergency situation, said David Heymann, a professor of infectious disease epidemiology at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. He has worked on Ebola since the first outbreak in 1976.

Ebola is so deadly and so contagious that it poses a risk to national security, according to the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. The agency lists the virus as a Category A bioterrorism agent, alongside anthrax and smallpox.

Tekmira's product, known as TKM-Ebola, is being developed under a US$140 million contract with the Defence Department. Tekmira, based in Canada, this month won fast-track designation from the US Food and Drug Administration to develop the experimental treatment.

While HIV, the Aids-causing virus that also jumped from animals to humans in Africa, had spawned dozens of approved drugs and a US$14 billion market, the small number of Ebola cases was a deterrent for big drug companies, said Stephan Guenther, head of the Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine in Hamburg, Germany.

"If you count all the cases of Ebola since the discovery, it's below 10,000, so it's definitely not of commercial interest," he said.

Guenther led a team of researchers that showed an experimental treatment called favipiravir, developed by Fujifilm's Toyama Chemical unit as a flu treatment, cleared Ebola virus and prevented mice from dying in a study published in February.

Still, there was no clear path to commercialisation, given the challenge of testing the drug in humans, said Yoshinobu Izumi, a spokesman for the unit.

Among the most promising drugs in development are antibody cocktails. One was being developed at Canada's National Microbiology Laboratory, though it needed more work before it could be tested in humans, Public Health Canada said.

Mapp Biopharmaceutical, a closely held company in San Diego, is developing another, along with the Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency, the NIH and the Defence Threat Reduction Agency.

That cocktail prevented 43 per cent of monkeys with symptoms of Ebola from dying in a study published last year in . Previous studies showed the treatment, called MB-003, saved all of the monkeys when given an hour after exposure to the virus, and two-thirds of them when administered 48 hours after exposure.

The virus can cause sudden fever and intense weakness, which is followed by vomiting, diarrhoea and internal and external haemorrhaging. The disease has a fatality rate of as much as 90 per cent, making it one of the most feared infectious diseases.

People could also get infected during burial ceremonies involving close contact with the bodies of people who succumbed to the disease, Jasarevic said.

The deadliest recorded outbreak was in Congo in 1995, when 254 of the 315 people infected died, according to the WHO. All the outbreaks in the past decade have been in Congo, the neighbouring country of Congo-Brazzaville, and Uganda, with the exception of one outbreak in Sudan in 2004.

The WHO was not recommending any restrictions on travel to Guinea, Jasarevic said. Outbreaks usually started in remote villages where people had contact with infected animals, and rarely spread because the disease did its damage so quickly, he said.

"Experience shows that there is a low risk for travellers," he said. "People who get Ebola tend to get very sick very fast, and they are not really able to travel. That's why these outbreaks usually are self-contained."