China promotes Xinjiang as tourist heaven while holding Muslim Uygurs in re-education camps

- Authorities in Xinjiang have created a parallel universe of smiling locals, exotic food and ‘ethnic’ dance, and are promoting the region to tourists

- Meanwhile, Turkic-speaking Muslims are subject to mass internment and tight security, and denied the right to cultural expression

From the expansive dunes of the Taklamakan Desert to the snow-capped peaks of Tianshan, Chinese authorities are selling troubled Xinjiang as a tourist idyll, welcoming travellers even as they send locals to internment camps.

The government has rounded up an estimated one million Uygurs and members of other mostly Muslim Turkic-speaking minorities into re-education camps in the tightly controlled region in China’s northwest, while creating a parallel universe for visitors, who are shown a carefully curated version of traditional customs and culture.

In the Old Town of Kashgar, an ancient Silk Road city, smiling food vendors serve mouthwatering lamb skewers while children play in the streets.

“It did not look to me like – unless you were picked up and put in a camp – that these Uygur communities seemed to be living in some kind of fear,” says William Lee, who has taught at universities in China for 10 years and visited the region in June. “That is just my impression,” he says.

Xinjiang, where flare-ups of inter-ethnic violence have led to unprecedented levels of surveillance, is one of the fastest growing areas for tourism in China.

Business has grown steadily over the years mainly because “Xinjiang is very stable”, explains Wu Yali, who runs a travel agency in the region. Though tourists are not used to the high level of security at first, “they adapt after a few days”, she says.

Travellers are barred from witnessing the most controversial part of Xinjiang’s security apparatus: the network of internment camps spread across the vast region.

Many of these facilities are outside main tourist hubs and are fenced off with razor-wired walls. China describes the facilities as “vocational education centres” where Turkic-speaking “trainees” learn Chinese and job skills.

“The violence that is being inflicted on the bodies of Uygur and other Muslim people … has been rendered invisible,” says Rachel Harris, who studies Uygur culture and music at the School of Oriental and African Studies University of London.

“For a tourist who goes and travels around a designated route, it all looks nice,” she says. “It’s all very quiet and that is because there’s a regime of terror being imposed on the local people.”

According to People’s Daily, the regional government offered travellers subsidies worth 500 yuan (US$73) each in 2014, after tourism plunged following a deadly knife attack blamed on Xinjiang separatists in southwest China.

By 2020, Xinjiang is aiming to hit a total of 300 million visits by tourists and earn US$87 billion from tourism, according to the region’s tourism bureau.

Many also offer “ethnic” experiences, often in the form of dance performances. Some tour operators include visits to Uygur homes.

What makes me sad is what ends up happening is there are only very specific parts of Uygur culture that get maintained because of the tourism

Even as Chinese authorities seek to contain the region’s Muslim minorities, they are monetising ethnic culture – albeit a simplified version of it, experts say.

“Uygur culture is being boiled down to just song and dance,” says Josh Summers, an American who lived in Xinjiang for more than a decade and wrote travel guides for the region.

“What makes me sad is what ends up happening is there are only very specific parts of Uygur culture that get maintained because of the tourism,” he says, citing the neglect of Uygur paper-making traditions and desert shrines.

Beijing’s security clampdown has also squeezed the artisanal knife trade in the city of Yengisar, says Summers.

“Ever since the management of Xinjiang became stricter, the impact on Yengisar’s small knives has been very large – now there are very few shops selling small knives,” says Li Qingwen, who runs a tourism business in Xinjiang.

The government wants Uygurs to “show how they excel in singing and dancing, instead of living under religious rules and restrictions”, he says. But while ethnic song and dance is showcased to tourists, Uygurs are often restricted in how they express their own culture.

For a tourist who goes and travels around a designated route, it all looks nice. It’s all very quiet and that is because there’s a regime of terror being imposed on the local people

Large, spontaneous gatherings of Uygurs – even if they involve dancing – are less frequent because of tightened security, says Summers.

Night markets too are more controlled. In Hotan, what used to be an outdoor night market is now inside a white tent, where red lanterns hang from the ceiling and uniform food stalls adorned with Chinese flags sell lamb skewers, but also sushi and seafood.

Over the past few years, cultural leaders in the Uygur community have disappeared, raising fears they have been detained.

