Stories behind Hong Kong districts: Tsuen Wan – from Hakka farms to textile mills to a post-industrial future

Shanghai industrialists transformed a rural district with textile factories that spawned shanty towns for their workers; new town status, MTR’s arrival and industry’s decline were cues for rapid residential and commercial development

“I know much of it is ugly.”

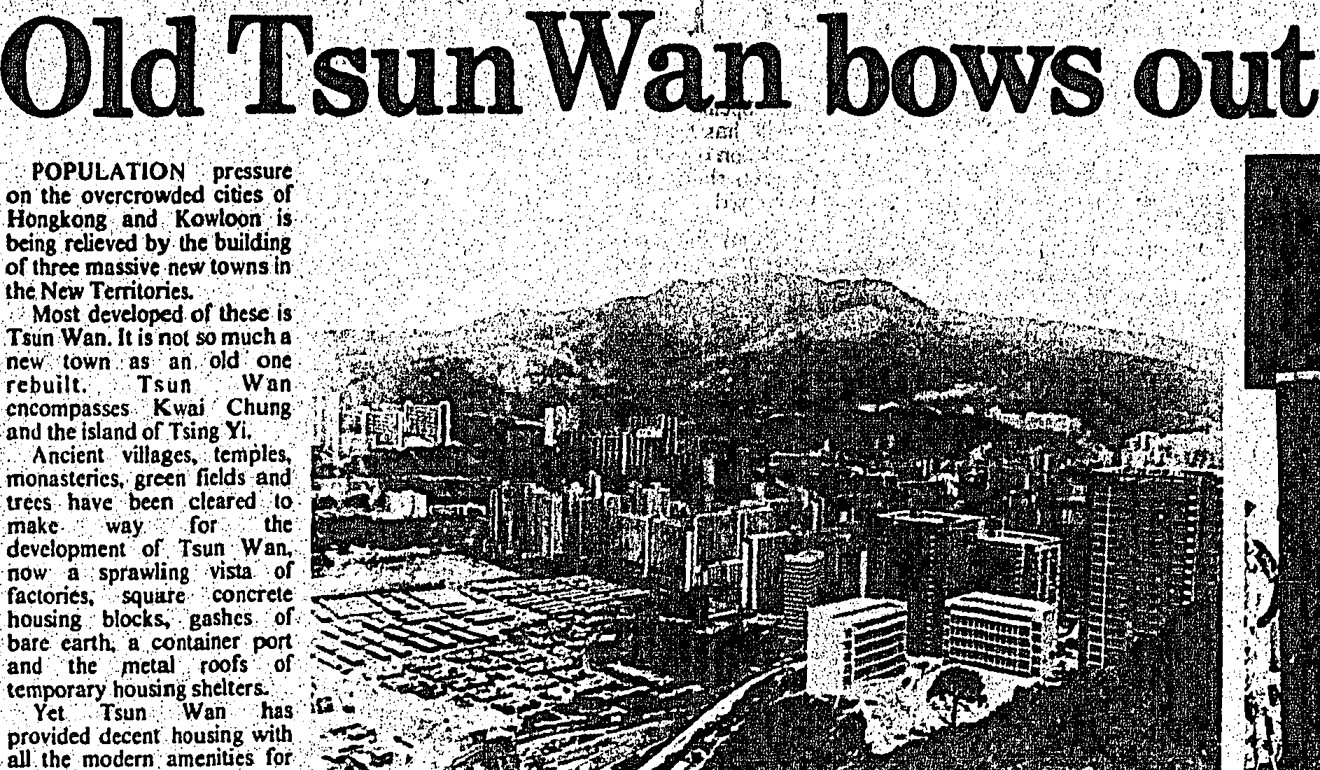

That was Jimmy Hayes, Tsuen Wan’s town manager, quoted in the July 20, 1977 edition of the South China Morning Post. They aren’t the words you might expect from a municipal leader, but they were truthful: the scene in 1970s Tsuen Wan wasn’t exactly postcard material.

Yet it was vital, thriving and important. Hong Kong’s economy was booming and textile factories were opening in Tsuen Wan faster than the government could build infrastructure. Thousands of workers wove silk, dyed cotton and assembled garments for export overseas.

When Hayes spoke to the Post in 1977, the district was home to 550,000 people, with plans for another half a million. Much of the population had been relocated to public housing estates from hillside shanty towns. Others lived in private estates that sprang up around the future Mass Transit Railway (now called simply MTR) station, whose construction was announced in 1975 and which was finally completed in 1982.

Live the history of Hong Kong, how it grew from colonial opium trading outpost to global finance mecca

“People tell me the development is depressing, but they are only seeing the present,” said Hayes. “We will build a fine city eventually.”

