Couple who’ll walk, climb and swim around Hong Kong Island to create the city’s first map of coastal pollution

Scrambling and swimming, Paul Niel and Esther Röling will make a complete circuit of the Hong Kong Island shore, taking water samples as they go to map water quality and biodiversity

Curious lifeguards and fishermen watch as Paul Niel and Esther Röling leap from rock to rock around the cliffs at Chung Hom Kok beach. They are “coasteering”, and on their last reconnaissance mission before embarking on the “Round The Island – Hong Kong” expedition later this month. Their goal? To climb, scramble and swim their way around the entire island, taking water measurements as they go, to create Hong Kong’s first full coastal pollution map.

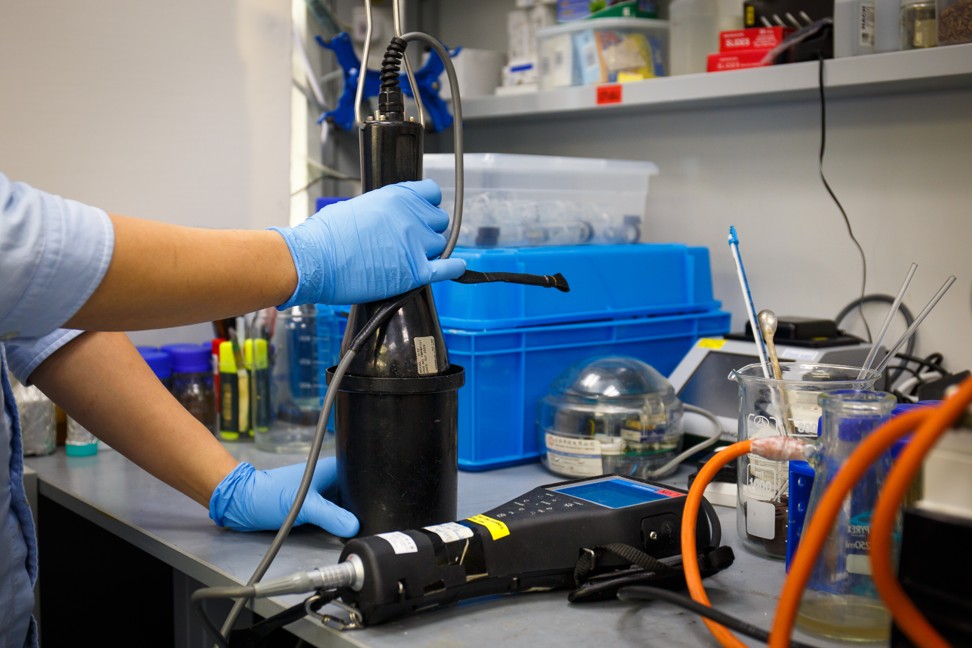

A team from the Open University is lending them a portable measuring device to map water quality and microbiodiversity, which will enable researchers to determine the effect of pollution on algae and plankton.

The couple have been on several overseas climbing expeditions, but when their daughter was born 15 months ago, they began looking for adventures closer to home.

“I found my wife Esther here in Hong Kong and we started our family here, so it’s a place that I associate very closely with,” says Niel, an Austrian mountaineer and adventurer who has climbed the highest peaks on every continent. “I always wanted to do something here, and this will be our first proper expedition project together.”

Röling, a chef and food consultant from Holland, says they’ve been shocked by the amount of rubbish and pollution since they began scouting the city’s shores last November. “It’s crazy what you see climbing around the island,” she says. “There’s so much polystyrene, plastic, tyres – even chairs and fridges.”

In pictures: the tide of trash swamping Hong Kong beaches, the volunteer cleanup and the hidden island dump causing it

Researchers say a detailed study of the coastline on such a scale has never been done before.

“Government studies are limited mainly to annual offshore sampling,” says Dr Wong Yee-keung, an assistant professor of applied science and environmental studies at the Open University. “But this will reflect the pollution along the actual coastline, so it’s very different.”

Lecturer and fellow team member Dr Tang Chin-cheung says it will be the first high-resolution baseline study conducted in the city. “I will be very interested to look at the diversity, especially of the smallest organisms at the bottom of the food chain, such as phytoplankton and zooplankton,” he says.

Niel says he has seen a wide variety of life along the coast. “We see lots of big birds, crabs, sea urchins, jellyfish,” he says. “A friend of ours spotted a reef shark the other day while coasteering here in Chung Hom Kok.”

Coasteering, which combines elements of free climbing and open water swimming, will enable Niel and Röling to access areas that researchers wouldn’t usually reach. The couple make it look deceptively easy, but following them around the rocks for a couple of hours gives an idea of the mental and physical exertion required, and the task ahead.

