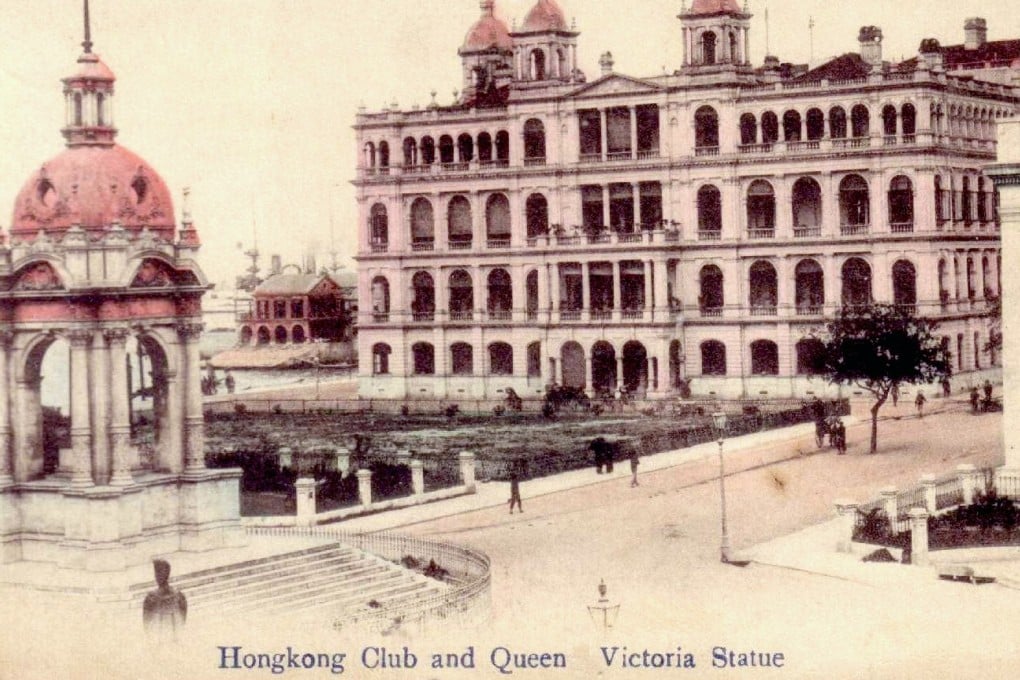

Hong Kong’s seat of power, Statue Square – its colonial history, symbolism, and how domestic helpers made it their own

- Built on reclaimed land at the turn of the 20th century, Statue Square met the need for a public place in which to bask in the glory of empire

- Once filled with statues of British monarchs and Hong Kong figures, it was a magnet for political rallies; today it is a gathering place for domestic helpers

The statues were waiting. Famed English sculptor George Edward Wade had painstakingly created bronze likenesses of Queen Alexandra and the Princess of Wales, and now they sat in Wharf’s godown, resting in the dark until their plinths were built.

“When completed the ceremony of unveiling both statues will be performed at the same time,” the Post reported on 9 July 1909. “Statue Square will then be well worthy of the name.”

From the beginning, Statue Square was meant to be a seat of authority – a place where all the most important institutions of Hong Kong came together. It was the culmination of a long, ambitious plan hatched by Catchick Paul Chater, the Calcutta-born Armenian entrepreneur who dominated economic and political life in Victorian-era Hong Kong.

In the late 19th century, Hong Kong was a booming entrepôt, but Chater realised it had little to show for it.

“Apart from its natural harbour, all the city had to send the world as an image of itself was a congested 3½ mile (5.6km) Queen’s Road and an elegant-looking seafront praya,” wrote French anthropologist Alain le Pichon in 2009. “It had no central square, no public place where its minimal government and its colonist community could celebrate their joint achievements, indulge in a symbolic display of patriotic fervour, and bask in the glory of belonging to what they believed was the greatest nation on earth.”