Chinese Indonesians work to preserve 700 years of history in Lasem, a ‘Little China’ in Central Java

There was already a thriving Chinese community in Lasem when a captain of Chinese Admiral Zheng He arrived in 1413, and families still own homes built generations ago. As the young move away, preserving them becomes an urgent task

Frida Listiyani has remained in the house she shared with her husband, a ninth-generation Chinese Indonesian, since he died at the age of 74 a few years ago. She still prays for him and his ancestors at the altar in the home.

On every first and 15th day of each lunar month, she presents an offering of oranges to the Kitchen God. On the veranda hang portraits of her husband’s forebears, including his great-grandparents. She’s not sure which part of China they came from, but Frida – also known by her Chinese name, Tan Bwan Nio – says the house in Lasem, Central Java, remains more or less structurally unchanged since it was built by the first generation of her late husband’s family.

Lasem, a subdistrict about three hours’ drive from Semarang, the provincial capital of Central Java, was one of the earliest Chinese settlements on Java, Indonesia’s most populous island, and the many old homes and temples there serve as a reminder of its history.

Volume two of Chinese Epigraphic Materials in Indonesia, edited by the late German sinologist Wolfgang Franke and published in 1997, notes that: “The traveller who visits Lasem is struck by the fact that its centre still looks like a small traditional Chinese city [in] southern Fujian, hence its Malay name of Tiongkok Kecil, or ‘Little China’.”

The book notes that “The Peranakan, or local-born Chinese, of Lasem are known for the kind of language they speak, which is Javanese with an unusually large number of Hokkien terms.” Hokkien is a Chinese dialect widely spoken in Fujian province.

Afnantio Soesantio – born Tio Sian Gwan – says his great-grandfather arrived in Lasem from Xiamen, a city in Fujian, in the 1800s. A seventh-generation Chinese-Indonesian, he stays connected with his roots by following his ancestors’ traditional rituals.

The Lasem native still observes Cheng Beng (Ching Ming festival), Gui Jie (Hungry Ghosts festival), and Tiong Jiu Pia (Mid-Autumn festival), when he places rissoles and cake – snacks his ancestors used to enjoy – on the ancestral altar in his home.

The day my Chinese dad was declared a ‘bona fide’ Indonesian and given a new name

Chinese traders were making the journey to the strategic port on Java’s northern coast as early as the mid-14th century and easily acculturated. Documentary evidence shows that in 1351 there were two distinct areas of present-day Lasem – an administrative zone and a predominantly Chinese settlement where the commercial activity took place.

The early Chinese traders in the area acquired rice for export back to China, while they brought with them clothing and textiles in exchange. Many of the Chinese became permanent settlers, remaining as traders or acquiring land and becoming farmers.

In 1413, Bi Nang Un, one of Muslim Chinese Admiral Zheng He’s captains, voyaged to the area to spread Islam among the Chinese population, who practised Confucianism. The administration in what was then part of the Majapahit empire welcomed Bi and permitted the Chinese to establish a new village in what is now southern Lasem, and the population grew.

Agni Malagina, from the faculty of humanities at the University of Indonesia, explored Lasem’s Chinese cemeteries, and discovered that the early visitors to Lasem came from much farther afield in China than just the southern provinces, as had been commonly assumed.

On the graves’ headstones, Agni found the names of a number of villages from as far north as Anhui, Henan, Hunan, Shanxi, and Shandong. (The oldest headstone she found was dated 1768.)

“Evidently, [the villages] were not only in Fujian and Guangdong,” Agni says, referring to the two provinces from which most Chinese Indonesians originate. “It has already been mentioned in books that apparently there were those from other regions, but it wasn’t mentioned which provinces were they from – in the north of China.”

We must be aware that at some point there will be no one to continue the traditions. Then it will be just a story