Above all, it will be an endurance challenge. They estimate it will take six to seven 10-hour days to circumnavigate the island, sleeping out in bivvy bags on wet, barnacled cliffs and rubbish-strewn beaches along the way.

“The main challenge will be to not get injured,” says Niel. “And that comes down to staying concentrated for hour after hour.

“Last week there was a lot of swell, and I stepped over a rock, I got caught by a wave and I got see-sawed over some barnacles. I was joking about it at first, but four hours later at dinner it swelled up to double the size and I could not lift my leg for eight hours.”

Röling, who grew up in the Netherlands, which is flat, says her challenge is trusting in her feet. “The moment you start hesitating, that’s when you fall. Especially when the tiredness sets in.”

Rest is essential because decision-making is an important part of coasteering. “With some steep or high traverses, even if there’s big swell, it’s probably safer to swim through the crashing waves than to climb 15 metres up, because if you lose your grip you’re basically finished,” says Niel. “In the waves, if you time it right, you can always swim out into the open ocean and assess the situation. So this is a very interesting side to coasteering: there are multiple solutions to every problem.”

It’s probably safer to swim through the crashing waves than to climb 15 metres up, because if you lose your grip you’re basically finished

The most worrying section is Cape D’Aguilar, because of the heavy swell. But there are urban risks, too. “We tried to do an urban section in the harbour but it finishes at one of the high-rise buildings,” says Niel. “And they’ve built a fence into the water with razor wire.”

He adds there will undoubtedly be other inaccessible areas. “Clearly, there are places like police buildings, government buildings that we can’t go around. If people put barbed wire around them, then it’s usually for a reason.”

“In this case we will simply stay as close as we can to the water, and make the measurements as often as we can,” says Röling.

The couple have taken a wilderness first aid course, and will have a boat following them, communicating with them via marine radio, and providing supplies and water.

There are logistical hurdles for the climbers, too. The university’s measuring device is bulky, and the water samples will add significant weight to their backpacks.

“We will lend them the water quality checker so they can instantly check physical parameters of the water – for example the temperature, pH, salinity – then they’ll bring some samples back for us to check more details, such as chemical content, biological diversity,” says Tang.

This will allow the team to monitor the effects of global warming on the water’s temperature, but also alert them to dangerous toxicity levels. “It will allow us to warn the government when an algae bloom is approaching – due to pollution,” says Wong. “When there’s not good sewage treatment management, it triggers this. The major concern is that some algae are toxic; only a small amount can kill fish. It’s very harmful – not only to fish but also to people in Hong Kong who eat the fish.”

Stem the red tide: researchers say human pollution is behind algal blooms and government should take charge

Tang says that as coastal areas of Hong Kong become increasingly developed, concern is focused

mainly on protecting key species such as the Chinese white dolphin or the horseshoe crab. “But we’re really lacking concern about the microorganisms at the bottom of the food chain. We need to conserve the whole habitat,” he says.

It’s not just the scientists who are excited about the expedition. As Niel and Röling trace the island’s edges, they’ll find clues about Hong Kong’s past that will provide a unique historical portrait of the island, says Stephen Davies, a maritime historian at the University of Hong Kong.

“There’s an amazing amount of history around Hong Kong’s shoreline,” says Davies. “It’s hard to spot stuff when you’re patrolling the coast or going along any kind of footpath. And to get down and dirty, really close to the coastline, is something that no ordinary researcher does – because it’s bloody dangerous.

“They may actually find stuff that we didn’t know about,” he adds. “Pillboxes, searchlight emplacements – we think we know about all of them. But who knows what might be perching as a little bit of ruin somewhere along the coastline that we didn’t know about?”

The coastline is an interesting metaphor for all the contrasts that comprise Hong Kong Island, says Niel. “We’ve passed everything from pillboxes and ruins to glittering skyscrapers in the harbour, shanty towns and squatter huts to luxury apartments in Repulse Bay.”

“Most people who come to Hong Kong for the first time – myself included – have no idea of what’s out there,” says Röling. “The nature, adventure, greenery, beautiful trails, beaches. They only see the concrete jungle.”

Niel and Röling are also members of the US-based Explorers Club, and their coasteering adventure will be the local chapter’s first science-based field expedition in Hong Kong. They’re also planning pop-up events with local schools along the expedition route, in collaboration with the Royal Geographical Society Schools Outreach Programme.

“Not only do we want to make children more aware of Hong Kong’s pollution, but also about the amazing adventures they can have outdoors,” says Niel. “Even if it motivates just two kids to venture out more, then we’ll have already achieved something.”

The Post will be tracking the expedition next week, check in with us via Facebook for updates.