Hue: what to see 50 years after Vietnam war’s Tet offensive nearly destroyed the historic city

City was badly damaged by fierce urban warfare that followed North Vietnamese Army’s surprise lunar new year attack in January 1968, but there’s still much to see of citadel from where emperors ruled for 150 years

Sipping warm ginger tea in the Truong Du pavilion and watching the soft rainfall on to the glassy surface of the ornate carp pond, it’s hard to imagine that fifty years ago, this tranquil part of Hue’s historic citadel was the scene of one of the most intense and bloody battles of the Vietnam war.

The pavilion is part of the splendid Dien Tho Palace, once the exclusive preserve of the imperial queen mother, where she would take the air and exchange court gossip with her coterie of loyal ladies-in- waiting. It’s part of the Imperial City in Vietnam’s former capital, designated a Unesco World Heritage Site in 1993.

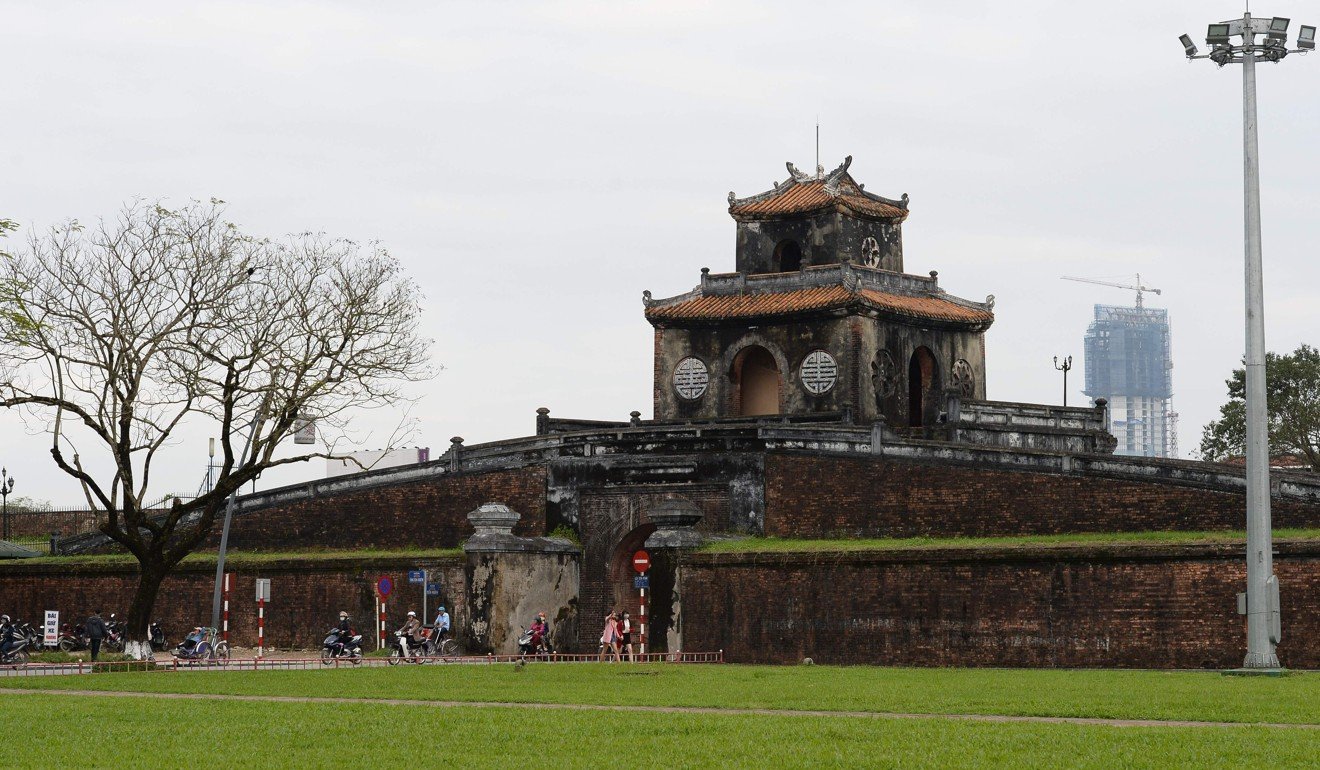

Fashioned after Beijing’s Forbidden City, the Imperial City stands within the walled confines of the imposing red stone citadel, which encloses an area of some 520 hectares. It stands along the picturesque northwestern bank of the Perfume River. The Imperial City is protected by its own walls measuring 2km by 2km and the complex includes impeccably restored gate houses, temples, tombs, pavilions and moats.

Construction started on the orders of Emperor Gia Long in 1804 and it was to be home for 13 rulers of the Nguyen dynasty until 1945 when, within the grounds of the palace, the last emperor of Vietnam relinquished his throne.

Playboy, bon vivant and the last emperor of Vietnam, Bao Dai chafed at his role as France’s puppet

The so-called playboy emperor, Bao Dai, dismissed by many as an obliging puppet of the French imperialists, surrendered his ceremonial sword to the charismatic revolutionary and nationalist Ho Chi Minh.

These days it’s a popular visitor destination, and the distant, sonorous striking of a gong is often the only sound to be heard across the site of the Imperial City, where each building was carefully placed according to the advice of trusted royal geomancers.

This month marks the 50th anniversary of the outbreak of the Battle of Hue, when, in the early hours of 31 January 1968, the walls of the old citadel echoed to the sound of rocket propelled grenades and machine gun fire. The People’s Army of Vietnam (NVA) supported by Viet Cong (VC) guerillas, launched an audacious attack on the city as part of the Tet offensive against multiple targets in southern Vietnam, so called because it began at Tet – lunar new year in Vietnam.