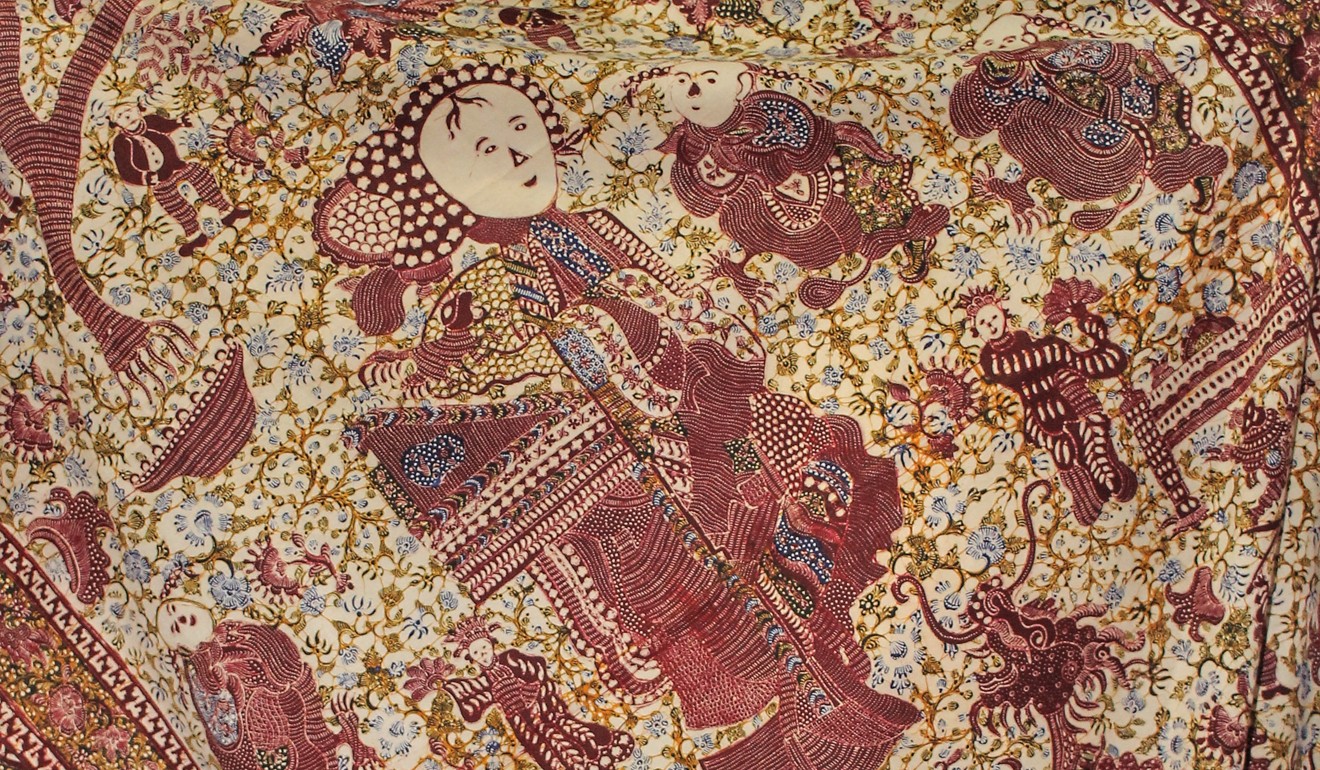

Priscilla Renny is a fifth-generation Lasem batik maker who runs the family business Batik Tulis Maranatha (Maranatha Handmade Batik). Her Chinese surname, in the Hokkien dialect, is Ong. She produces handmade Lasem batik textiles and clothing that is a distinct blend of Chinese and Javanese styles.

Renny says the Lasem batik motifs and dyeing techniques date back generations and maintain a cross-cultural uniqueness. According to some historical accounts, it was Captain Bi’s wife who pioneered the Lasem batik style, traditionally characterised by the predominant use of a blood-red colouring agent.

One of the batiks made by Renny features the motif of a young Chinese girl, symbolising long life, and is complemented by traditional Javanese patterns. Other Chinese motifs include dragons and flowers.

Renny’s work is highly valued because of the complexity of the patterns she creates, and a piece of her batik cloth sells for between 4 million and 25 million Indonesian rupiah (US$280 and US$1,770) depending on the size. She and her 30 co-workers produce at least 80 batik pieces a month, she says.

“I will keep safeguarding the preservation of Lasem batik, while also trying to make it popular with the younger generation,” Renny says.

Baskoro Pop, a member of the Discover Lasem community that promotes heritage preservation and utilisation in Lasem, says there is growing awareness of the need to preserve Lasem’s history. A few years ago, some residents suggested Lasem apply for Unesco World Heritage status. Baskoro sees signs of hope that Lasem’s heritage can be preserved.

How Bali’s Chinese were accepted and integrated into island society – in contrast to other parts of Indonesia

“The spirit of preservation is one of collective awareness,” says Baskoro, who has been guiding tours of Lasem since 2012. “Preservation activities have been going on in Lasem for a long time, but it is being done unconsciously.”

When a house is left empty following the death of its occupant, the younger generation who have moved to cities in search of better opportunities may still be reluctant to abandon the ancestral home. In such cases an older woman is often employed as a housekeeper to take care of the property. She is therefore playing a role in the house’s preservation, and such situations have become common in Lasem, Baskoro says.

