Bali businesses struggle to convince tourists it's safe amid volcanic eruption

Tourist industry in holiday island's poorest district, in northeast, hit hardest by Mount Agung’s eruption, which has spewed ash kilometres into the air

Frantic shop owners in Bali have been trying to persuade tourists that they are still open for business, but volcano Mount Agung’s eruption tells another story.

“We are still open, we’re 18 kilometres away from the volcano. Another mountain protects us. The wind is not coming to Amed, and even if it did, the ash would not reach us,” says Nyoman Miskin Aryana.

Almost 19,000 mainland Chinese and Hong Kong visitors stranded in Bali as ash from Mount Agung keeps flights grounded

The Balinese man runs a three-bedroom guest house in Amed, a coastal village normally popular with scuba divers and travellers seeking a quiet getaway on the less developed northeastern shore of Bali. However, business has been slow, and it’s only to be expected. Mount Agung has spewed ash kilometres into the air, forcing the closure of the island’s international airport for almost three full days and stranding tens of thousands of tourists. The airport reopened late on Wednesday, but it was unclear whether all flights would resume. If wind conditions change it could be closed again.

As the volcano continues to hurl ash skywards and shows signs of an imminent bigger eruption, life in many parts of the island have been affected.

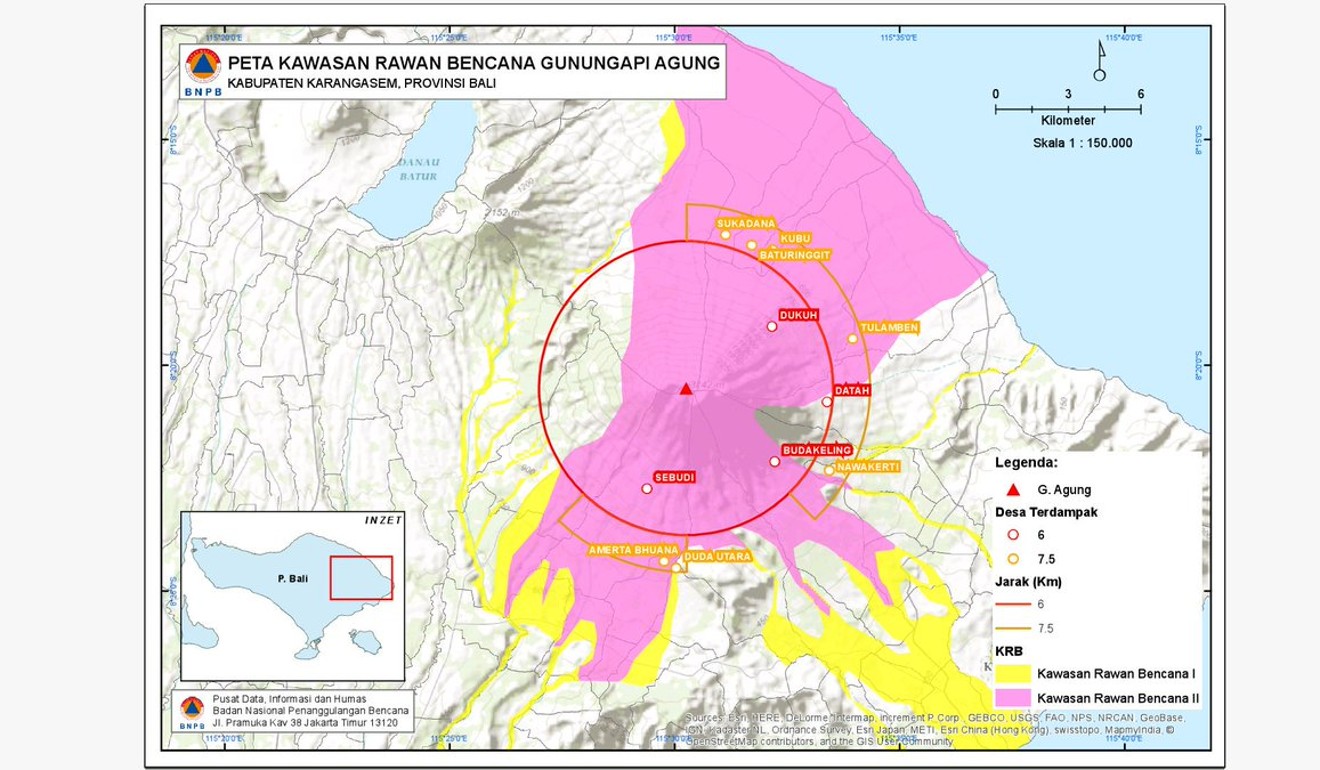

About 100,000 people who live within the “danger zone” of its slopes were ordered to evacuate.

Amed and most villages lining the coastline of Karangasem district are outside the official danger zone, but their inconvenient location, wedged between the mountain and the sea, means the area hasn’t seen anywhere near the usual number of visitors ever since Mount Agung started rumbling in September.

“The local residents, who run guest houses, restaurants, or scooter rentals, are struggling,” says Arnaud Billon, a Frenchman who manages Two Fish, a dive centre in Amed.

His dive school had been hosting a scuba instructor workshop in September, when “tremors all day long” began scaring people away. Mount Agung wasn’t yet erupting, but the heightened seismic activity led Indonesia’s regional disaster mitigation agency (BNPB) to raise the alert level and order the first wave of evacuations.

By the end of the workshop, Billon had to close the dive centre, and Amed started taking in refugees from the nearby mountain. Two Fish and other resorts then raised money to help refugees with food and water, says Billon.

Mount Agung’s eruption is in the lap of the gods for Bali’s Hindu population

The situation eased up momentarily in November, when BNPB lowered the alert level and some tourists returned, but it didn’t last long. Last week, the volcano began spewing ash. “A lot of people cancelled,” says Billon.

The people in Amed feel safe, even if Mount Agung doesn’t calm down any time soon. But they are frustrated by the lack of income. Many have built livelihoods that depend on tourism.

The dry and rocky Karangasem district is one of the poorest on the island, and ranks lowest out of all Balinese districts in the government’s human development index.

A receptionist at a guest house that partners with Two Fish says the problem isn’t safety, but access. “The ash will not reach us, but it’s difficult for guests to find transport to come out here. Drivers don’t dare to,” he says.

Billon had considered shuttling guests to Amed on his own, but decided against it because he was worried his insurance wouldn’t cover it if something did happen along the way.

Wayan, who goes by one name, is a local resident who operates tours and a small beachside restaurant called Green Papaya. He says it’s been “very tough. I’ve not had any customers for the past three days.” Amed residents also aren’t considered refugees, which means they don’t get government support or food aid.

Ida Bagus Ketut Arimbawa, head of the BNPB in Karangasem district, said that the priority for the agency has been to evacuate those residents in the immediate danger zone. He said there have been discussions about helping small businesses in the area by reducing the rate at which they have to repay bank loans, but that this would take time to assess.

“The people here live off what they have,” says the receptionist, who did not want to be named. “Some go back to fishing. Luckily it’s a good season for fishing. The market is still open as normal. It’s just that the tourists are more careful.”

Billon’s dive centre has multiple branches in Indonesia, some in more easily accessible and safe areas in Bali, some on other islands. He is been able to shift guests and staff to other locations, so the effect on his business hasn’t been as bad as for others.

‘Be ready to evacuate at short notice’: following months of anticipation, Bali’s Mount Agung erupts

Now Aryana isn’t sure whether the guests who have made reservations for his guest house, Chez Kin, will show up. “Last year, November and December were busy. I have two rooms booked now, let’s hope they’ll come,” he says.