Before the US-China trade war: how America wooed the Qing dynasty with ginseng and furs

- An exhibition at the Hong Kong Maritime Museum explores the first century of trade between the US and China

- It illustrates how the problem of trade deficits is nothing new

Amid the tumultuous trade war engulfing China and the United States, a major new exhibition at the Hong Kong Maritime Museum steps back from the brink to explore the distant origins of trade between the two economic giants.

The exhibition, which runs until mid-April, illustrates how the thorny issue of trade imbalances is nothing new.

Whose economy is in the stronger state to survive the trade war?

“The China-US trade is a highly sensitive issue at the moment, but as a museum we can only reveal the story of the earliest days of this important trading relationship, and the many benefits it produced. Others are free to draw their own conclusions,” says museum director Richard Wesley of “The Dragon and the Eagle: American Traders in China, A Century of Trade from 1784 to 1900” exhibition.

The exhibition of some 250 objects has been some four years in the making, and includes rare artefacts and documents loaned from prestigious museums and archives in the US, including the Baker Library at Harvard Business School, the Peabody Essex Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

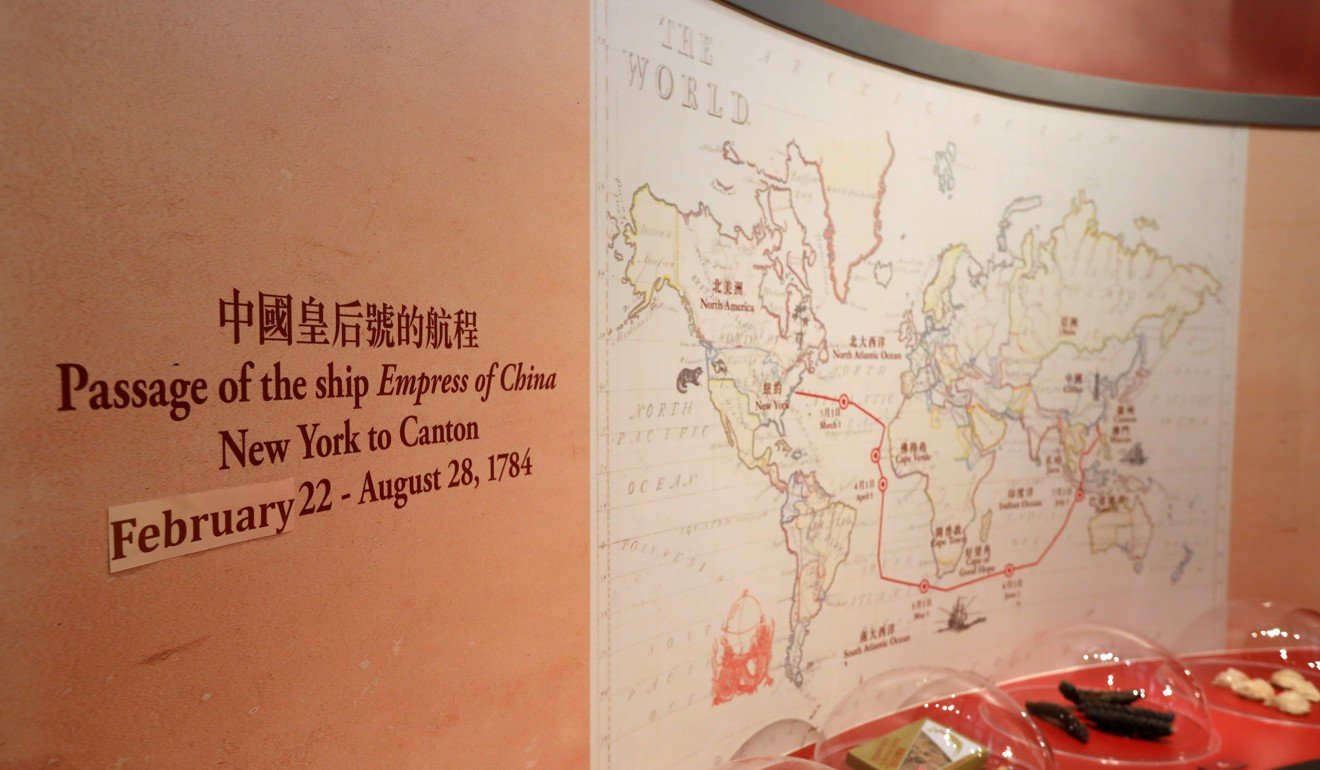

Together, the objects piece together the origins of a partnership that began on February 22, 1784 when a small sailing ship called the Empress of China sailed from New York harbour bound for the southern Chinese city of Guangzhou – then known as Canton.

In 2017, US trade with China was estimated at US$710.4 billion, but 234 years ago, as ship captain John Green – a burly Irish veteran of the American war of independence – packed his sea chest, China-US trade did not even exist.

Green’s mahogany and brass trunk is one of the exhibits, as is the original letter from the US Congress, dated January 13, 1784, commissioning the voyage that would take Green and his crew on a six-month, 18,000-mile (29,000-kilometre) journey on a ship about the same size as a Hong Kong Star Ferry.

It was both a private sector venture and an official mission, and it held the commercial hopes of the world’s newest nation, about to engage in trade for the first time, with one of the world’s oldest.

The exhibition reveals that then, as now, China-US trading wasn’t always smooth sailing, and an acute trade imbalance created tensions from the outset. Quite simply, China was largely self-sufficient and desired only silver in return for its coveted tea, silk and ceramics – and the imbalance was straining American finances.

