Where do Bali’s least popular tourists come from? Indonesian locals have a reputation that is hard to shake

It is hard being an Indonesian visitor on the Indonesian tourist island of Bali, where motorcycle rental businesses will tell you there are no rides left (there are) and restaurants will say they are full (but let in groups of foreigners)

Putu Sudiwiadnya smiles when asked where most of the customers of his motorcycle rental business come from. “Nearly 100 per cent are foreigners,” he says.

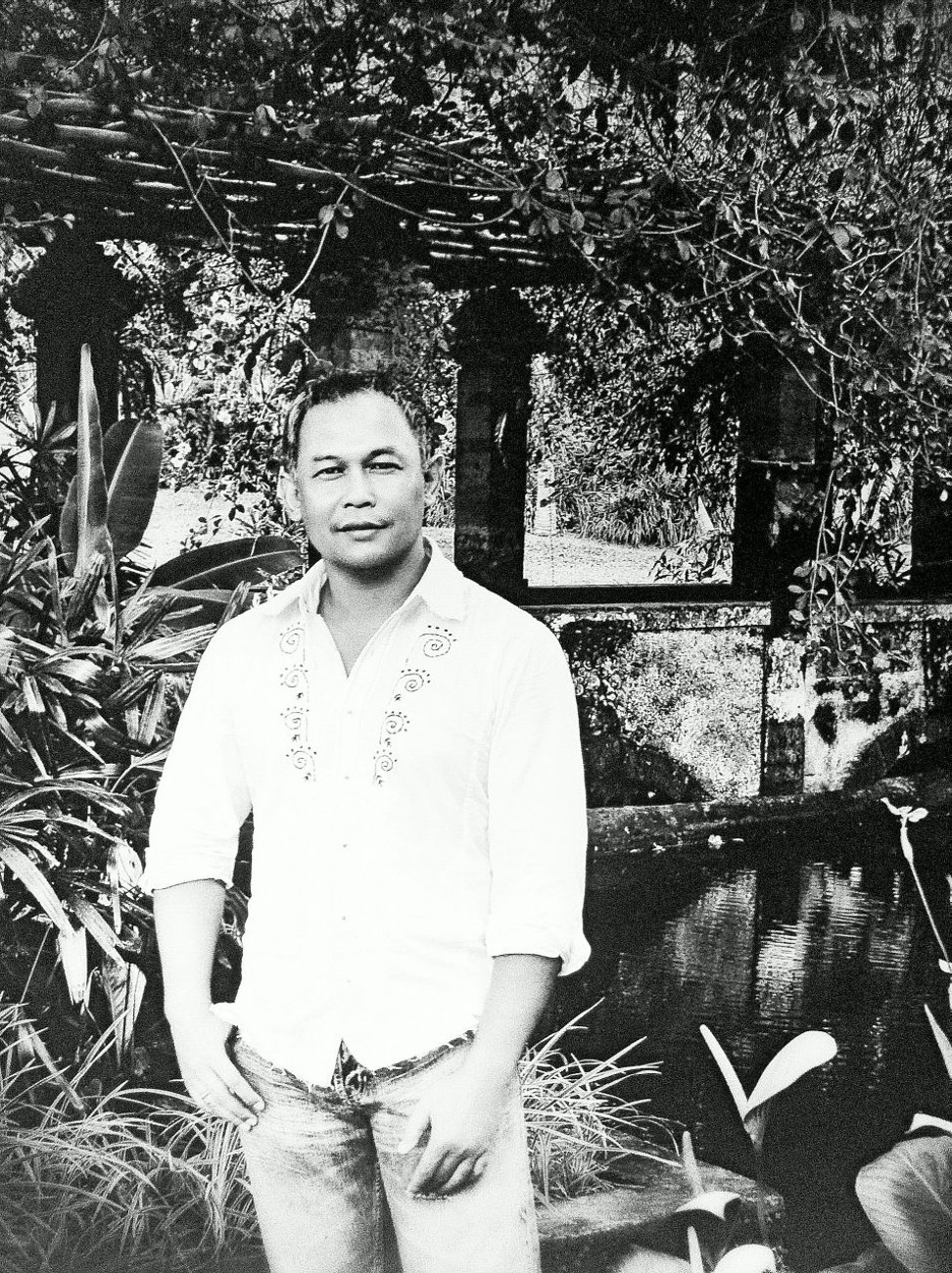

Putu opened his business in Ubud, on the Indonesian tourist island of Bali, in 2001. The jolly 40-year-old says the town, Bali’s cultural heart, was a relatively sleepy one at the time, but now attracts millions of tourists a year.

How Indonesia’s intrepid sulphur miners became a tourist attraction

Indonesia welcomed about 14 million foreign visitors in 2017, with some 40 per cent travelling to Bali, according to official statistics. The island also attracts roughly the same number of holidaymakers from other parts of Indonesia. But Putu would rather rent to visitors from any country other than his own.

“I’m not the only one,” he says. “When local tourists ask, we tell them that all the bikes are rented out.”

Putu’s candidness may come as a surprise, but Indonesian tourists visiting Bali have long griped about preferential treatment given to foreign holidaymakers.

Ndari Utoyo, a senior vice-president of operations at a technology company based in Jakarta, had a similar experience when he was refused entry to a club at a resort village in Bali.

Bali’s luxury real estate profits from tourism and investment growth

“I was going to this famous lounge in Canggu. They stopped me right at the door and told me that I couldn’t go in because I didn’t have a prior reservation,” Ndari, 33, says.

“Before I could tell them that I wouldn’t mind being put on a waiting list, some foreign tourists walked past us without being asked anything, and they were shown to a table right away.”

