How Hong Kong estate once home to Jackie Chan helped change the course of housing development in the city

Ferry Point was pioneering – a place for the emerging middle class, including actors Sammo Hung, Stephen Chow and Jackie Chan – but also the last of its kind, spurring building code changes that led to today’s skinny tower blocks

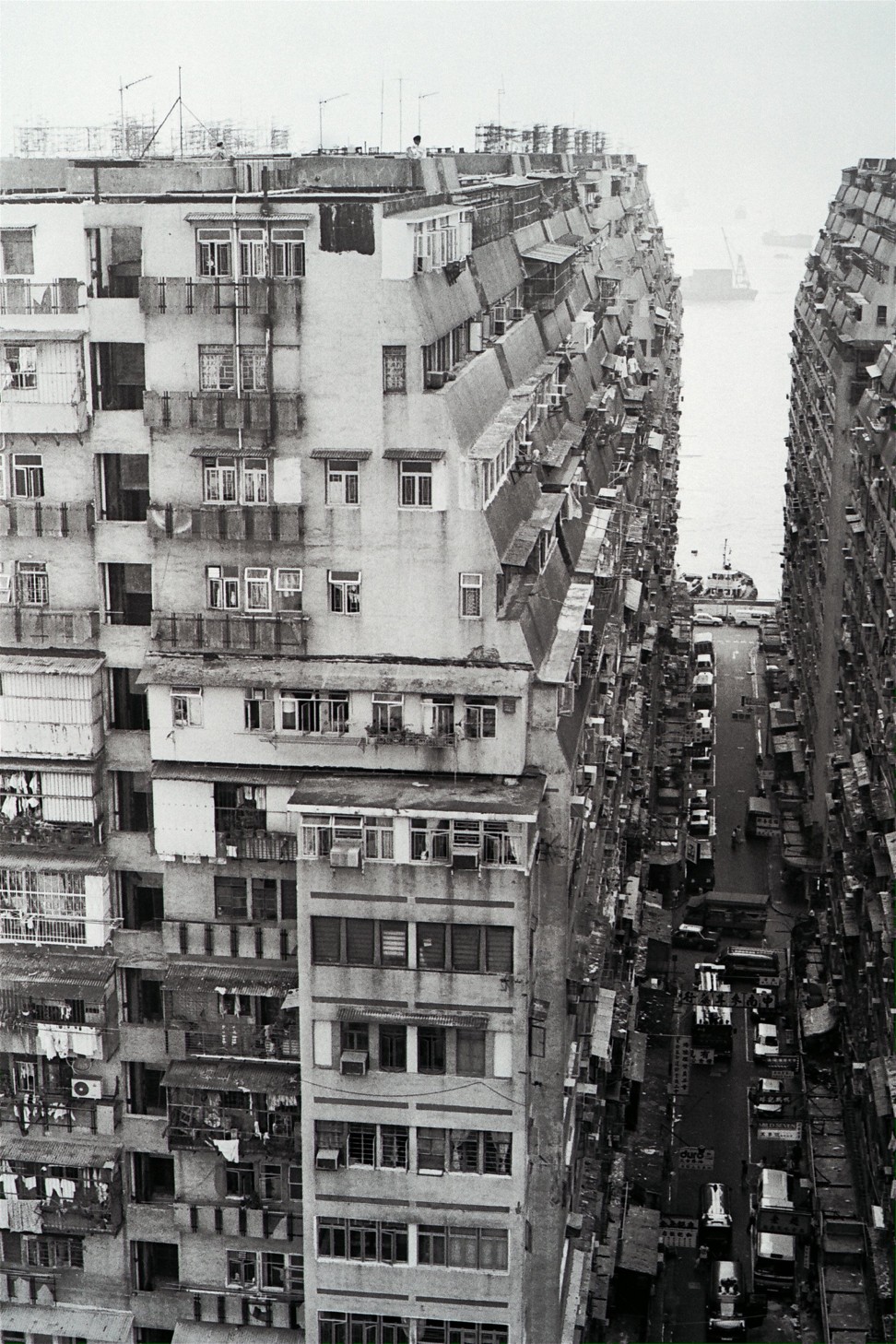

You can’t take anything for granted in Hong Kong. When Ferry Point was built in the 1960s, its eight large blocks projected out into Victoria Harbour like ocean liners. Today, they are landlocked, surrounded not by fishing boats and ferries but by cars, trucks and – when the new Express Rail terminus opens next year – high-speed trains.

Some might recognise the neighbourhood by its Chinese nickname, bat man lau: the Eight Man Buildings. That’s because the names of its buildings and streets all begin with the Cantonese “man”, which finds itself in a number of auspicious words such as culture, civilisation and language. When plans for the development were unveiled in 1961, it was initially called Man Wah Sun Chuen, and it was targeted at Hong Kong’s small but growing middle class.

“It was a very typical middle-class residential area like Mei Foo Sun Chuen, but not as high class, because of the location in Yau Ma Tei – it’s a grass-roots area,” recalls Christopher Leung, who was a teenager when his family bought a flat in the last of the neighbourhood’s buildings, which was completed in 1971.

On the surface, the development really did share a number of qualities with Mei Foo. Like that landmark project, Ferry Point’s initial wave of residents was upwardly mobile. Many owned cars, even though the buildings had no parking garages, so entrepreneurs operated valet parking services next to the Jordan Road Ferry Pier, which carried pedestrians and vehicles to Central. And like Mei Foo, Ferry Point was part of a new generation of housing estates built on former industrial sites; in this case, a cotton warehouse and gas depot.

But the similarities end there. Whereas Mei Foo’s groundbreaking architecture set the stage for a completely new style of high-rise development, Ferry Point marked the end of an older type of housing.

As the buildings grew, building regulations were changed to require setbacks, which gave a number of Ferry Point blocks a distinctive pyramid shape. Eventually, the limitations of composite buildings, and the success of Mei Foo, led to a complete overhaul of building codes, which encouraged a proliferation of the skinny towers that are common today.

As the last of its generation, Ferry Point aged quickly. “Some people say the buildings were built when water shortage was a problem,” says Leung. “There was not enough fresh water, so there was a rumour that the developers used saltwater to make the concrete.”

But it was still a big step up from the overcrowded tenements of Yau Ma Tei, and Ferry Point attracted many ambitious residents who would go on to achieve success, including doctors, lawyers, and future entertainment megastars such as Jackie Chan, Sammo Hung Kam-bo and Stephen Chow Sing-chi.

Its waterfront location gave it a certain cachet. Every June, dragon boat races took place in the adjacent typhoon shelter. On misty days, the wail of foghorns echoed through the streets.

Kwok, whose account was recorded by the Hong Kong Memory oral history project, says the neighbourhood began to attract a diverse crowd of residents. Many former Gurkhas and their families moved into the area around the handover in 1997. “It has become like the United Nations,” says Kwok. “You can always smell curry and coconut from the cooking.”

“They’ve all gone elsewhere, but people still come back and buy many sandwiches at a time,” he says. “Keep them in the fridge and put one in the oven when you want to eat it.”

Christopher Leung left the neighbourhood when he got married in 1978. He eventually moved to Brisbane in Australia, but he still returns to Ferry Point to visit his elderly parents, who live in the same flat they bought in 1971.

“Now I notice the age of the residents – there are more and more old people living in the area. And it’s getting more and more multicultural,” he says.

But the biggest change is the absence of the harbour. Land reclamation for the airport highway and railway moved the waterfront nearly 600 metres away in the 1990s. “I miss the sea,” says Leung. “In the old days, I would go downstairs, just a few steps and I was at the water. Now I can hardly see it.”