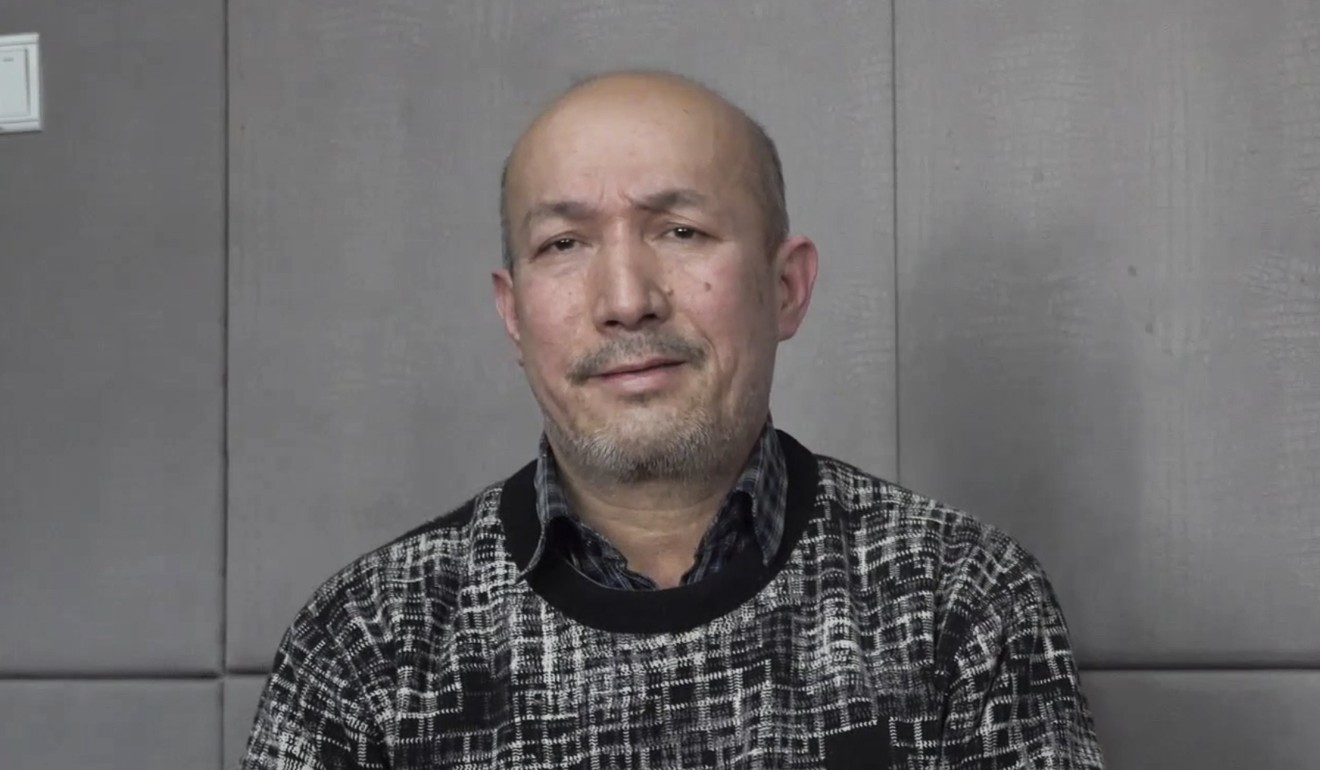

In February, Turkey’s foreign ministry claimed that prominent Uygur musician and poet Abdurehim Heyit had died in a Chinese prison – prompting China to release a “proof-of-life” video of an inmate who identified himself as Heyit.

Famous Uygur comedian Adil Mijit is also missing, according to social media posts by his son-in-law Arslan Hidayat.

Though tourists are buffered from the ugliest parts of Xinjiang’s security crackdown, it is not difficult to bump against the region’s many red lines.

A traveller from Southeast Asia, who requested anonymity due to fear of reprisals, describes the barriers he faced when trying to pray at a mosque.

Many places of worship were closed in Kashgar, he says, unlike mosques in other Chinese cities.

At Id Kah Mosque, Kashgar’s central mosque, the tourist was told he could not pray inside – and that he had to buy a ticket to enter.

“They want to separate travellers from locals,” he says, adding that his visit to Xinjiang confirmed what he had read about re-education camps. “There’s a lot more of Xinjiang that I want to discover. But I really hope that Xinjiang will become the old Xinjiang.”

.png?itok=arIb17P0)