America’s first generation of global capitalists proved to be highly inventive, and had a distinctive way of doing business. They were popular and trusted by the hong merchants of Canton, which was the only port open to international trade in Qing dynasty China.

“The US approach to trade was more collaborative and innovative, and that is how they are portrayed by the early Chinese hong merchants,” says Libby Chan Lai-pik, assistant museum director and curator.

The young nation was seeking new markets, was desperate to obtain tea (already the drink of choice in 18th century America) and urgently needed to repair an economy ravaged by the war of independence against Britain, Chan explains.

I am not an economist or a diplomat but, as a historian I think there might be lessons to be learned from those early days of trade.

Rather than adopt the heavy-handed tactics of the colonial British, the Americans had researched the market carefully to ascertain what China needed, and were prepared to be innovative.

“They traded with native Americans to source ginseng, and recruited leading botanists to develop attractive plants and pursue drying techniques, so the plants would not rot while en route to China,” says Chan.

The first two decades of the 19th century were the peak period for the American ginseng trade, when more than a third of all ginseng imports to China came from the US, says Chan. An original bill of lading document for the medicinal root is on display at the exhibition.

The Americans also sourced seal and otter fur, sandalwood from Hawaii, and harvested sea cucumbers. They used smaller, faster vessels than those of their European competitors, and they were generally more flexible, too.

When the Chinese first met the crew and merchants of the Empress of China, they called their visitors, the “new people” or “flowery flag people”, referring to the stars on the American flag. They regarded the Americans as less hierarchical and fairer to deal with than the British. They were also willing to comply with local regulations.

“The Americans wanted to build a relationship built on mutual benefits,” says Chan.

It’s a theme some analysts think characterises the modern trading relationship between the two nations.

“I am a trade policy expert, not an economic historian. So my historical focus tends to be on the last few decades not the last 200 years, but notwithstanding the recent friction and tensions, this has been an overwhelmingly beneficial relationship for both sides,” says Stephen Olson, research fellow at the Hinrich Foundation.

The reason why the US-China trade talks will work: it’s the personal touch

The foundation, which advocates mutually beneficial and sustainable global trade, is a key sponsor of the exhibition. It hosted a seminar at the museum to coincide with the exhibition opening, on the past, present and future of China-US trade, featuring prominent speakers, including US Consul General for Hong Kong and Macau Kurt Tong.

“This is one of, if not the most, important issue in the global trading system – the two largest economies and two largest trading powers need stability built into their relationship,” Olson says.

He concedes that not all of China-US trade has been positive or sustainable, but believes the mutual benefits have been significant in terms of development, growth and as an important contributor to global engagement.

“The challenges today are about two fundamentally different economic systems – the free-market USA and the state-directed capitalism in China – but there is still a way to find accommodation between these two systems. We should be able to make this work,” he says.

Profound differences were evident from the start of the China-US commercial relationship, but the two sides managed to make it work.

In 1784, America was a young and ambitious trading nation, while China was a vast, ancient and mostly introspective empire influenced by Confucian philosophy, which attached little value to commerce or trade.

Despite the huge gulf in language, culture, history and values, trade prospered and long-lasting friendships were made. Relationships were built in the most unlikely of circumstances, between the men in neckties and white-powdered wigs, and those dressed in elaborate silk robes sporting Manchurian hairstyles.

Then & now: the Canton spirit

The chairman of the Hinrich Foundation, Merle Hinrich, made his fortune facilitating trade between East and West, and believes individual relationships are still key to successful trade, even in the age of the digital economy.

“Developing a personal relationship post the advent of digital B2B [business to business] cross-border trade remains important,” he says, pointing to the continued growth of international trade shows in Hong Kong and China.

One of the earliest relationships built by the Americans was with the hong merchant Wu Bingjian, better known as Howqua. He was believed to have been the richest man in the world in the early 19th century, worth some US$25 million.

Howqua became friends with several of the early American merchants, who invited him to invest heavily in the US railway boom – the first example of Chinese foreign direct investment in a US infrastructure project.

At the time, China and Chinese goods represented everything luxurious, fashionable and exotic, and among the exquisite ceramics, silk and works of art on show at the museum are part of a dinner service ordered by America’s first president, George Washington.

As more American trading ships followed the lead of the Empress of China, with them were families who established trading houses in the factories of Canton, becoming extremely wealthy dynasties that went on to influence foreign policy with Beijing. The Forbes, Delano, Heard, Russell, Perkins and Astor families all became rich and powerful.

The wealth created was often reinvested in railways, real estate and factories, and much of the US’ growth into an economic superpower was seed-funded by China and Chinese trade.

Although it is easy to over romanticise the early days of the China-US relationship, the trade also caused environmental devastation, as land and sea were scoured for products that could be traded for Chinese tea, silk and ceramics. Sea otter populations were wiped out in the hunt for fur, and mature sandalwood trees are unknown of in Hawaii today.

Though less enthusiastic than their British counterparts, some American trading houses later sold opium illegally on the Chinese market, via rogue importers. Opium peddling was the West’s 19th century solution to the balance of payments deficit. It was the failure to find mutually acceptable trading arrangements that ultimately led to two opium wars fought between Britain and China – a situation the US and China managed to avoid.

The relationship was never perfect, but an examination of the early days of China-US trade in Canton reveals there was a genuine affinity and a willingness to establish mutually beneficial arrangements.

“I am not an economist or a diplomat but, as a historian I think there might be lessons to be learned from those early days of trade,” Chan says.

“The Dragon and the Eagle: American Traders in China, A Century of Trade from 1784 to 1900” runs until April 14, 2019 at Hong Kong Maritime Museum.