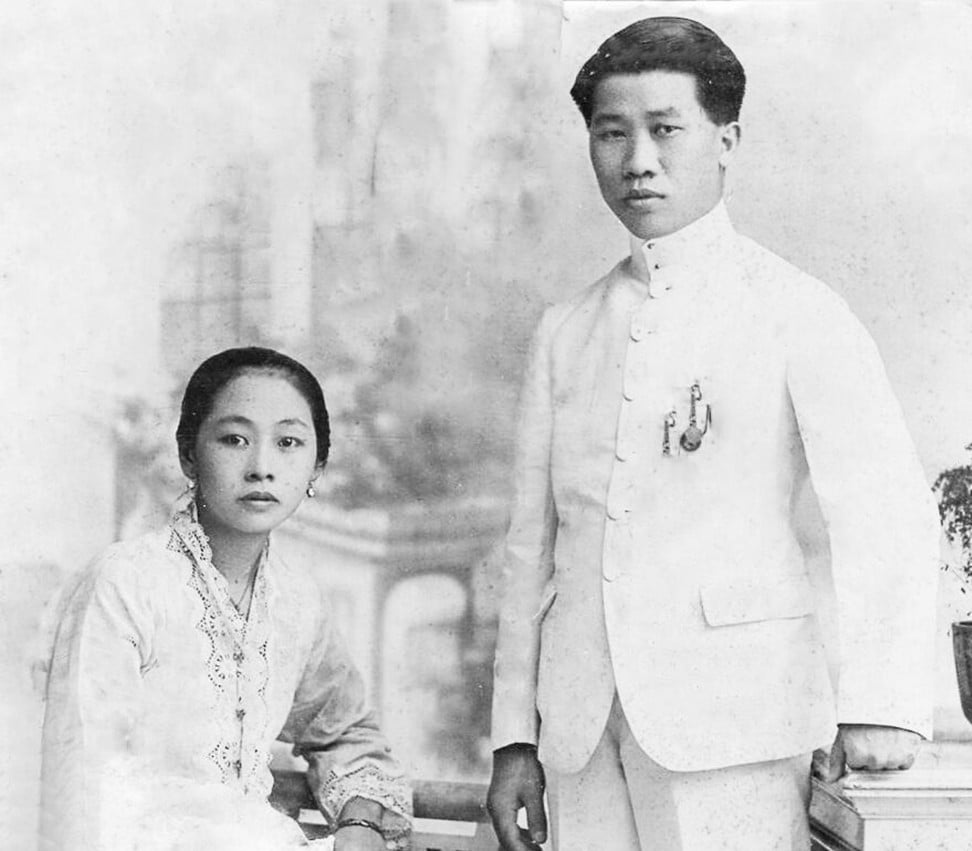

Like Renny, not everyone wants to leave the old home behind. Grace W. Susanto – a seventh-generation Chinese Indonesian also known as Oei Lee Giok – wants to preserve her family home, Roemah Oei (Oei House), as a heritage site. The original owner, Oei Am, was born in China in 1798 and arrived in Lasem at the age of 15. He later married a local woman.

Built in 1818, the house had been left in the hands of housekeepers for many decades before Susanto inherited it from her mother around the turn of the millennium. She says Oei Am probably has about 500 direct descendants, though many have left Indonesia for Hong Kong, Australia, the United States and Europe.

“We’re trying to preserve the house without changing it too much … Including the floor tiles you see, which are 200 years old,” she explains, adding that almost all the doors and window frames have been left in their original state.

Bangkok’s Chinatown braces for gentrification now subway station is about to open

Although there have been returnees – who come back to care for their ageing parents or take over the family business – there are still fears that Lasem’s Chinese culture could be lost.

Agni says there are very few of the younger generation of Chinese Indonesians from the old Lasem families left in the area.

“So we must be aware that at some point there will be no one to continue the traditions. Then it will be just a story,” Agni says. “The temple might be just a memory, a place to display statues of the gods.”

For now, at least, parts of old Lasem are being well preserved thanks to the efforts of conservationists and the Chinese traditions that are still observed. For example, during the most recent Chinese New Year celebrations in February, Lasem was crowded.

At the same time, Agni understands that Chinese culture in Lasem could be on its last legs because keeping old traditions alive is a challenge for all cultures.

“I think the people themselves have to grapple with the preservation of their traditions and customs,” Agni says. “We must remain steadfast in following our traditions as diligently as possible. That’s just how it is. You have to make it happen.”

Getting there

Cathay Pacific and Garuda Indonesia fly between Hong Kong and Jakarta daily. From Jakarta, several Indonesian airlines fly to Semarang’s Ahmad Yani International Airport, from where a private car can be hired for about 700,000 rupiah one way.