Book review: the bloodiest Vietnam war battle, Hue, 1968 – a searing account of courage and cowardice

“Hue was one of the fiercest battles of the Vietnam war, both in terms of its human cost as well as the amount of physical destruction it generated,” says Erik Villard of the US Army Centre of Military History, who specialises in the Vietnam war.

The citadel of Hue, widely regarded as the cultural capital of Vietnam, became the key battleground in 25 days of urban warfare which raged within its walls, gardens and moats.

According to Villard, 216 US servicemen and 421 South Vietnamese troops were killed in the action, and some 1,600 US soldiers and 2,100 South Vietnamese wounded. North Vietnamese losses were estimated at 2,500 to 5,000.

The battle also claimed the lives of some 4,000 innocent civilians, many the victims of bitter sectarian reprisals.

When the thousands of Vietnamese living within the citadel awoke on January 31, 1968, they saw the North Vietnamese liberation flag flying from the flagstaff tower (Cot Co), a huge rectangular red stone block on the southern walls of the city. The flying of the flag was designed to provoke a popular uprising against the country’s foreign oppressors.

A giant modern red and gold Vietnamese version now flies from the tower, which still dominates the city skyline.

The most pleasant way to access the citadel is to take one of the many boats offered for charter on the southern bank of the Perfume River, where most of Hue’s tourist hotels are. The boats take visitors on a cruise upstream to view the opulent pavilions and gardens of the Nguyen imperial tombs along the banks of the river.

Hue was one of the fiercest battles of the Vietnam war, both in terms of its human cost as well as the amount of physical destruction it generated

If business is quiet, they will transport passengers the 200 metres or so across the river to the foot of the flagstaff tower. From there it is an easy stroll to the southeastern gate of the citadel (take care to dodge the interminable stream of motorbikes). Proceed past the 19th century brass ceremonial nine- deities cannons, to the royal south gate (Ngo Mon Gate).

Here, for a modest fee you can enter the confines of the Purple Forbidden City at the Imperial City’s centre, where the imperial family lived for 141 years.

Fifty years ago, this picturesque area where today tourists snap selfies was the scene of intense bombardment; many of the walls and gatehouses have been reduced to little more than rubble. As US and South Vietnamese forces sought to penetrate the citadel and evict the insurgents, efforts were made to restrict the degree of damage inflicted on the Imperial Palace.

“US forces used artillery, naval gunfire and an occasional air strike to suppress the enemy on the outer wall, but could do nothing about the snipers in the Imperial Palace because the royal residence was a no-fire zone,” says Villard.

Later, as South Vietnamese and US forces clawed their way back into the city and forced the insurgents back, the NVA forces made their last stand in the imperial palace grounds and in the citadel’s southwest corner. Ultimately, military victory became a greater priority than preserving Hue’s cultural heritage.

Where to get an up-close look at Vietnam’s long history of war

“The battle of Hue damaged or destroyed about 80 per cent of the buildings in Hue and temporarily displaced around 100,000 people,” says Villard. “Many hundreds of corpses remained unburied in the shattered buildings.”

Despite decades of reconstruction work, there are still traces of the battle. Apart from the bullet holes still visible in parts of the city wall, the most obvious reminder is a motley collection of military relics at the Historic and Revolutionary Museum near the east gate. Exhibits include an M48 Patton battle tank and a US Navy A-37 Dragonfly light attack aircraft.

“Allied forces finally swept the last NVA troops from the city and restored the SVN [South Vietnamese] flag to the main tower on 24 February, 1968,” says Villard.

Behind enemy lines: Vietnam’s female spies who helped change the course of the war

The palace was populated by royals with their attendant ladies-in-waiting, concubines, servants, mandarins, courtiers and eunuchs. It is said that when Emperor Tu Duc died in 1883, his 103 concubines were forced to live next to his tomb for two years of mourning before they could return to the Imperial City.

Of the five gates built into the citadel’s 15-metre-high granite walls that allow access to the Imperial City, the central one was reserved for the emperor. The Five Phoenix Watchtower, its red and green tiled roof adorned with elaborate dragons and flowers, rises some 20 metres above it.

Cross the moat on the golden water bridge to the impeccably restored Palace of Imperial Harmony (Thai Hoa) decorated with enamelled bronze ware, gilding and lacquer. This is where the imperial business of state was undertaken.

Beyond it is the third enclosure of the Purple Forbidden City, much of which was destroyed in 1968; there is an open grass area among which stand buildings in various states of disrepair.

Stone covered walkways surround the final enclosure and it’s a pleasant place to wander, pondering the story of the 13 ill-fated Nguyen emperors.

They made peace with China after two centuries of domination, were exploited by the French colonialists, exiled by the communists and then saw their nation devastated by what Vietnamese call the American war.

Thanks to the efforts of conservationists, 50 years after the Battle of Hue, their story can be revisited and the walled city is enjoying a renaissance as one of Southeast Asia’s most important cultural heritage sites.

Sweeping new history of the cold war a reminder of how stupidity, ignorance and arrogance almost brought the world to annihilation

Getting there: Cathay Pacific, Cathay Dragon and Hong Kong Express all offer 80-minute direct flights between Hong Kong and the international airport at Da Nang, some 100km to the south of Hue. The city can be reached by bus or car from Da Nang, but take the slightly dilapidated Reunification Express train from Da Nang station to Hue for some wonderful views along its winding coastal route.