Ndari’s experience is hardly unique. Domestic tourists travelling to Bali have shared stories about being denied service or having difficulty making reservations, just for “looking local”. Some turn to social media to air their grievances; others share their experiences on review sites and blogs.

One reviewer turned to TripAdvisor to describe a similar experience to that of Ndari when visiting a restaurant and bar with three friends and being turned away at the door.

“The reason they said is FULL but is not! as the other foreigners/expatriates group, couple or solo guest are allowed to enter. Local group were not allowed to enter,” the reviewer wrote.

Another reviewer, with a Western name, had a different experience, writing: “Did not want to leave, wanted to stay longer! Great for drinks, absolutely not to miss! Good music and crowd. Hidden Gem.”

I do feel sorry whenever I turn away customers, but it’s a decision I have to make. When my motorbikes were lost … I was left without a source of income for days

Yet the reason foreign tourists seem to be more welcome by locals in Bali seems to be more than just skin-deep.

For Putu, it comes down to experience. He says he only decided not to rent to locals three years ago after a series of incidents left him out of pocket.

“My motorbikes were stolen numerous times, always by locals who approached me as ‘tourists’. One time, one of the bikes was smuggled to Java. Another time, somebody went and pawned the parts,” he says.

“I run a small business here. As with any business, you try to accept that there are risks. I do feel sorry whenever I turn away customers, but it’s a decision I have to make. When my motorbikes were lost, not only did I have to pay millions of rupiah to replace them, but I was also left without a source of income for days, sometimes weeks.”

Putu admits that there was one instance in his 17 years in the business when a foreign tourist ran away with one of his motorbikes, but adds that he later found out he was suffering from mental illness.

He insists he is not being discriminatory. “I know that I’m making some generalisations, but the rental business is about trust. I need to know that I can trust my customers before I hand over the keys,” he says.

Anak Agung Gde Ariawan, who also goes by the nickname Odeck, is a well-known cultural observer of Bali and owns several businesses on the island. The non-Balinese native says that when tourism took off on the island in the 1970s, many Balinese suddenly found themselves accommodating the needs and expectations of visitors from various social and cultural backgrounds.

“Japanese tourists behaved differently compared to the Europeans. So did the Americans. People have different expectations and it can get overwhelming. How do you make sure that you can perform your job well and keep all your guests satisfied?” he asks.

Decades ago, we didn’t have selfie-stick-wielding tourists or Instagram snappers, or migrants from other islands … People will always profile others. This is not exclusive to Bali

It was not easy, Odeck says, because Balinese culture had been shielded from the outside world and very few locals had travelled off the island. Balinese society is notoriously tight-knit, and collective participation is expected in almost every aspect of life. That means the islanders rely on each other for information and this often becomes collective knowledge, Odeck says.

“So the Balinese began sharing information with one another about the perceived traits of their visitors, unwittingly putting them in boxes. It’s learned, and over time it’s been translated into stereotypes.”

What a flood of extra tourists means for Indonesia’s Komodo dragon

Odeck has a theory on why the Balinese are wary of other Indonesian visitors. He says the first wave of Indonesian tourists during the ’70s and ’80s typically fitted into three different categories: government officials, airline professionals, and the ultra-rich from Java. According to Odeck, the enduring perceptions that the Balinese have toward domestic tourists probably stems from that period.

“Indonesia was still a very feudalistic society back then, and very few could afford to travel. The ultra-rich, who usually had many servants in their homes, came to a tourism establishment and often couldn’t understand the concept that hotel workers – such as housekeeping staff – had specific job assignments to them at the hotel. This misconception often resulted in them treating the staff like their own servants back home, possibly creating resentment.

“In comparison, tourists coming from developed countries tended to have travelled more, so such misunderstandings with staff rarely occurred. That’s how some patrons were preferred over the others at that time.”

Nowadays, more Indonesians are travelling. With this has come a new breed of visitors – and new stereotypes not confined to race. “Decades ago, we didn’t have selfie-stick-wielding tourists or Instagram snappers, or migrants from other islands,” Odeck says. “I think, to some extent, people will always profile others. This is not exclusive to Bali.”

He says he may have been racially profiled when he recently tried to make a reservation at a famous restaurant in the Australian city of Sydney.

“The first time I called, I didn’t get it. Then a friend told me that I should mention that I own some resorts in Bali. I called again and right away they accepted my reservation. This happens a lot in the [restaurant] industry.”

Sometimes, local tourists contact me via Facebook, which gives me an opportunity to chat with them first, so I can know if I can trust that person or not

Odeck also has his own experience of being stereotyped as a non-Balinese Indonesian on Bali. “Once, I went to a boutique hotel. When I tried to enter, the security guard stopped me and indicated the place where the drivers gather while waiting for their clients. He thought I was a driver.”

He says he was not offended and did not take it personally. “Of course, we can try to find the reasons as to why stereotyping happens in the industry. I don’t condone it, and I don’t think it’s right. But the way I see it, we can also learn to choose our own battles. Sometimes the stereotyping happens because of a lack of education, or a certain limitation in understanding how the world works. It is not ill-intentioned. They are just trying to do their jobs.”

In Ubud, Putu echoes this point. He argues that when he chooses whether to rent a bike to a certain customer, it is not racially motivated.

“Like I said, I’m just trying to manage the risks. When locals approach me they want to rent a motorbike right away. But I don’t know them. And from my past experiences, I don’t know if I can trust them or not.”

Active Bali volcano no deterrent to deadly cockfighting matches in Mount Agung’s shadow

Putu says he has his own vetting system.

“Sometimes, local tourists contact me via Facebook, which gives me an opportunity to chat with them first, so I can know if I can trust that person or not. I will then arrange to meet them first so I can decide whether or not to lend them a motorbike. A conversation first, then business transaction next. What’s wrong with that?”