Stories behind Hong Kong districts: SoHo before the escalator

For most of its history SoHo was a quiet residential area with a multicultural mix of people. When the Central–Mid-Levels escalator opened in 1993 the neighbourhood turned into a dining hub

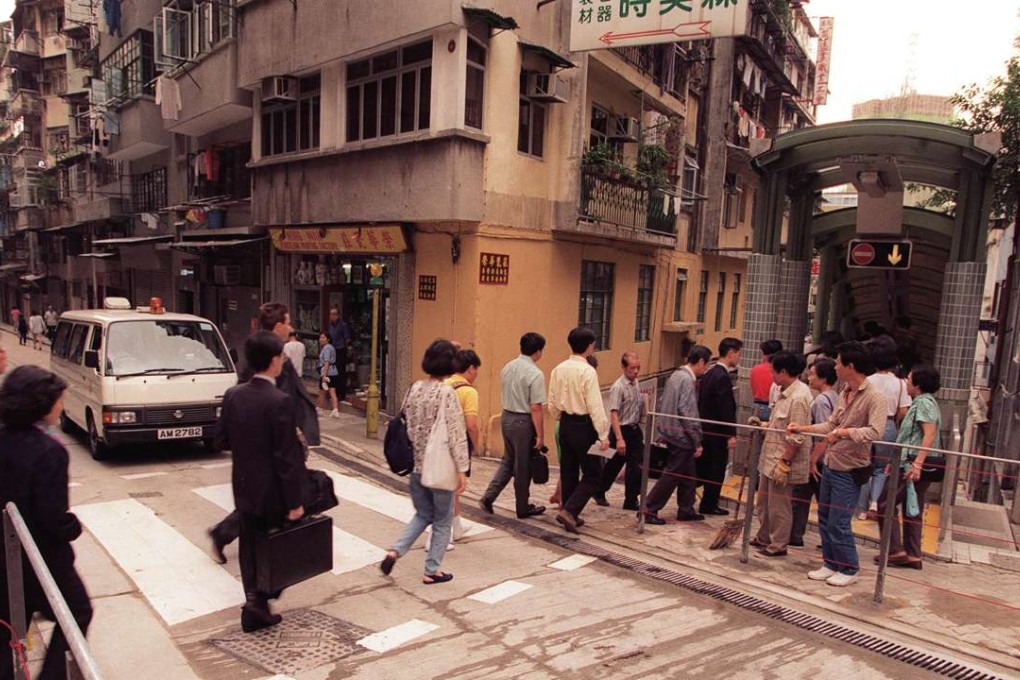

Neighbourhoods don’t take long to become established. Just about everyone in Hong Kong knows SoHo as a popular destination for eating and drinking, but its history as an entertainment district reaches back only 20 years, when a few pioneering restaurateurs staked a claim on the streets near the newly built Central–Mid-Levels Escalator – initially in and around Staunton Street.

But it was effective. “SoHo makes a name as action escalates,” read a cheeky headline in a 1997 edition of the South China Morning Post. The article, by Kate Whitehead, described a hypothetical bar crawl that began in Lan Kwai Fong, passed through Wyndham Street, travelled up the escalator and ended with a nightcap on Staunton Street. “Sounds inconceivable?” asked Whitehead. “We’re almost there: this is the future.”

Whitehead was most certainly right. But what was south of Hollywood Road before SoHo – before the escalator opened and changed everything?

For most of its history, the area was rather anonymous, a point of transition between the bustling market district around Graham Street and the genteel mansions and apartment houses of Mid-Levels.