If Tsuen Wan encapsulated the rise of industrial Hong Kong, so too does it reflect Hong Kong’s metamorphosis into a service economy. From the cable-stayed span of the Ting Kau Bridge, you can see the soaring glass walls of Nina Tower, the sixth tallest building in Hong Kong, as well as the hulking shells of defunct textile mills. In between is a motley landscape of old tong lau (tenement buildings), towers of luxury flats, shopping malls and public housing estates.

Stories behind Hong Kong districts: Mei Foo Sun Chuen, where middle-class dreams began

“A lot of old shops and buildings remain, so it’s easier to get a sense of what Tsuen Wan was like in the past compared to other areas,” says Annette Lo Ngan-kee, who coordinates educational programmes for the MILL6 Foundation. MILL6 is part of The Mills, a project to transform the former Nan Fung cotton mill into a centre for art, fashion and design.

A lot of old shops and buildings remain, so it’s easier to get a sense of what Tsuen Wan was like in the past compared to other areas

On a recent sunny day, just after a spate of typhoons, Lo was showing some visitors around the heart of Tsuen Wan, where shops and wet market stalls spill into busy streets. After stopping at a 50-year-old calligraphy shop, the group made its way towards the Jockey Club Tak Wah Park, opened in 1989 on the site of Hoi Pa Village, an old settlement of the Hakka Chinese minority.

Just two structures from the village remain: the ancestral hall and a grey brick house built in 1904 by Yau Yuen-cheung, a scholar. Like much of Hong Kong, Hoi Pa was settled by Hakka migrants who arrived after the Qing dynasty rulers of China expelled all people from the coasts of Guangdong between 1661 and 1669, in an effort to weed out rebels loyal to the fallen Ming dynasty.

By the time the British leased the New Territories in 1898, about 3,000 people were living in villages around Tsuen Wan. They farmed pineapples, raised pigs and set up workshops that made incense and tofu skin. “Deer, wildcats and prowling tigers were common,” reported the Post.

Hong Kong’s last tiger was killed in 1915, and Castle Peak Road reached Tsuen Wan in 1917, but change was otherwise slow to come until 1949, when refugees from China flooded into Hong Kong. Among the more prosperous arrivals were industrialists from Shanghai, who moved their textile businesses to Tsuen Wan, taking advantage of port facilities along the Rambler Channel.

Stories behind Hong Kong districts: Pok Fu Lam Village, once a rural idyll, unbowed amid uncertain future

By 1961, 84,000 people lived in Tsuen Wan, more than two-thirds of them in houseboats, shanty towns and other forms of informal housing. That prompted the colonial government to designate Tsuen Wan a new town, and launch a master plan for its development into a self-contained satellite of Hong Kong.

The plan gave shanty dwellers safe, secure housing. But for indigenous villagers, it meant upheaval.

After leaving Tak Wah Park, Annette Lo stops in front of Shek Pik New Village, a complex of walk-up flat buildings erected to house villagers displaced by the Shek Pik Reservoir in 1957.

“It must have been an earth-shattering change for them,” she says. She points up at the village temple, housed in a top-floor flat. “It’s on the uppermost floor so nobody tramples on the gods.”

Many of those villagers would have found work in Tsuen Wan’s textile factories, but by the early 1980s the industry was already in decline. The February 1, 1982 edition of the Post announced a “gloomy future” for the textile industry, thanks to a global recession and Hong Kong’s changing economy.

Stories behind Hong Kong districts: SoHo before the escalator

Many factory owners sold their land to property developers, leaving workers in the lurch. Among those who suffered was the Ha family, three generations of which were thrown out of work when the Wyler textile mill closed in 1981. It was the first time the patriarch, 75-year-old Ha Chuen-leung, had been jobless in 60 years of textile work.

These days, Tsuen Wan’s textile industry has been almost entirely obliterated, but the impending launch of The Mills has led to a kind of resurgence. As the complex prepares to open next year, the MILL6 Foundation has been pairing former garment workers with young designers to help them exchange skills.

Making her way from Tsuen Wan’s old market district, past a man drying sea cucumbers outside the City Walk shopping centre, Lo reaches the Fuk Loi Estate, a cluster of mid-rise buildings that opened in 1963. This is where, for the past several months, MILL6 workers have installed a weaving machine every Wednesday.

“We set it up and engage anyone who happens to be here,” says Lo. It’s a way to expose youngsters to a part of Tsuen Wan’s history – and to gather stories from people who were themselves textile workers.

Fuk Loi may have been ugly when it first opened, but these days it is a slow-paced estate with small shops and neighbours who chat under big trees. Jimmy Hayes would approve.